Innovative program addresses mental health alongside career-tech ed

By Brenda Ortega

MEA Voice Editor

Several years into her career as an occupational therapist in Warren Woods Public Schools, MEA member Michele Morgan realized why her high school students didn’t always make an easy or successful transition from school to work.

It wasn’t a lack of technical skills holding them back — she had watched them master vocational tasks by breaking them down into manageable parts. Instead, she came to understand the profound impact of anxiety, trauma and depression on work readiness.

So like every great educator, Morgan set out to address that obstacle with students. The result — six years later — is a maker lab, a reset room, and an after school program which together combine vocational learning with proven mental health and emotional wellness practices.

“When you fuse the vocational training with mental health programming, it becomes its own unique product,” Morgan said. “When they’re making something, it’s usually a result of a values exploration we’ve had or a talk about whatever is holding them back. Maybe it’s unprocessed loss, grief, or anger never dealt with.

“We’re not psychotherapists; we start from where they are today, and we introduce six core processes of psychological flexibility. Then whatever they choose to make is a physical reminder or representation of the lesson that they can take with them to hold on to and remember.”

Sounds simple, but the results have been extraordinary, according to Ian Fredlund, an assistant principal who handles behavior referrals and discipline at the 1,200-student Tower High School.

Sounds simple, but the results have been extraordinary, according to Ian Fredlund, an assistant principal who handles behavior referrals and discipline at the 1,200-student Tower High School.

Attendance has gone up and behavior referrals down to near zero for every student who has participated in Morgan’s programming, he said.

But beyond the numbers data, Fredlund added, less tangible evidence points to how special her approach really is: “If I start gushing, I apologize — I can’t help it. I don’t usually talk like this about programs, but it’s really close to me and my heart.”

Mental health struggles among students in the U.S. have reached crisis proportions, the administrator said, adding he estimates that “30% of our students are struggling with suicidal ideation or thoughts of self-harm, and that number may be smaller than what it is in reality.”

Six years ago, Morgan started an after-school restorative discipline program involving mental health practices in a maker space for students who were skipping school or getting behavior referrals to attend voluntarily in lieu of detention or suspension.

Fredlund immediately began to offer students and families that alternative to traditional discipline where possible. Known as Scratch the Surface, the program has since become an after-school club because students who attended didn’t want to stop coming even after their time was up, he said.

“It was interesting because students would come back to me and say, ‘Well, I went. Do you want me to keep going?’ And I’d say, ‘That’s up to you. Do you want to keep going?’ And I’ve never had a student not want to go.”

Certain students’ successes in Scratch the Surface stand out, Fredlund said. One was a boy having outbursts in class because he didn’t know how to manage big emotions. “I referred him to Michele, and she helped him learn to express himself in ways that are appropriate and also constructive.”

Another was a student whose experience with trauma caused her to start skipping school and dropping out of activities she used to love. Now graduated by a few years, the girl not only stayed with the club through high school but also became a mentor to others coming in.

“I wish I could find the words to express what I know in my heart,” Fredlund said. “Without a doubt, her life was saved by this program. It’s hard not to get choked up thinking about it, and I know her mom would say the same thing: Without Scratch the Surface, I don’t think she would have made it through to adulthood.”

“I wish I could find the words to express what I know in my heart,” Fredlund said. “Without a doubt, her life was saved by this program. It’s hard not to get choked up thinking about it, and I know her mom would say the same thing: Without Scratch the Surface, I don’t think she would have made it through to adulthood.”

The Tower High School maker lab that Morgan has put together through fundraising, support from administrators, and grants includes lathes, a 3D printer, CNC router, laser engraver, woodburners, and sewing and commercial embroidery machines.

Students are able to make a huge variety of products, using many materials donated by kitchen and bath manufacturers. Students create functional art including granite memorial markers, turned wood and acrylic ink pens, engraved wood cutlery, mosaic art, textile art and fashions, candles, jewelry and more.

At the center of all of the technology, however, is learning about the brain and how students can manage negative thoughts and feelings. “I ask them to consider that the script they’re hearing in their mind is outdated,” Morgan said.

At the center of all of the technology, however, is learning about the brain and how students can manage negative thoughts and feelings. “I ask them to consider that the script they’re hearing in their mind is outdated,” Morgan said.

Based on Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT), Morgan’s curriculum helps students make space for uncomfortable feelings through mindfulness, cultivate self-compassion, and recognize that uncomfortable thoughts will pass by and do not represent their identity.

“Our curriculum teaches them that attempts to avoid, control or eliminate negative, anxious thoughts typically just exacerbates them, so trying to push things down has the opposite effect.”

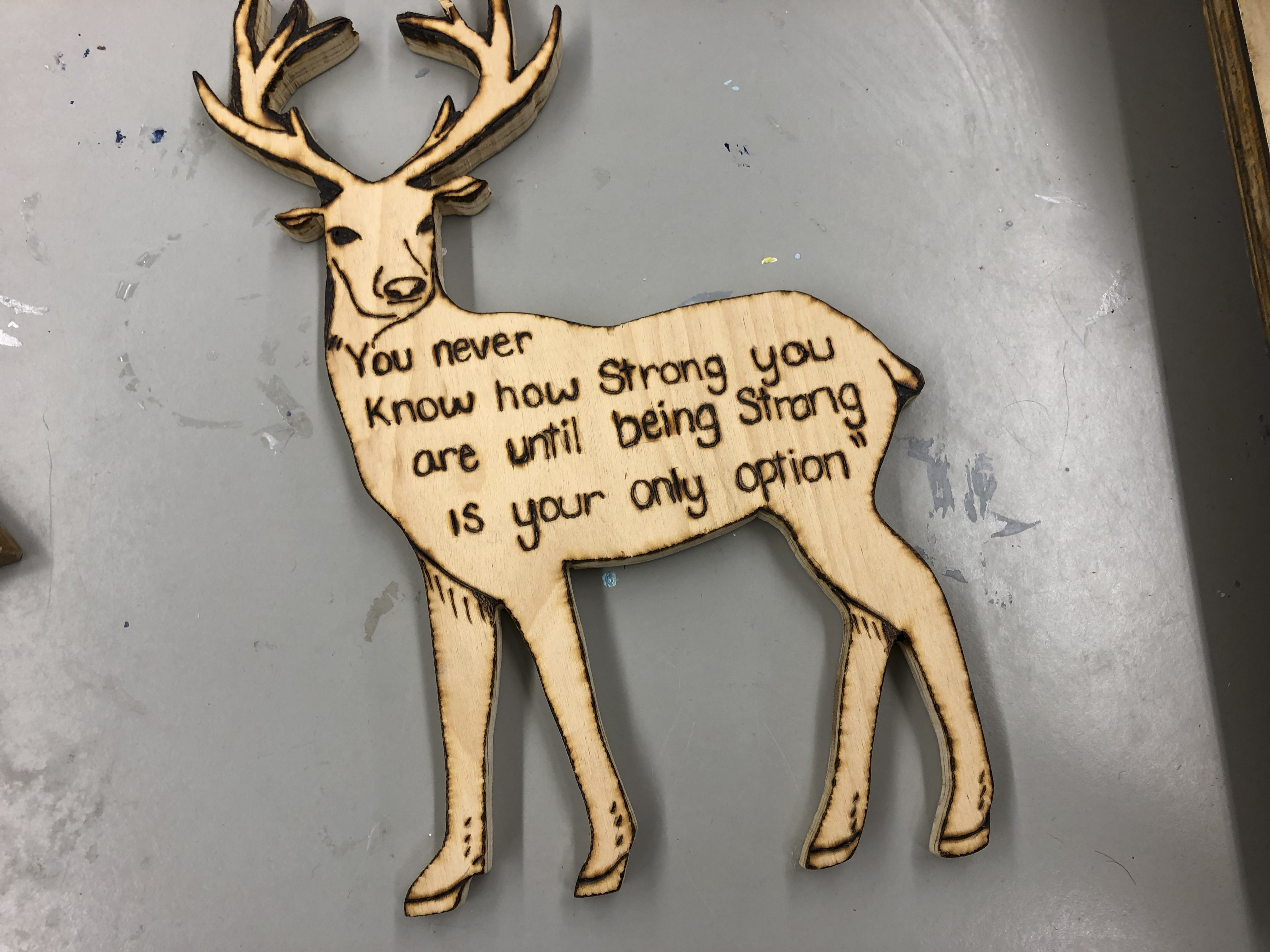

Any projects that students create then reflect their learning — typically in the form of pithy sayings and inspirational quotes but also metaphors to recall. One of the earliest lessons Morgan developed had students turn pens on a lathe and once finished to hold their pen tightly at first, and then loosely.

“We show them that whether you hold your pen tightly or lightly, it doesn’t fall, so why don’t you choose to hold your thoughts lightly? In other words, we ask them to consider, ‘I’m having the thought that I’m stupid.’ You aren’t the thought; you’re having the thought.”

When students hear that mental and emotional struggles are part of being human, that they won’t ever be “cured” but can learn to direct their actions in concert with their deepest values — instead of negative thoughts or feelings — “that’s something most of them have never heard before,” she added.

As an occupational therapist (OT), Morgan has a caseload of students at Tower, which houses a center-based program serving students with disabilities from 21 districts across Macomb County. She also is a transition coordinator assisting students’ preparation for and placement in work roles.

In addition to students on her caseload and the after-school Scratch the Surface program, Morgan has opened up her lab for use by resource room teachers to bring their classes on a weekly basis and for general education students to drop in for a quick “reset.”

Like a more elaborate reset room set up elsewhere in the building, Morgan’s lab space contains a swing and conveys gentle music, soft lighting, and other soothing sounds and smells.

Like a more elaborate reset room set up elsewhere in the building, Morgan’s lab space contains a swing and conveys gentle music, soft lighting, and other soothing sounds and smells.

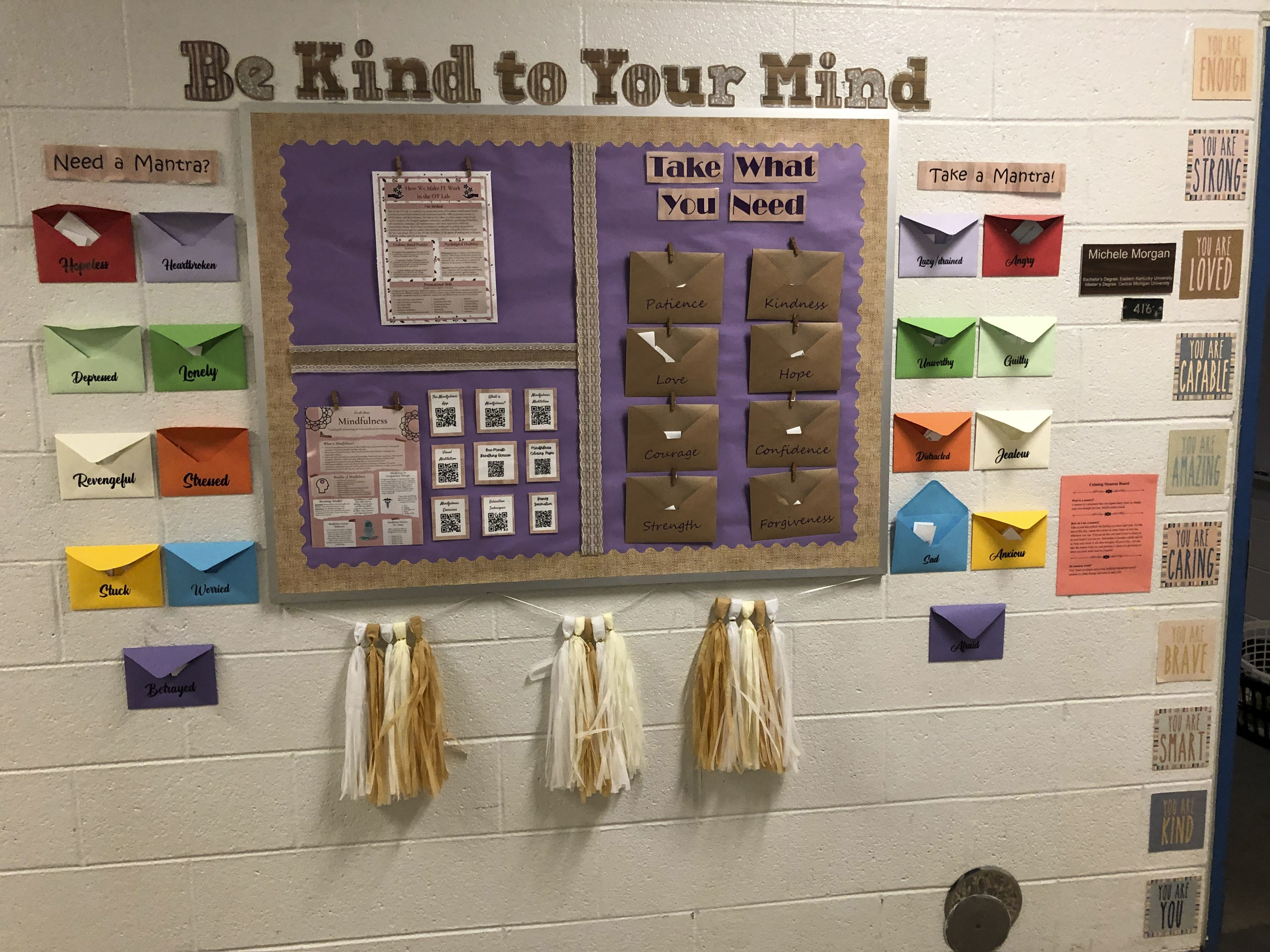

Students and staff alike can visit the wellness wall and choose from envelopes labeled with various emotions for an inspirational quote and QR codes directing them to mindfulness exercises.

“I can track and see which ones are most visited, and it’s this one,” she said, pointing. “Anxious.”

Along with making projects, students can choose from jobs to do in the lab, such as caring for the pet bunny or feeding food scraps from the culinary program to a commercial worm bin, which creates fertilizer for growing herbs that are donated back to the school’s student-run restaurant.

“The room is set up where something is always going on with jobs that can be constantly picked up and set down,” Morgan said. “For another example, we’re partnering with the local florist by volunteering to glue leaves together for homecoming corsages.

“And I don’t have to be the one implementing all the time — a paraprofessional can do this with a student who’s struggling, a teacher can come down with a class or group. I’m striving to create a system where jobs of the day are posted for students to choose and complete because it’s important that they can choose.”

Impressed with Morgan’s innovative approach to preparing students for work, local agencies Michigan Works and Michigan Rehabilitation Services support program costs and pay students an hourly wage for their participation during spring break and summer sessions.

Morgan is quick to point out she has not built the OT lab by herself. From the start, she has worked with interns from occupational therapy programs at Eastern Michigan University, Macomb Community College, and Wayne State University, who have supplemented her program by providing prospective practitioners. EMU provided seven months of graduate student research related to the program’s practices.

Neither does she solely operate the lab. Other adults in the building take ownership of the program’s goals too, she noted.

All of that teamwork has allowed her to expand into a second lab and after-school Scratch the Surface club at Enterprise High School, the district’s 110-student alternative high school. The lab at Enterprise is staffed for drop-in access during the school day with the help of college interns.

Enterprise Principal Timothy Baldwin said the OT lab has been invaluable in giving students an outlet and a release that they can choose when to visit in their day. “Kids learn through play when they’re little, and they learn through touch and hands-on as they get older, no matter what type of learner they are,” he said.

“Having that OT lab there is everything for a building like ours, because our students need to be able to just be sometimes. Most of the students that are here are low on credits for whatever reason — whether it’s some sort of anxiety or trauma they’ve experienced that got them off track.”

Offering students in alternative school the same expansive opportunities — like the OT lab — as in the larger Tower High School one mile away is important, Baldwin said.

“Now I feel kids are so much more open and willing to talk. And they’re taking some of those lessons that they learn here back home so their parents know this is a good place where they can reach out for help if they need it.”

The key to Morgan’s success is the focus on students’ health, welfare and happiness — not on grades or performance, agreed Tower High School’s Ian Fredlund. “It’s not only art or engraving or whatever they’re doing, it’s all the metacognition and reflecting they’re doing before and after,” he said.

“It’s all packaged in a way that’s fun and interesting, so I don’t even know that they’re aware of all the therapeutic processes they’re going through while expressing themselves. I just know we have severe mental health issues happening in high schools today, and this program is a resounding success. It’s saving lives, and holy cannoli — that’s powerful stuff.”

To connect with Michele Morgan, go to makeitworkprogram.com or email her at mmorgan@mywwps.org.