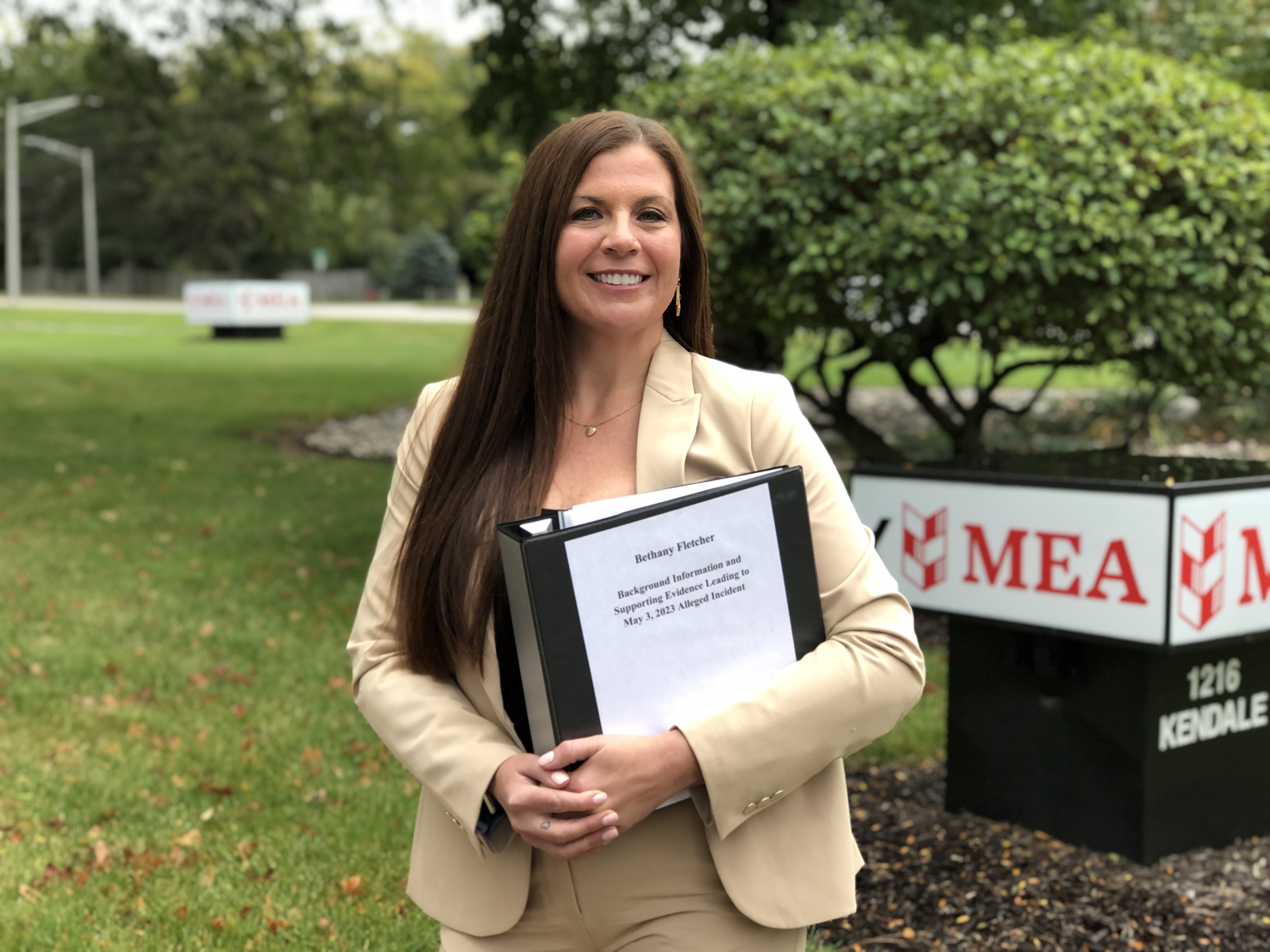

Unfairly targeted, educator wins large settlement

Growing up in the mid-Michigan town of Ithaca, Bethany Fletcher enjoyed small-town life and learning from great teachers in close-knit schools. She dreamed of becoming an educator and returning to work and raise a family in her hometown – and that wish came true.

An MEA member over the past 13 years, Fletcher was teaching seventh- and eighth-grade history at the junior-senior high school in Ithaca, 25 miles south of Mt. Pleasant, where she also coached the middle school cross country team. She and her husband have three young children.

School felt like home and family: colleagues were once her teachers, and she used to babysit for the principal’s kids. “This was 100% my dream job, and I thought I would be there forever,” Fletcher said.

She consistently earned the highest ratings on her evaluations and stepped up to leadership roles. She served on the school improvement team, wrote presentations on school improvement plans, mentored new teachers, volunteered to be middle school representative on the faculty council.

When she started to be mistreated at work, Fletcher didn’t know her rights and the law. But she maintained teaching excellence while documenting what was happening – and for that she’s grateful.

“I have no idea how I managed any of it, but I would say to anyone facing harassment as I was: your best protection is to report everything. Then keep track of every email and text. Record every instance you might need to reference in the future. Maybe you won’t need it, but if you do – it’s there.”

Fletcher needed it. Last spring the district tried to fire her after what she termed a years-long “cycle of toxicity and harassment.” She fought the district’s tenure charges with MEA legal representation and won the largest sum awarded in a union-led settlement in more than 20 years.

Beyond that, she also regained strength from a low point when she didn’t know how to go on, Fletcher said: “What happened to me was unimaginable. It’s hard to put into words the damage that was done.”

Her concern was first raised in 2021 after she told the principal a coach had made a vulgar sexual comment to her at a golf-outing fundraiser, and no discipline occurred. Soon another coach texted offensive sexual remarks to her and another female staff member, and again no serious repercussions followed her reporting.

In the wake of those reports, Fletcher said she sensed a negative new dynamic between her and an administrator who was a former longtime coach whose success in athletics was celebrated in the town.

From that point the sexual harassment moved on to multiple instances of students making inappropriate comments to her and receiving little or no punishment from administration, including one boy who mimicked a viral trend from social media by asking Fletcher about her genitalia during class.

Last school year, a group of students claimed Fletcher had exposed herself in class. She was disciplined before the students came forward to admit it never happened. The discipline was rescinded.

Then in May, two girls who had a friend’s cell phone alleged that Fletcher had sent an inappropriate photo of herself to a male student in a social media platform that deletes shared images after a time.

The next day, without warning, Fletcher was escorted to the superintendent’s office, told of the allegation, informed it had been investigated, placed on paid administrative leave, and ordered to leave the building. In shock, she quoted a favorite saying of the principal on her way out that day, she said.

“I said, ‘What’s right is right. What’s wrong is wrong.’ I did not do this.”

The district based its actions on the students’ claims and drawings that administrators asked them to make of the supposed photo, said MEA UniServ Director Lisa Robbins. Fletcher was not interviewed, and neither her phone nor the student’s phone was examined despite her offer, Robbins said.

When the district soon began to seek tenure charges, Fletcher was “extremely fragile,” Robbins said. “I don’t know how else to describe it. She couldn’t even drive herself to the office to discuss the case.”

After two years of dealing with sexual harassment, and then facing dismissal, Fletcher had reached a breaking point and didn’t want to work at the district anymore. But she wasn’t willing to acknowledge misconduct that didn’t happen.

Meanwhile, the district refused to negotiate a settlement despite their only evidence being “stick-figure sketches” from students, Robbins said. “I repeatedly tried to warn them they didn’t have a case.”

The problem is school administrators have been emboldened by changes to teacher tenure law made in 2011 under Gov. Rick Snyder, which lowered the bar for firing teachers from requiring “just cause” to allowing decisions that are merely “not arbitrary and capricious,” said MEA Attorney Doug Wilcox.

Wilcox advised Fletcher to appeal the district’s tenure charges. That is when Erin Hopper Donahue, an attorney with the White Schneider firm, was contracted by MEA to handle the case. That moment is also when Fletcher said she hit bottom.

“I hate saying this part out loud,” she said in a voice shaking with emotion. “When I first met with Erin, I had decided if I didn’t think she believed me, I didn’t want to be alive anymore. Because I couldn’t imagine my life without being part of that community.”

Instead, in telling her story and documenting details with a binder of evidence Hopper Donahue asked her to compile, Fletcher got reassured what happened to her was wrong. She had experienced sexual harassment. The district should have conducted a Title IX investigation long ago.

“I learned Title IX is supposed to protect not only students, but also educators, from sexual harassment. And for the first time I thought, Gosh – maybe it’ll be OK.”

Hopper Donahue filed a complaint with the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC) charging sex discrimination and retaliation. In July, trial began on the district’s tenure charges with the district presenting its case on the first day of what should have been a three-day hearing.

It quickly became clear from an official’s testimony that investigatory notes had been withheld which should have been turned over to Hopper Donahue as requested during the discovery phase. On those grounds, the lawyer got the case thrown out on the first day – an exceedingly rare event, she said.

By then she’d seen the district’s case and cross-examined student witnesses who said they saw a photo of Fletcher but couldn’t produce a copy despite knowing how to screen-shot, photograph or save an image.

Armed with strong evidence the district failed to protect Fletcher from ongoing harassment, plus lack of facts from a most cursory investigation of student claims, Hopper Donahue delivered a long speech to the school board as it considered the superintendent’s request to refile charges in closed session.

On that night in August, the board listened and reversed course – agreeing to give Fletcher a large monetary settlement and positive recommendation. She agreed to resign and drop the EEOC complaint.

“This case just shows how emboldened school districts have become to go after teachers whenever they want to,” Hopper Donahue said. “Bethany’s children may be too young to understand, but she set a lesson for them to see what happens when you stand up for yourself.”

Fletcher says she didn’t do it alone: “If not for MEA, I would not be here today. They collectively gave me my life back.”

She believes the students who falsely accused her didn’t mean it to go that far and the school board assumed the district had real evidence. She advises educators to join the union and advocate for each other. “You don’t realize how powerful it is to have union support in a crisis until it happens to you.”

Now a few months out from the turmoil, Fletcher still doesn’t know if she will return to teaching. “When people ask what I’m going to do with my life, I say ‘I don’t know; it’s a surprise.’ But thankfully I have options today where I didn’t see that I had options before.”