Veteran of combat and classroom earns rare recognition

By Brenda Ortega

MEA Voice Editor

From the get-go, Jim McCloughan was competitive “with a capital C,” he says.

Small and athletic, he excelled at every sport he tried. At Bangor High School in the early 1960s McCloughan earned 11 varsity letters and all-conference honors in football, basketball, baseball and track, despite standing just 5-foot-2 and 130 pounds at graduation.

His competitive spirit also helped him overcome undiagnosed dyslexia that made reading difficult. He combined workarounds with a willingness to put in extra hours completing assignments and learning material to graduate near the top of his high school class.

He would go on to compete in football and baseball at Olivet College where he added wrestling to his repertoire. Despite inexperience in the new sport, McCloughan achieved back-to-back conference wrestling championships in his junior and senior years.

When his wrestling coach suggested McCloughan would make a good teacher and coach, his future took shape. He completed student teaching, earned a bachelor’s degree in sociology, and signed a contract to work in South Haven Public Schools in May of 1968.

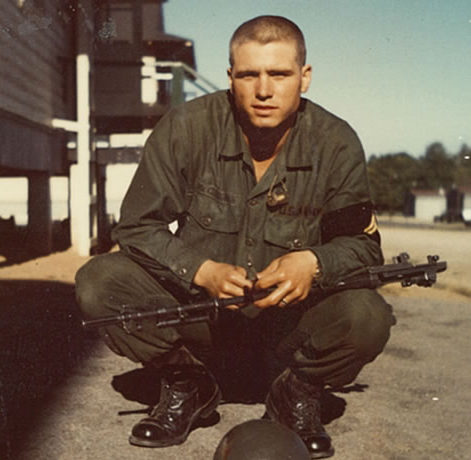

That summer he prepared for the job and coached junior varsity football until fate intervened. McCloughan received a draft notice from the Selective Service System ordering him to report for military duty at the height of the Vietnam War.

He left for basic training in August, underwent advanced training two months later, and deployed to Vietnam as a U.S. Army combat medic the following March.

McCloughan credits lessons learned from coaches, teachers and family members, along with skills and toughness developed through sports — especially football and wrestling — for his survival. In particular, he believes wrestling saved his life.

“That’s where I learned mental discipline that gave me the ability to focus on this wounded soldier in the kill zone, while my men are firing at the enemy, the enemy’s firing at my men, and me and this guy are in the middle of it,” he said in an interview.

In 1970, he returned to teaching and coaching in South Haven with a newfound mission: “I wanted to prepare my students and athletes for their own ‘Vietnam,’ because everyone will face challenges in life — whether it’s your parents divorcing, your house burning down, losing a loved one, whatever it may be,’” he said.

“I wanted to build them up and give them tools to make good decisions.”

Nearly 50 years later, McCloughan received the Congressional Medal of Honor — the military’s highest decoration for gallantry and bravery in combat at the risk of life, above and beyond the call of duty, for his life-saving actions during a fierce two-day battle in May of 1969.

“It’s what my father taught me at a young age. He told me, ‘Jim, you never do anything halfway. You do it to the best of your ability, and you do it until the job is finished.’”

IN SCHOOL

McCloughan got his first taste of teaching as a third grader attending Wood School, a one-room K-8 schoolhouse in Bangor Township still in operation today. He loved to be one of the big kids helping younger ones, and the repetition solidified his own learning, he said.

Born in South Haven, he moved at age one with his family to an old farmhouse not far from the school, with no electricity or running water, which had been owned by paternal grandparents.

His father was his hero, a jack-of-all-trades who turned the shell of a house into a home over years, he said. Both parents held jobs — dad at Everett Piano Company and mom at Bohn Aluminum — and he and two brothers built a solid work ethic helping around the house.

He has memories of his parents’ dinner plates being less full to ensure the children had enough to eat, but adds, “We weren’t poor; we just didn’t have money. That’s all there is to it. We were really rich with love.”

In addition to athletic abilities, McCloughan showed a talent for singing from a young age. He made his first public appearance at age five, performing “Amazing Grace” at church, and still remembers the name of his elementary traveling music teacher, Mrs. Dykstra.

He transferred to “town school” in Bangor Township in seventh grade, into bigger classes grouped by age. “I was a boy soprano, and I was 4-foot-7, which set me up for a little bit of trouble until they heard me sing.”

He transferred to “town school” in Bangor Township in seventh grade, into bigger classes grouped by age. “I was a boy soprano, and I was 4-foot-7, which set me up for a little bit of trouble until they heard me sing.”

By high school, in addition to making his mark in four sports, McCloughan held leading roles each year in school musical productions.

Returning to South Haven to teach and coach in the schools where his father grew up and graduated was a dream come true, he said. McCloughan taught psychology and sociology at South Haven High School, retiring after 40 years of service in 2008.

Former students quoted in news accounts after his retirement remembered McCloughan as genuine, caring, inspirational — “a true gem” known for his humor, engaging style, and the life relevance he brought to lessons.

He also coached high school football and baseball for 38 years, coached high school wrestling for 22 years, served as a wrestling official for 25 years (selected to officiate 18 wrestling state finals), and coached American Legion baseball in summers.

He says one of his greatest blessings, outside of coming home alive from Vietnam, was coaching his own two sons who were excellent athletes and have become excellent men.

Among other honors, McCloughan has been inducted into the Michigan High School Baseball Coaches Hall of Fame, the Michigan High School Football Coaches Hall of Fame, the Michigan High School Coaches Hall of Fame, and the National Wrestling Hall of Fame.

A former player from one of his football teams, C.A. Cunningham Sr., described McCloughan as “selfless” and “charismatic” in a television news interview recalling an undefeated season in 1989. “He taught you to not quit and never surrender, never retreat,” Cunningham said.

Cunningham became a science teacher and assistant coach in South Haven, working alongside McCloughan. Now an MEA-Retired member who owns a Kalamazoo-area lawncare and landscaping business, Cunningham described his mentor as “a builder of men.”

However, it wasn’t until McCloughan finally slowed down in retirement that he realized the busy schedule of teaching and coaching for decades had served another purpose — to keep his memories of Vietnam at bay.

Suffering from symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), including nightmares, he was steered into help by a benefits advisor at the Veterans Administration (VA) who noticed a change in him, McCloughan said.

Eventually he sought help from a VA counselor, a paraplegic Marine combat veteran who “walked me through my war experience.”

Despite having earned a master’s degree in guidance and counseling at Western Michigan University back in 1972, McCloughan discovered, “You can’t counsel yourself.”

IN BATTLE

His grandfather fought in World War I, his father in World War II, his uncle in the Korean War. Drafted at age 22, McCloughan figured his time to serve had arrived, yet it still came as a big shock when he finally got the frontline assignment.

At one time he thought he might get an Army teaching job after training. But college classes he’d taken to complete a physical education minor — in physiology, anatomy and first aid — made him a fit as a combat medic.

He admits to taking a walk to process the news, sitting at a playground, and crying. Then he gave himself a pep talk. “I said, ‘Jim, you better change your attitude or you will die in Vietnam and you will not be a teacher. You better get ready to be the best soldier that you can be.’”

He was assigned to Company C, 3rd Battalion, 21st Infantry, 196th Light Infantry Brigade, Americal Division. Stepping off the helicopter in Vietnam, he was met by two sergeants.

Sgt. Doug Hatten, who was missing a tooth, wore a crooked helmet, and spoke in a slow drawl, saved McCloughan’s life in combat on that first day, he said. Two men from the unit were wounded, two were killed, and McCloughan killed an enemy combatant for the first time.

“I was stunned, and that guy with the missing tooth and crooked helmet slapped me. He said, ‘Doc, that’s the way it’s going to be. Do you understand? It’s you or him.’”

All medics were called Doc, and that’s the name McCloughan became known by. During his time in the unit, he was involved in several major battles, but on May 13 a bloody clash began to control Nui Yon Hill in Quang Tin province which would change and define his life.

All medics were called Doc, and that’s the name McCloughan became known by. During his time in the unit, he was involved in several major battles, but on May 13 a bloody clash began to control Nui Yon Hill in Quang Tin province which would change and define his life.

McCloughan is credited with saving 11 lives, including 10 fellow soldiers and a Vietnamese interpreter, by venturing into the line of fire multiple times over 48 hours of fighting that concluded on May 15.

He was injured three times by shrapnel and gunfire during the struggle but refused orders to evacuate. “I said, ‘You’re going to need me. I’d rather be dead in a rice paddy than alive in a hospital knowing one of my men died because Jim McCloughan wasn’t there to do his part on the team.”

A second medic assigned to the company, Private First Class Daniel Shea, performed similar life-saving actions in the battle and was killed in action, leaving McCloughan as the only medic on the ground. Shea was awarded a posthumous Medal of Honor.

“I held 18-, 19- and 20-year-olds in my arms, heard their last words,” McCloughan said. “Some of them were talking to God, and some didn’t believe in God until it was right there, time to cross over. Some were calling me Mom. Then I saw the last breath of life come out of their body.

“I know that the price of freedom has been paid for in full.”

Heavily outnumbered, the unit saw 14 soldiers killed and 43 wounded of 89 total. McCloughan didn’t expect to survive. At one point, crouched in a trench, applying pressure bandages to a man with a serious abdominal wound, he wondered how to carry the soldier to safety.

He couldn’t sling him over his shoulder. He decided he would hold the wounded man against his chest, get low to the ground, and race through the crossfire.

Suddenly a thought occurred: “It had been since I was a little boy that I told my father that I loved him.”

He made a pact with God. “I said, ‘Lord, if you get me out of this hell on earth so I can look my father in the face one more time and tell him that I love him, I’ll be the best coach, I’ll be the best teacher, and I’ll be the best dad that I can be.’”

McCloughan did his best to keep his word, he says.

IN MEMORY

One of the ways McCloughan tried to heal old traumas after his retirement from teaching was to seek out his old Company C comrades. In some cases, it took internet sleuthing. Finding Sgt. Hatten required more than 80 phone calls because he wasn’t sure how to spell the last name.

He was able to reconnect with 23 people from his unit, including Hatten, who had returned to his childhood home in a rural town in Eastern Washington. McCloughan later spoke at his funeral.

Some of the most meaningful moments came from contacting family members of those who didn’t make it home, he said.

One of the men killed on McCloughan’s first day in country had been proudly showing a photo he’d just received of his newborn son hours before he died. “He’d only been there a couple weeks.”

One of the men killed on McCloughan’s first day in country had been proudly showing a photo he’d just received of his newborn son hours before he died. “He’d only been there a couple weeks.”

McCloughan tracked down the son from the photo, grown and married, and called him in Arizona. “He never got to know his dad, but I got to tell that man, ‘The last thing your father did was to brag about you and show everybody in his unit your picture.’”

And in 2019, McCloughan heard from a descendant of the first man he saved in the Nui Yon Hill battle. He had run 100 yards under fire to carry the injured soldier to safety.

“This letter said, ‘You don’t know me, and I don’t know you, but you saved my grandpa in 1969. My mom was born when Grandpa came home in 1970. I was born in 1991. Last week, my wife and I had a baby boy, and this Sunday I get to celebrate Father’s Day because of you.’”

McCloughan received two Bronze Stars and three Purple Hearts in the battle’s aftermath, but his road to receiving a Congressional Medal of Honor took 48 years and bipartisan action from former U.S. Reps. Fred Upton and Carl Levin, Sen. Debbie Stabenow, Congress, and two U.S. presidents.

In 2009 a lieutenant from Company C revived efforts to award a Distinguished Service Cross to McCloughan, who still gets emotional listening to a saved voicemail from 2016 in which Stabenow reports that Defense Secretary Ash Carter upgraded it to a Medal of Honor.

Stabenow helped pass a bill waiving a five-year limit for granting the Medal. President Barack Obama signed the bill in December 2016, and President Donald Trump presented the Medal of Honor to McCloughan in July 2017.

Only 3,465 Medals of Honor have been awarded in all of U.S. military history, and just 61 living Medal awardees remain as of this writing. McCloughan insists the Medal is not his but belongs to the unit’s 89 soldiers who fought bravely, especially those who gave their lives.

The Medal’s significance means McCloughan is in demand at age 79. He spends many weeks every year traveling the country speaking to veterans’ groups, non-profit organizations, students and others. He raises money and serves on boards of non-profits helping veterans and their families, along with related causes.

His busy time of year is the fall when he is often away from home for more than half the days between Sept. 1–Nov. 30, according to his wife Chérie, a retired English teacher from South Haven, who is his scheduler and travel arranger.

He writes his own speeches, tailored to groups he addresses. He makes a point with veterans to discuss mental health and to reframe the Vietnam War through the lenses of those who lived it.

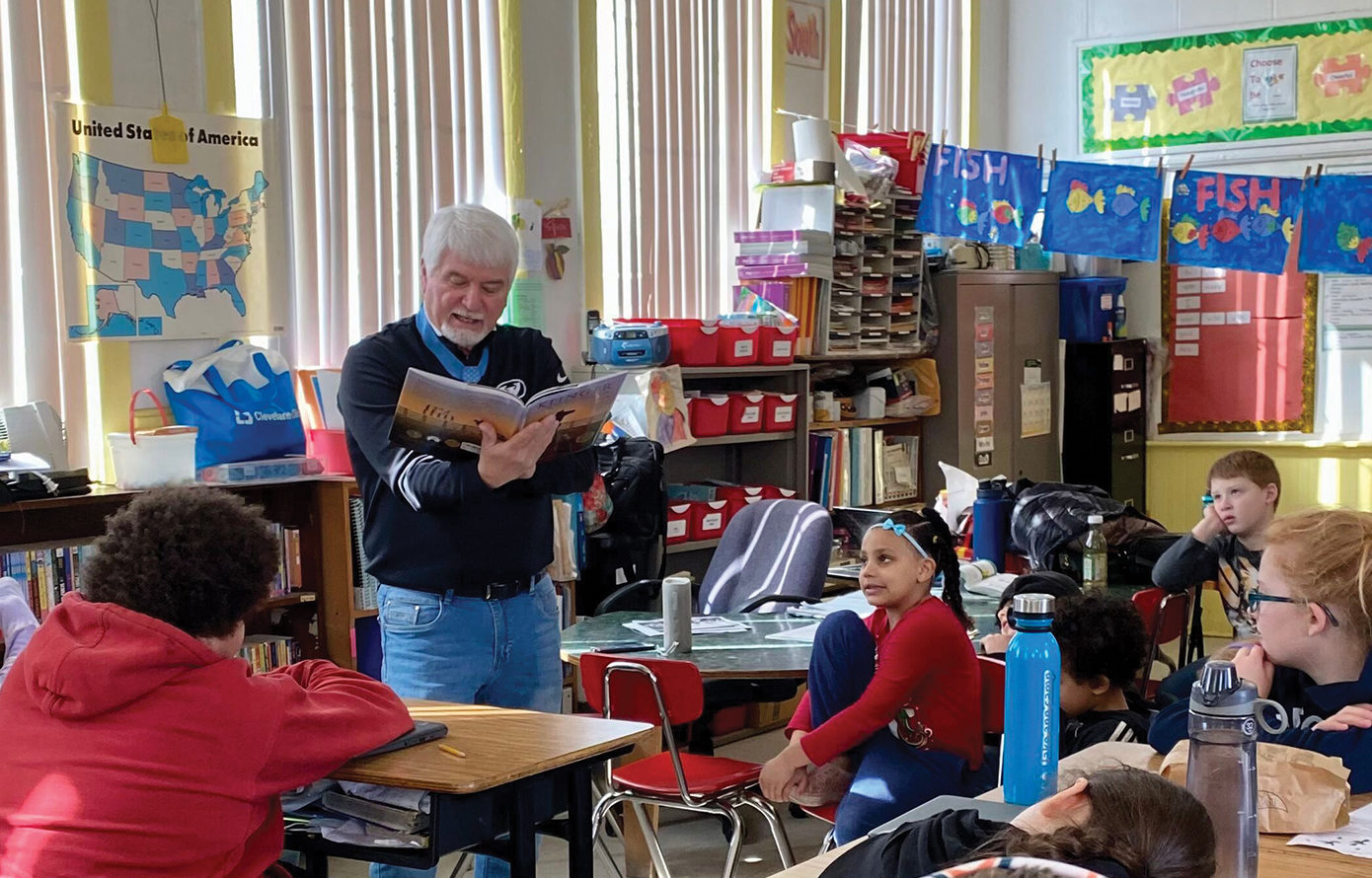

With students, he focuses on character development, continuing the mission that began with his battlefield vow long ago. McCloughan is chair of the Character Development Program, a free K‑12 curriculum offered by the Congressional Medal of Honor Society.

He ends his speeches by giving audiences an assignment he’s handed to thousands of students, athletes and coaches since he returned from war: Tell a special person you love them.

“There must be someone you haven’t been able to say those three words to,” he says. “Not on purpose; life got busy. Look them in the eye and tell them, ‘I love you.’ If you can’t look them in the eye, use your phone. And there’s a Part B to this homework: Tell them why.”

Read more about McCloughan, the Medal and his ongoing work:

Free! K‑12 Medal of Honor Character Development Program

Jim McCloughan’s advice to educators

MEA helps veteran win court battle