Facts v Fallacy

PART I: School Performance

By Brenda Ortega

MEA Voice Editor

MEA Labor Economist Tanner Delpier tells stories with data. The tale he tells of public education in Michigan runs counter to the message heard far too often in sound bites on the news.

We continually hear that public schools are “failing,” despite “record” state funding, because educators lack “accountability.”

“None of that is true,” Delpier says.

Yet former Michigan Gov. Rick Snyder announced last June he plans to spend his time and millions of dollars to pound the message of school failure into voters’ minds between now and the next statewide elections in November 2026.

This is the same Rick Snyder who presided over a steep, years-long decline in the state education budget, which hit bottom under his leadership in 2013. At the time, the goal of Snyder and others was shifting dwindling public resources to private, religious and for‑profit charter schools — something we must remain vigilant against.

Pundits and influencers who want to perpetuate falsehoods know if they repeat a lie often enough, then eventually people will believe it. Here is the truth.

Our schools are not failing, though educators face significant challenges.

Education funding in Michigan still has not returned to peak levels reached in the early 2000s.

Accountability has been the focus ever since President George W. Bush made standardized test scores both the goal and the yardstick in 2002.

Framework

The education statistic most tossed-about lately is a ranking of Michigan compared to other states in the National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP) — often referred to as The Nation’s Report Card.

Within this framework, the state ranked 44th among states in fourth-grade reading scores in 2024.

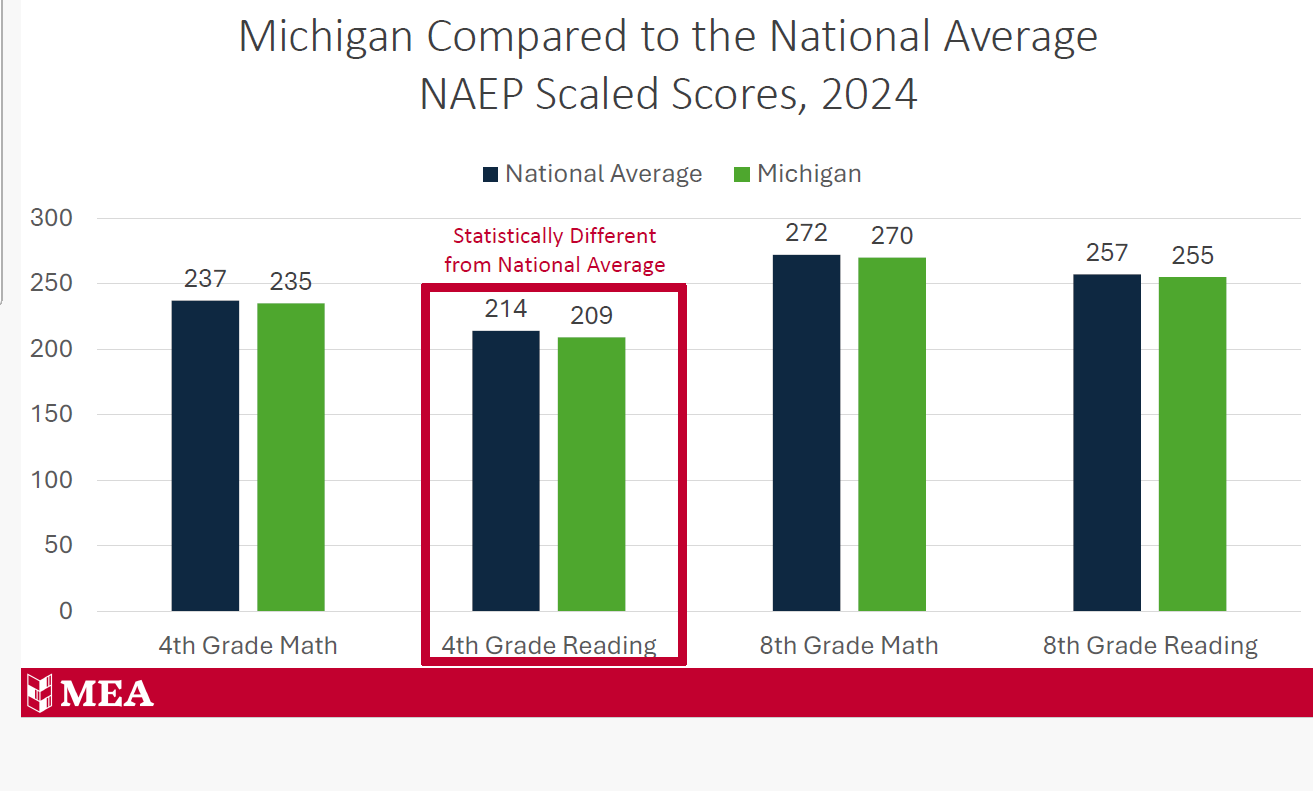

Michigan students performed at the national average on three of four NAEP measures that year except fourth-grade reading, which fell below average. Because the NAEP only tests a small random sample of students from each state, the standard error rate centers at 1.5 points, Delpier said. [FIG. 1]

Score differences within the margin of error are not statistically meaningful, but news media and politicians use them to rank states and speculate about causes — even though the maker of the assessment (the National Center for Education Statistics or NCES) cautions against it.

In the case of fourth-grade reading, 31 states scored higher than Michigan which was statistically tied with 18 other states. In general, NAEP scores are tightly distributed — meaning a tiny increase can move up a state by many places in the rankings, Delpier notes. [FIG. 2]

Certainly there is room to improve “average” scores, but it’s inaccurate to depict student performance that is mostly on par with other states as a dire crisis unique to Michigan. What’s more, improved math scores in Michigan and the nation in 2022 and 2024 garnered little attention.

“There’s an asymmetry to how scores are discussed in the media which has little to do with the actual learning that’s happening in schools and more to do with incendiary headlines that grab attention or try to place blame,” Delpier said.

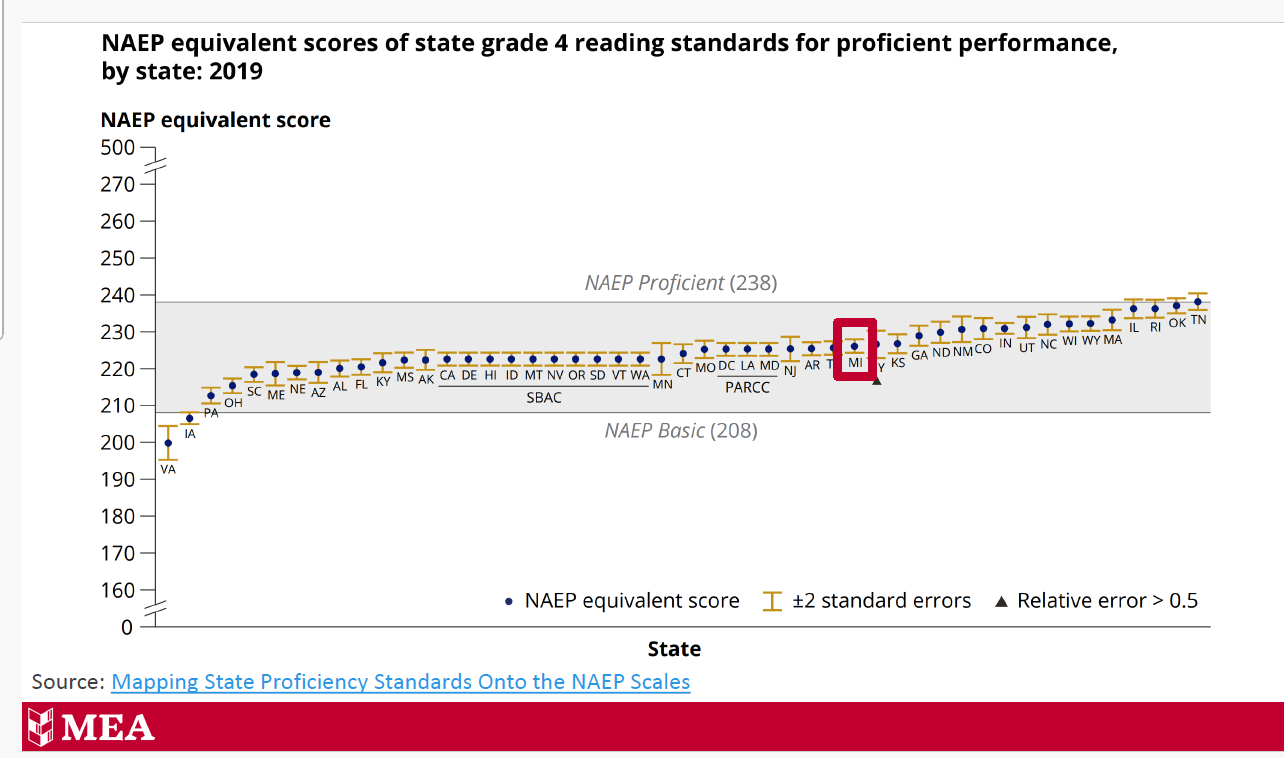

Another way in which NAEP scores have been twisted to fit a political message is in the definition of “proficient.” In NAEP terms, proficient is a high bar and does not correlate to grade-level achievement.

Nevertheless, both news outlets and politicians from both parties misinterpret NAEP fourth-grade reading scores, for example, to say that only 25% of Michigan students are reading at “grade level” because that is the figure reported as reaching “At or Above Proficient.”

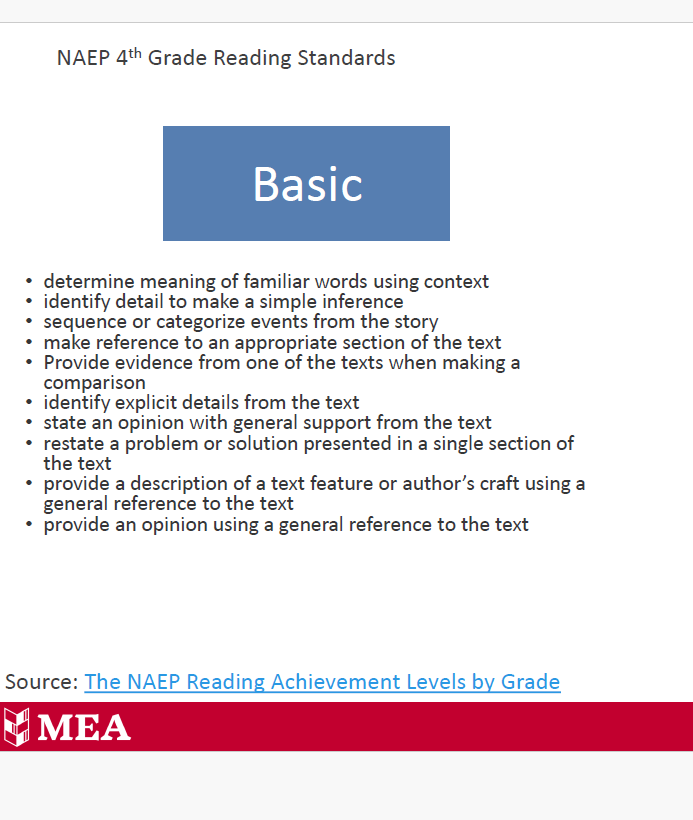

In fact, all but two states set their individual proficiency standards lower than the national test does — closer to the NAEP’s “Basic” standard, Delpier said, noting: “If you read the (NAEP) definition of ‘Basic,’ it involves pretty sophisticated reading skills.” [FIG. 3]

In Michigan, 55% reached “At or Above Basic” level compared to 59% nationally. “That’s not where we want to be as a state or as a country, but it’s better achievement than what is being reported,” Delpier said.

Instead of ranking states in a competition, the NCES recommends more broadly examining scores over time and breaking down data by subgroups — also combining the data with other information — to inform policy and instructional improvements.

The fact is nationwide scores remain below pre-pandemic levels in all tested grades and subjects, according to an NCES analysis. Moreover, the gap between the highest- and lowest-performing students is large and growing across the country — a trend seen for more than a decade.

The NCES analysis asked and answered a key question: “Just how big is this gap? On a 500-point scale, the lowest-performing students generally scored about 100 points below the highest-performing students in 2024.”

Challenges

According to the 2025 Kids Count in Michigan Data Book & Profiles, which released the latest information on child well-being in September, nearly one-in-five Michigan children were living in poverty, and food insecurity was on the rise in 61 counties.

“Many families in Michigan are still struggling to make ends meet on a daily basis, which will only be exacerbated by recent federal cuts to social safety net programs,” a summary of the report’s findings noted.

The Kids Count Data Book provides an evidence-based list of policy proposals to boost child well-being for state leaders to consider, including a few education-related proposals:

- Fully fund access to early childhood care and education

- Improve access to mental health services in public schools

- Increase resources to schools and students with higher needs

- Adopt universal free community college

One of the struggles for educators is the expectation that they can solve all of society’s problems without proper resources or training, says MEA member Amy Urbanowski-Nowak, an English teacher in Birch Run and president of the local union.

“I can’t solve students’ anxiety and depression, address special education needs, establish relationships, and teach English all at the same time,” Urbanowski-Nowak said. “Teachers feel like the weight of the world is on their shoulders.”

(Read more of Amy’s thoughts about this topic in a related column.)

Meanwhile, Dick and Betsy DeVos have launched a new nonprofit organization, the Michigan Forward Network, to push their longstanding anti-public education messages.

Over the years, the DeVos family has spent millions of dollars funding right-wing political candidates and causes, including school voucher schemes.

According to Bridge Michigan, the DeVoses’ new group will operate as a 501(c)(4) — a “dark money” nonprofit that will not have to disclose its donors and can spend unlimited amounts to influence elections but cannot directly coordinate with candidates or campaigns.

That is a big part of the problem faced by Michigan schools, says Steven Norton, a public policy analyst and executive director of Michigan Parents for Schools, a nonprofit advocacy group working to support community-governed schools in the state.

“Over the last two decades, Michigan public schools have suffered a blizzard of ideologically driven ‘reform’ attempts,” Norton wrote in a recent op-ed in Bridge. “Nearly all of these focused on punishing what the sponsors saw as ‘failure’ and reshaping schools to fit their ideologies favoring privatization.

“They were not designed to help our local public schools, but to drive parents to other alternatives, weakening public schools in the process. How can we possibly be surprised at the result?”

Watch for the rest of our three-part Fact v Fallacy series in upcoming issues of MEA Voice, including “School Funding” in February-March and “School Policy” in April-May.

Then stay tuned for a retrospective on the legacy of the Snyder years in the August-September edition.