Harmed by Historic Flooding, Helped by Union Family

By Brenda Ortega

MEA Voice Editor

Surreal. Overwhelming. Indescribable.

Talk to MEA members in Midland, Saginaw, and surrounding counties, and you’ll hear those words used repeatedly to try to convey the effects of a 500-year flood event in May which displaced thousands of people and cut a wide swath of destruction through the huge mid-Michigan river valley.

They use those same words again to describe the help that arrived from their union and school families – roving work crews, meal deliveries, donations of supplies.

“It’s indescribable because you just feel it in your heart,” said MEA member Jill Bischer, a speech and language pathologist in Midland schools who evacuated her home of 26 years shortly before floodwaters broke two area dams.

“You try to thank people, but words aren’t enough. Hugs aren’t enough.”

Sitting on a slope at the high end of Carroll Creek, Bischer’s home is not in a floodplain and has never taken on water before, she said. Since the torrent of floodwater coursed through her property on May 19 and 20, two of the walls in her basement collapsed after filling with nine feet of water and mud.

The rushing waters thrashed heavy items – including large exercise equipment – from one end of the basement to another. Important mementos and personal items stored in bins, such as her 19-year-old son’s diploma, awards, cap and gown – “almost everything” – was lost.

“We maybe saved a couple of things from down there, like 1 percent,” she added.

Crews of helpers – teacher colleagues and their spouses, among others – showed up with food and equipment, including large tents to set up for shade in the yard, to haul out belongings from other parts of the house that needed cleanup.

“They just took over,” Bischer said. “They said, ‘You don’t worry about anything. We’re moving forward,’ and they were itching to get in.”

A photography buff, Bischer had written off boxes of wet and muddy pictures as trash, but her helpers – knowing the importance of her hobby – dipped the prints in distilled water and laid them out on dozens of sheets spread on the lawn for drying things.

“You go on autopilot and try to take one day at a time, one hour at a time, but it’s easier when you have such loving and caring colleagues and friends to help,” she said. “It’s just amazing – they probably saved most of my pictures.”

Bischer is one of several dozen MEA members harmed by the historic flooding who have begun a long recovery process – many without flood insurance coverage to help with the costs of rebuilding.

MEA has launched a GoFundMe page to help members who suffered uncovered losses in several mid-Michigan counties. Donate today to help us reach our goal of $25,000 in assistance—we’re already more than halfway there!

The flooding that led to the catastrophic collapse of Edenville and Sanford dams – which drained Wixom and Sanford lakes and unleashed a torrent of water on communities downstream – resulted from spring rains fed by moisture from a distant tropical storm.

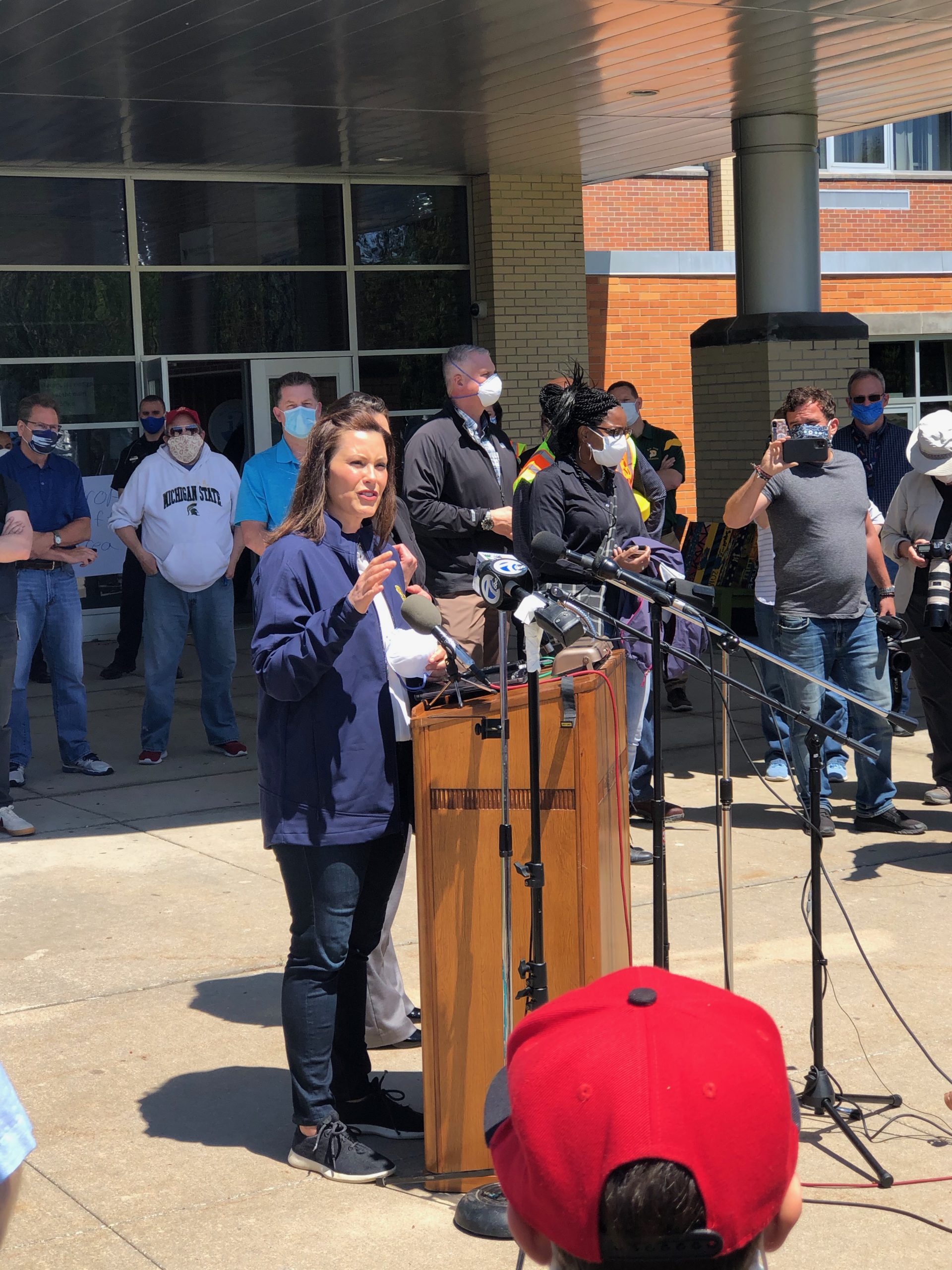

The heaviest downpours occurred on Monday, May 18, in rural regions north of Midland: Iosco, Gladwin, and Arenac counties – which were included in Gov. Gretchen Whitmer’s flood disaster declaration but have received less attention than more heavily populated areas where the water flowed and dams broke.

MEA member Tiffany Bischoff lives just outside of Tawas City, 60 miles north of Midland, where 8 inches of rain caused a pressure buildup against her basement walls. Her house, built on a hill with a drainage tile around the perimeter, has never flooded before, she said.

“Two of our basement walls cracked and bowed in, causing water to flow in through the cracks. We pushed water to the sump pump for nearly 20 hours, and it could not keep up.”

With her house now supported by braces, jacks, and beams on two sides, Bischoff’s insurance company has denied her damage claim because she did not have flood insurance. The initial estimate for repairs stands at $50,000.

Bischoff has been working with Iosco County commissioners, supplying estimates, pictures and information to support the area being deemed a federal disaster area, which could bring some help in the form of loans and grants for rebuilding.

“It’s extremely overwhelming and stressful all while trying to deal with teaching from home and all of the changes happening with the recent COVID-19 pandemic,” she said.

Suddenly the pandemic took a backseat to more immediate concerns, said paraeducator Rhonda Sturgeon, president of the support staff union in Meridian Public Schools. The district is located in Sanford, a small community devastated by the collapse of Sanford dam.

“The next day, everything was underwater and the rain was still coming down,” Sturgeon said. “By Thursday, the town was completely wiped out. Every business was affected.”

While Sturgeon’s own house near Sanford Lake was untouched, she immediately got on the phone to figure out how many of her members and students were hit by the devastation. “One of my parapros, her whole house was washed away off of Wixom Lake. She has nothing.”

The local president got in touch with MEA UniServ Director Renaye Baker, who scrambled to get some immediate help to those facing the most drastic harm. The next day, Sturgeon spent six hours handing out meals and water at her school.

She had to pick her way around washed-out roads and bridges to get there. “To keep going, you have to compartmentalize,” she said. “When I drive through Sanford, I just cry. It’s surreal—like those movies you see where it’s complete devastation.”

By Sunday, Sturgeon was driving around helping to deliver grilled chicken meals prepared by a teacher friend and her husband for folks doing the difficult cleanup work all over town.

“Seeing people coming together as a community, it was special,” she said. “They didn’t care if you were black, white, brown, Republican, Democrat. If you were old and couldn’t do physical work, you could sit here and check people in. If you’re a kid, then you hand out water. Everybody had a job.”

Besides handing out meals, Sturgeon also helped her teacher friend – MEA member Sarah Larges – develop an idea for selling a “Sanford strong” t-shirt to benefit the Meridian school district’s relief fund for families hurt by the flood.

Larges normally makes t-shirts as part of a “side hustle” that also includes artwork made from antique windows, so it wasn’t too much of a stretch to design a shirt to sell at $20 each and set up online ordering.

As a 20-year English teacher and longtime track coach in Sanford, Larges had many connections to get the word out. Still, she didn’t expect to sell close to 1,000 shirts in a few days.

With limited equipment for making the shirts, Larges said she reached out for help from a community partner that came through. Sandlot Sports, which supplies uniforms for many tri-county sports teams, offered to print the shirts at cost for which “I was just beyond blessed and thankful,” she said.

Larges and her family experienced flooding in their yard, but their home on a hill was spared while many neighbors suffered damage. Part of her felt guilty for escaping harm while others are struggling, but another part of her focused on finding ways to help.

“Securing funds so my students’ basic needs are met – that’s my wheelhouse,” Larges said. “I’ve always been a major advocate when we do other programs at school, such as Christmastime or adopt-a-family, and I just really work to make sure those needs are met.

“That’s why I’m doing it. This money is going to benefit kids and families in my community. I love them, and I tell them I do. They know I love them.”

The devastation that so many families in Sanford have endured led MEA member Jolynn Lippie to create a Facebook page to reunite people with a huge variety of items lost in the floods – from vehicles to furniture to photographs, and her story was featured on the local television station.

Similarly in nearby Swan Valley School District in Saginaw County, the local union has been finding and organizing donations of items for families in need after the floods, said Gina Wilson, president of the local education association.

Efforts have also involved members helping members by cleaning out homes, donating money and supplies, and housing colleagues who evacuated or lost homes. “We’ve had several members affected by the flood, and our community as a whole is experiencing a vast amount of devastation,” Wilson said.

In Midland, where the high school was used as an emergency shelter, the local president received a call for help from the superintendent who was left shorthanded by a lack of Red Cross volunteers amid the pandemic.

“I emailed my members and said, ‘Anybody that can come to Midland High to help, let’s go,’” Midland City EA President Mark Hackbarth said. “And then my wife and I went over there and did what we could all day. Most of the people there were elderly – evacuated from a senior living facility right on the river in downtown Midland.”

The next day and for days after, Hackbarth coordinated volunteers by setting up and monitoring a Google form where members could ask for help and another where members could offer donations and services.

One-quarter of the town was flooded and 30 members from his local suffered damage, Hackbarth said, “ranging from flooded basements, to basement walls collapsing, to losing a cottage that was on one of the lakes, to having a home condemned. It’s a big range in terms of what we’ve lost.”

When a member needed help clearing debris, Hackbarth joined forces with a teacher colleague and showed up with other roving demolition teams. Debris piles awaiting pickup at curbside stood as tall as the houses in neighborhoods across the city.

“We were hauling out wet carpet and tearing down drywall, all sorts of stuff,” he said. “We did six houses in five days.”

In addition, while educators had already been doing the difficult work of remote teaching and learning, now they had to try to touch base with students amid a global pandemic and 500-year flood, the 29-year middle school science teacher said.

“It’s pretty much indescribable. We’re reaching out to students to see if they’re OK, do they need anything? And I don’t know if anyone has had time to process it yet. It’s not close to anything I’ve ever had to deal with as a teacher—not even close.”

One of the houses where Hackbarth helped to tear out floors destroyed by floodwaters belonged to MEA member Tonya Lambert, a middle school English teacher who was making dinner when evacuation orders were announced for her area. She had 15 minutes to grab clothes and get out.

Lambert lives in a quad-level home where three of the four floors were damaged by water. A neighbor kayaked into the area the next day and shared photos of the scene to Lambert’s shock. Then it was time to get to work, she said.

“There were moments of tears, and moments of ‘We can do this,’ and then there were moments of ‘Well, this has to get done.’ Somehow you find energy you didn’t know you had.”

Up to 20 teachers and spouses showed up over the next few days to haul out furniture and appliances, among other hard work, she said.

“My union president actually tore up my beautiful cherry wood kitchen floor. My coworkers and their spouses – some I’d never met – were tearing up carpet, pulling out drywall. It was dirty, filthy, grueling, unpleasant work, and they did it for hours on end.”

A teacher friend from her building housed Lambert and her husband for a while, and a gift card from MEA helped buy some groceries. “It’s been quite a year,” she said.

Indeed, the first half of 2020 has presented unprecedented challenges, and it’s good to have a union family in these times, said Jerry Lombardo, chair of the 12-B Coordinating Council, which includes Midland, Meridian, and several other districts.

Local union leaders and staff have helped to work out agreements and deal with problems arising from the sudden shift to remote learning forced by the pandemic, and they’ve coordinated financial and manpower donations to members in need from a rarely-before-seen flood event.

“It’s been amazing to see all the different ways that members are helping their colleagues,” said Lombardo, a middle school special education teacher. “I think that’s been the biggest thing about the union through all of this—it allows people to feel they’re not alone.”

Help MEA members affected by the flooding—Give to the MEA support fund today.