Educators celebrate power of mentorship through timeless story of James Earl Jones

By Brenda Ortega

MEA Voice Editor

At eight years old, Sid Halley learned his great-grandfather had mentored a young James Earl Jones to overcome a debilitating stutter and develop into a world-renowned and beloved actor – and he marveled that his mom’s grandpa taught Darth Vader of “Star Wars” fame.

As he grew up, Halley – an MEA-Retired former bus driver and local union president in Hillsdale schools who became the district’s transportation director two years ago – developed a more profound understanding of that relationship and respect for the act of mentoring which have deeply influenced his life.

“In the words of James Earl Jones, ‘A mentor is someone who guides a less capable person by building trust and modeling positive behavior,’” Halley said, speaking at the dedication of a new sculpture celebrating mentorship and the moving story of how his forebear, Donald Crouch, helped Jones find his now-famous voice.

“In the words of James Earl Jones, ‘A mentor is someone who guides a less capable person by building trust and modeling positive behavior,’” Halley said, speaking at the dedication of a new sculpture celebrating mentorship and the moving story of how his forebear, Donald Crouch, helped Jones find his now-famous voice.

The Oct. 14 ceremony at Kaleva Norman Dickson (KND) Schools drew nearly 300 people to the tiny community of Brethren, 35 miles east of Manistee, where Jones grew up and remained mostly mute from age four to 14 because of a severe stuttering problem.

“All of us have the ability to be a mentor, and I ask you to seize the opportunity when presented,” Halley said in his speech. “I believe that success in life is not measured by what we accumulate but by what we pass on.”

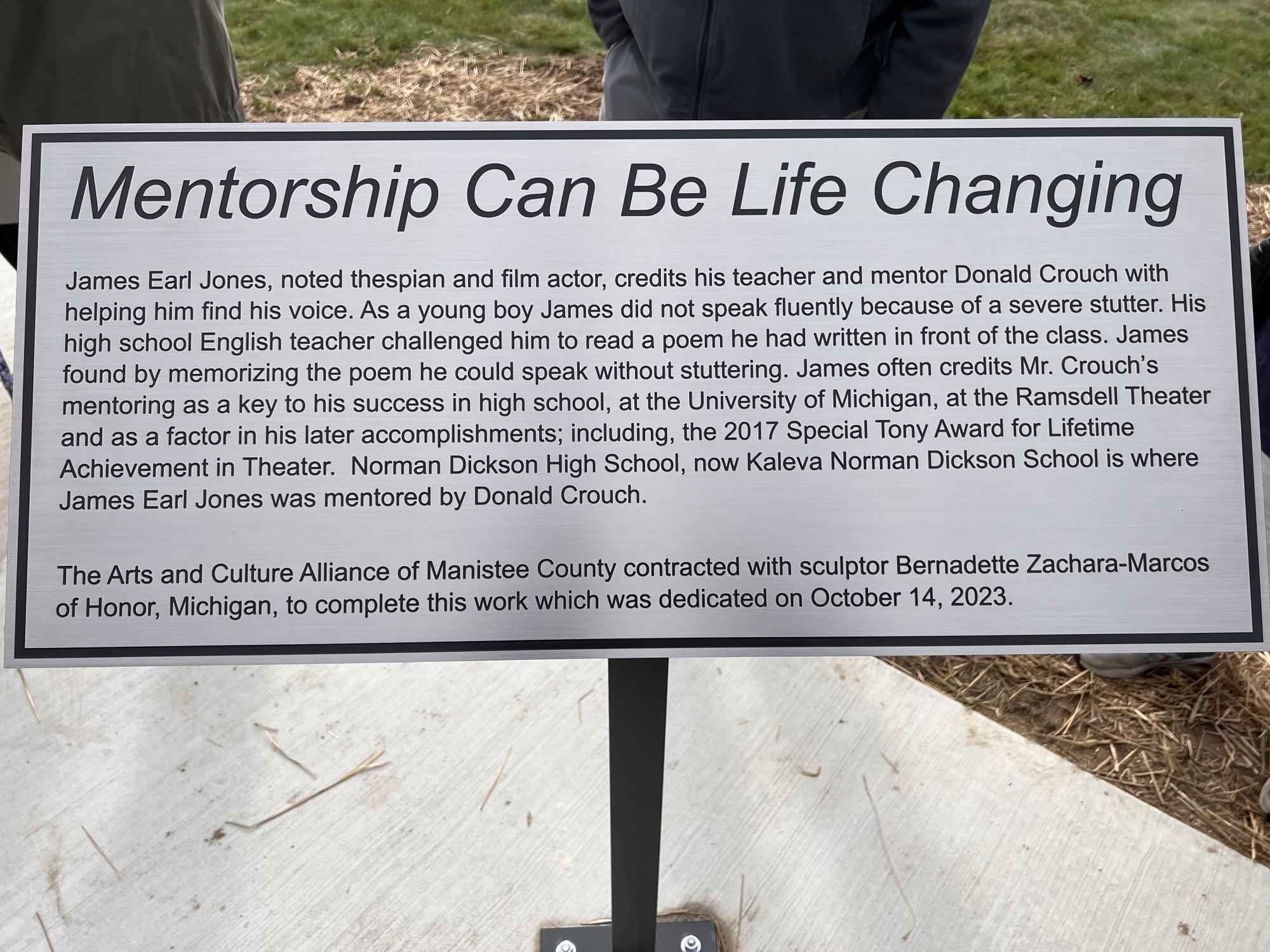

The ambitious sculpture project unveiled in the rural northwest Michigan community, titled “Mentorship can be life changing,” features two life-size bronze figures – each atop a round base made of concrete and granite – residing on a concrete pad in front of the school district campus.

The all-volunteer Arts & Culture Alliance of Manistee County led by a 10-member board – eight of whom are current or retired educators – raised more than $100,000 to memorialize the little-known story of how the teen who would become a legendary star known for his iconic rich baritone voice was first coaxed into public speaking by his teacher.

The sculpture depicts a pivotal moment – as Jones first recites a poem in Crouch’s English class – and “We had a special joy in bringing this project to our school,” said Cindy Asiala, vice president of the Alliance who is also a KND alum and MEA-Retired former Spanish teacher from the district.

The board didn’t realize how difficult it would be to raise that much money, Asiala said in an interview. But they were determined to honor Jones in the hometown area where he moved from Mississippi as a young boy with his grandparents, who had bought a 40-acre plot to subsistence-farm amid the Great Depression.

“We all took on important roles and were able to get things done, because of course most of us had years of experience as teachers,” Asiala said. “It was a real endeavor.”

Over 2½ years, the board spoke to groups, wrote press releases, ran concession stands at school events, and pieced together many small contributions from 170 donors. They received larger gifts from the Manistee County Community Foundation, Little River Band of Ottawa Indians, and 100 Women who Care Manistee County.

A fundraising idea of former KND history and government teacher and MEA-Retired member Judy Minton brought in more than 100 donors who wanted to include the name of their mentor in a bronze plaque next to the sculpture installation. A second plaque tells the story of Jones and Crouch.

Board members visited classrooms of teachers from various grade levels – MEA members Michael Phillips, Carol Rackow and Vivian Peck – so students could consider the importance of mentors, hear Jones’ story, and learn of the commissioned sculpture planned by noted Michigan artist Bernadette Zachara Marcos.

Based off of research the Alliance board gathered for the project, Marcos made the clay figures which were cast in bronze at a foundry and installed in front of the school.

In her speech at the dedication, Asiala shared what the students they visited said of mentors: “They named teachers, parents, friends, neighbors, siblings, grandparents. They said a mentor helps, teaches, guides, inspires, pushes, believes in you, is there for you, makes a person better.”

She also read sweet and thoughtful replies students gave when asked what the sculpture might mean to their community. One student said, “I think it will put us on the map and make us a popular spot,” Asiala said to gentle laughter in the crowd.

The Alliance is still trying to raise $5,000 to get over the finish line, as they borrowed that amount to keep the project on schedule, Asiala said. Donate here, or mail contributions to Arts and Culture Alliance of Manistee County; c/o Linda Cudney; 19708 Cadillac Highway; Copemish MI 49625

Now 92, Jones was not able to attend the sculpture’s dedication, but he sent a short recording that was played for those gathered. “My case was severe because I was a stutterer unable to carry on a conversation of any length,” Jones said in the recording.

Of his mentor, he said, “He built enough confidence for me to finish high school and go on to the University of Michigan with a full scholarship. I would like to keep this simple, but there is nothing simple about Professor Crouch.”

Over the years, Jones has spoken and written about his mentor and the importance of those like him who take the time to be “dependable, engaged, authentic and tuned into the needs of the student,” as he described the role of a mentor in his recording.

Crouch was a Mennonite minister, professor, and colleague of poet Robert Frost who taught at several Midwestern colleges before retiring to his farm in Manistee County. He soon found he missed teaching, so he left behind the plow and took a job at Dickson High School in Brethren.

“Professor Crouch discovered that I wrote poetry, a secret I was not anxious to divulge, being a typical high school boy,” Jones wrote in an anthology published in 2011, The Person Who Changed My life: Prominent Americans Recall Their Mentors. “After learning this, he questioned me about why, if I loved words so much, couldn’t I say them out loud?”

One poem that Jones wrote captured Crouch’s attention, titled “Ode to a Winter Grapefruit.” In the Depression, the federal government’s Works Progress Administration (WPA) delivered Florida citrus fruit north in winter to prevent rickets and scurvy caused by vitamin deficiency, he told M-Live in 2014.

“It had a vitamin in it that they knew we needed, so part of the WPA project was dropping off crates of grapefruit by train all along the rail path,” Jones said. “My family would get a crate, and I just thought it was the most wonderful food in the world, and I wrote an ode to grapefruit.”

Although he no longer remembers the full poem, Jones said it was written in iambic tetrameter like the epic poem “The Song of Hiawatha” by Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, as in its last line, “and-my-bel-ly-full-of-grape-fruit,” which he recalled in a June 2005 Time magazine piece, titled “Finding My Voice.”

When Jones showed it to his teacher, Crouch replied, “‘Jim, this poem is too good for you to have written. To prove you wrote it, get up in front of the class and say it by heart, out loud,’” Jones said. “And I did. I wanted to prove that I wasn’t a plagiarist!”

Once he got through the poem without stuttering, “from then on I had to write more, and speak more,” Jones wrote in The Person Who Changed My Life. Crouch encouraged him to compete in debates and oratorical contests. “This had a tremendous effect on me, and my confidence grew as I learned to express myself comfortably out loud,” Jones said.

“On the last day of school we had our final class outside on the lawn, and Professor Crouch presented me with a gift – a copy of Ralph Waldo Emerson’s Self-Reliance. This was invaluable to me because it summed up what he had taught me – self-reliance. His influence on me was so basic that it extended to all areas of my life. He is the reason I became an actor.”

Considered one of the greatest actors of all time, Jones is among the few entertainers to win the EGOT (Emmy, Grammy, Oscar, Tony) with three Tony Awards, two Emmys, and a Grammy. He received an Honorary Academy Award for Lifetime Achievement in 2011, among many career honors.

He is best known for movie roles, such as leader of the Dark Side in the Star Wars saga, Mufasa in The Lion King, and Terrence Mann in Field of Dreams. But Jones is also a giant of American theater.

He said in 2005 that he remained a stutterer throughout his long career and continued the practice of reciting poetry to overcome it. “I still read the Dylan Thomas poem ‘Do Not Go Gentle into That Good Night’ every night before I go onstage,” he said back then. “I know it by heart now.”

Several members of Jones’ extended family attended the dedication ceremony, including cousin Terry Connolly who said in a speech that Jones himself acted as a mentor in his life.

“There’s times when I would feel down and I could always call him and we could talk and he’d lift my spirits and I could keep going,” he said. “It was his indomitable spirit to succeed in acting that kept me going to succeed.”

Meanwhile, KND Superintendent Jakob Veith lifted up educators in his talk about about the power of mentors. “To our teachers and staff, I cannot think of another profession where you have the power to inspire so many,” Veith said.

“You have one of the hardest jobs in the world and sometimes the most frustrating. At times you may wonder why you keep sacrificing so much time and dedication to the profession. Today is a reminder of why you do it. Today is a celebration of your sacrifice, your leadership and your mentorship.”

Similar sentiments sum up why Sid Halley attended the dedication of a sculpture for a great-grandfather he never met. It was a beautiful reminder of his good fortune growing up in a much larger community in suburban Detroit – Wayne-Westland – the son of two teachers, he said afterward.

Halley said he had guidance in his youth from many adults who knew his father, the local union president. Later he married wife Mary – also an educator – and the couple enjoyed mentoring young people in Jonesville, the small community where they’ve raised a family, he added.

“Our home, especially our dining room table, is never empty,” Halley said. “Most of the youth in our area know our door is always open, a seat at dinner is always available, and a good discussion will always be had.”