Small district, big battle: Educators and community in southwest Michigan town push back against extreme school board

By Brenda Ortega

MEA Voice Editor

Things weren’t going according to plan at a recent meeting of the board of Brandywine Community Schools in Niles, where community opposition is growing as a new board majority has begun to enact an extreme political agenda targeting library books and teaching materials.

Missing two of its seven members, the school board was unable to agree on an agenda to get started.

With about 75 people watching from the audience — including educators, parents, and students wearing matching red shirts and waiting to speak — the newly elected board president, who leads the newly elected ultra-conservative majority, abruptly ended the meeting 11 minutes after calling it to order.

“Meeting is adjourned, thank you,” board president Thomas Payne declared after a few minutes of questions and disarray, reversing course after first saying the agenda for the Feb. 27 meeting was approved by a 3-2 vote.

Superintendent Travis Walker had just interjected to clarify the board’s bylaws require a majority vote of elected officials to pass a motion — not merely a majority of the quorum in attendance — so four votes were needed.

“Do we still have to have public comment, though?” asked third-year board member Jessica Crouch, now in the minority of many 4-3 votes since the four new board members were seated in January.

“No,” snapped Payne, gathering his papers and materials into a folder. “Agenda’s not approved.”

From the audience, a man shouted a rule from the manual of parliamentary procedure known as Robert’s Rules of Order: “Adjourning requires a motion!”

“The agenda doesn’t exist —” Payne began, speaking into the microphone, but was stopped by the man’s authoritative tone even above shouts from others in the audience for Payne to resign.

“It doesn’t matter — you called the meeting; adjourning the meeting requires a motion.”

“I move we adjourn the meeting,” said board member Elaine McKee, one of the four elected last November with financial backing in part from “We the Parents,” a group in the region that espouses the need for “faith, family and freedom” to replace supposed “indoctrination” of children in schools.

“Second; meeting adjourned, thank you,” Payne declared again — with a pound of the gavel and no vote — standing to scoop up his materials and walk briskly out of the high school gym, where meetings have been held to accommodate the crowd.

That is when something remarkable happened.

As dozens in attendance gathered belongings and chatted about the turn of events, Brandywine’s white-haired former superintendent — John Jarpe — stood from a seat in the audience near the front and turned to face the crowd, waving both hands to say, “Excuse me,” above the murmur.

“It seems to me you all came here tonight to say something, and maybe you ought to be able to say it,” he said, making his way to the center aisle. “I’ll go first.”

A 43-year educator, Jarpe is well known and respected in the area, having served as a teacher and/or principal in Brandywine and St. Joseph, both in southwest Michigan’s Berrien County. He was superintendent of Brandywine for 10 years before his retirement in 2017.

A month earlier, he’d been featured in local news coverage of a contentious Jan. 23 meeting in which he told the new board he was “heartsick” at conflict surrounding the district and asked novice members to slow down and learn before making changes — or risk losing employees to other schools.

Now he was acting as an impromptu organizer, offering people a chance to have concerns heard and connect with each other even though the meeting was over. Four board members — including two of the newly elected four — stayed to listen.

Had the meeting continued, Jarpe said, his message to the board would have been to say removing books from the library or dictating what can be taught in sex education or any other course — none of that is addressing real problems facing schools or parents or communities.

“Tonight I was going to urge the board to take on chronic absenteeism,” he told the crowd, nearly all of whom remained for about half an hour. “That is a big problem just about everywhere you look and absolutely critical to a student being able to learn. I was going to say take that on and fund it, figure that out, and you’ll have people coming to Brandywine asking ‘What’d you do? How’d you do it?’”

From the outset, the new board majority has focused on forming several committees to make recommendations on library books to remove, classroom curricula to change, and sex education topics to teach or not teach, among other issues.

In addition to We the Parents, which opposes dialogue about race and LGBTQ+ people in schools, the four board members are backed by 1776 Project PAC, a political action committee trying to elect school board members nationwide to push “patriotic” history and ban classroom discussions of racism.

When Jarpe finished, a parent stood to speak who said she regrets voting for the four new board members and agreed the panel needs to address problems that will help students be successful.

“It is frustrating to see the agenda focusing on books currently in the schools and not on making sure students can get to school,” said Jen Unger, who has three children in the district. “The shortage of school bus drivers and the posted positions that are still not filled were not discussed.”

Another parent brought up a frequent complaint: that board action precedes scheduled public comment. Ryan Adams, father to a Brandywine graduate and a current student, said the community must ensure the board’s new committees — formed without public input — follow the state’s Open Meetings Act.

“That means handpicked committees don’t get to hang out at the gym and decide which parts and pieces of sexual education to teach,” he said in a fiery speech. “It means handpicked committees don’t get to sit at Sunday social and decide the future of our schools’ curriculum. Not without the public viewing the gathering…

“Be transparent. It’s going to be in the community’s interest that the order in which the committee meeting agendas are organized puts our participation before decisions, before action, before recommendations.”

Lakeisha Byrd, the only Black parent in attendance who spoke, said she was “shook to my core” when she researched values and beliefs of We the Parents before voting last fall. What she found were “divisive” statements about gender, patriotism, and “woke” school boards, she said.

A second-generation Brandywine graduate whose mother was in the first graduating class of 1963, Byrd said she and her husband moved back to the area specifically so their kids could attend the schools.

“If We the Parents principles are based on respecting our rights as parents… I ask that you indeed respect the rights of all parents and teach all of our history and you include all of our children,” she said, reading from prepared remarks, adding the board should not favor “a single constituency” but should unify and build on district strengths.

The stability of the district has been imperiled by the new board’s actions, said Brandywine District Education Association (BDEA) President Debbie Carew, an English language arts and humanities teacher who grew up in the district and has taught there for 26 years. Former superintendent Jarpe was her fourth-grade teacher.

Carew shared with the crowd preliminary data from a staff survey she was conducting.

From the staff of 80 teachers, of the first 40 who took the survey 100% agreed the school year started out with positive momentum and high spirits, Carew said. A talented new superintendent hired just last spring had already begun building a powerful culture of collaboration, she explained.

“In a really stark contrast to that, now 62.5% of those same people have considered leaving the district or retiring earlier than planned due to this recent turmoil,” Carew said. “That’s a drastic change in our morale since January, and that’s about a third of our staff that have considered leaving.”

Nearly all respondents — 85% — said the disruption and tension were negatively affecting their health. “We’re headed for much bigger problems if we have our amazing teachers, administrators and staff decide that calmer waters would be best for their personal well-being or career,” she warned.

WHAT’S HAPPENING at Brandywine is not unique. While the majority of extremist candidates lost their bids for school board seats across the state, wins in scattered races for candidates backed by far-right groups such as Moms for Liberty, FEC United, or Ottawa Impact tipped control of some boards and altered the makeup of others without a full takeover.

For example, in Grosse Pointe, a new conservative board majority torpedoed a planned high school-based health clinic, hired its own legal counsel independent of the district’s attorneys, and — as in Brandywine — formed committees to wade into hot-button issues right out of the gate in January.

In Allendale, a new board majority quickly fired and replaced the district’s legal counsel. They also heard testimony from a well-known alum, Ruth Crowe, a successful artist who said the new regime dis-invited her from helping at an art workshop for high school students because she is gay. Crowe demanded to be removed from the district’s Hall of Fame.

But in Brandywine, a small district of three schools, the four new board members all were elected at once and touted nationally by the 1776 Project as one of its biggest successes. The PAC claims to have won 100 races across the U.S. and flipped 10 school boards with its “parental rights” agenda.

The tight coordination of messaging and objectives among right-wing groups in the last election — from school board contests up to gubernatorial races — was not a coincidence, according to Josh Cowen, a researcher and professor of education policy at Michigan State University.

The same groups that for decades have pushed for states across the country to adopt destructive Betsy DeVos-style voucher schemes — proven to have harmful effects on educational outcomes — are now funding the “culture war” battles to ban books and demonize LGBTQ+ people, Cowen has written.

“The school privatization movement and with it the Right’s attacks on public education are some of the most extreme forces operating today in American politics,” Cowen wrote in a January op-ed published by the Network for Public Education.

“Extreme, and ultimately very dangerous,” Cowen concluded. “Defending public schools is becoming increasingly a movement to defend human rights.”

Debbie Carew, the local union leader, said the BDEA did not make voter recommendations in November’s election. She believes the four were elected because they had lots of outside money paying for yard signs and many people in the community didn’t realize what they stood for.

“They weren’t attending our school board meetings and making a lot of noise about masks or books over the past few years like you saw happening in other places, so people have been surprised,” she said. “And now that they know, they’re getting active in pushing back.”

Carew and her vice president, Abby Janke, have been keeping members informed and building solidarity as membership has grown since the election. Since taking over the VP role last fall, Janke’s job has been to attend board meetings, take notes, and report back to the local.

“This has been a good role for me because it helps me feel empowered to make sure we’re keeping abreast of what’s happening and not getting blindsided by things,” Janke said. “We’re a good team.”

Lately educators have been among the dozens regularly turning out for school board meetings with many speaking and others wearing red in the audience in a show of numbers.

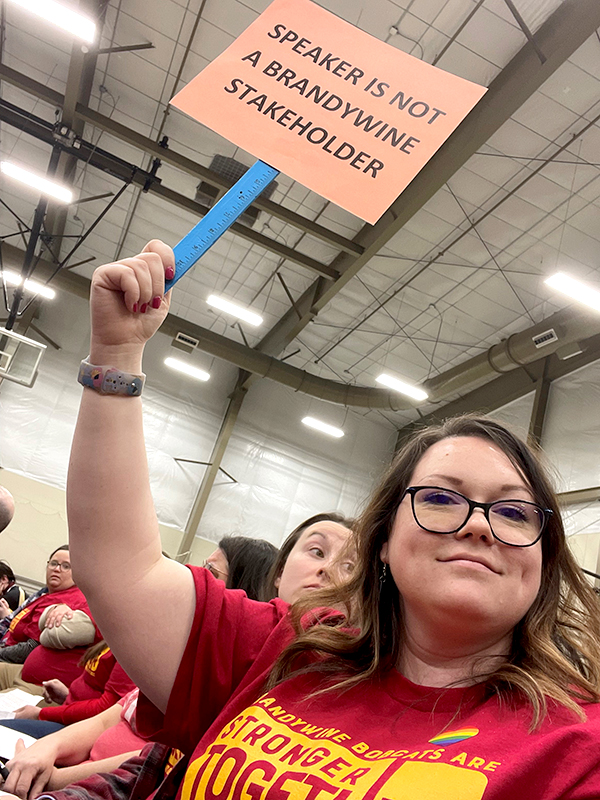

At a Feb. 13 board meeting, several people appeared in support of the board, but nearly all of them came from St. Joseph or Stevensville 30 minutes away. Brandywine staff fashioned signs to hold up during district outsiders’ testimony which read, “SPEAKER IS NOT A BRANDYWINE STAKEHOLDER.”

The biggest concerns expressed by educators, students, parents, and community members at several meetings in a row surround the board’s combative stance toward school employees, along with the alarming potential for book bans, restrictions on teaching, and marginalization of LGBTQ+ youth.

Some students created a group called “We the Students” and distributed flyers at board meetings that explained, “We want to see the LGBTQIA+ community supported, we want to not see books banned in the library, and most importantly we want to protect our rights as 21st century learners.”

Several students have spoken at board meetings, including senior Kiersten Colby, who helped organize the group. Colby reminded the board that parents have the right to opt out their own children from books or learning they find objectionable, so a committee is not needed to eliminate materials for all.

“Where’s the transportation committee that will find more drivers to get behind the wheels of our buses to ensure efficient, timely, and safe transportation for our students to and from school or events?” Kiersten asked. “Where’s the teacher retention committee to ensure the school attracts and keeps quality teachers in front of students during a time of a teacher shortage?”

District alumni have also played an important role in opposing the board’s agenda. Twin sisters Ambrosia Neldon and Jasmine LaBine — who graduated in 2009 — started a Facebook group, Brandywine Alumni, Parents and Educators for Educational Freedom, which quickly grew to nearly 700 members.

Being the first generation in their family to graduate from college, both value the education they received at Brandywine.

LaBine is a professor of communication at Western Michigan University and a visiting assistant professor at Albion College. Neldon is the former editor and publisher of the hometown newspaper, now working as communications manager for Cass County and living four houses from the high school.

“My life was shaped by some of the teachers that I had,” Neldon said in an interview. “I know for certain I wouldn’t have taken the career path that I have without my teachers at Brandywine. It breaks my heart to see what they and the students at the school are going through.”

Recently named a Distinguished Alumni by the district’s alumni committee, Neldon said a significant number of the Facebook group’s members are people who voted for the four board members and now feel they were “bamboozled.”

“They may have had some frustrations with things like masks or the way COVID was handled, but we have people from all over the political spectrum who agree the school board is no place for politics. There’s a reason why it’s non-partisan, and there is no reason to make a battleground of our schools.”

A small city of just under 12,000 residents, Niles and the surrounding area is home to two school districts and historically, the community is protective of its schools, Neldon said.

In the case of Brandywine, with a K-12 population of about 1,200 students, there is no corresponding town; the school district is what brings people together and creates the community, she said. “We’ve seen something like this happen before, and people tend to come out in droves and say, ‘Not our school. This isn’t happening.’”

The community’s push-back against the board so far seems to have resonated. The day after the February board meeting that was unexpectedly cut short, the board’s president appeared on a talk show podcast, hosted on the far-right Rumble platform, to “set the record straight.”

The show’s host, Casey Hendrickson, described opponents of the board as “a teachers’ union‑organized insurgency” while Thomas Payne — the board president — argued there is no plan to ban books or teaching materials as people have opposed. Then he appeared to contradict himself.

The board is merely reviewing books “to see if it is of educational value to the kids, and if it’s not, the primary reason for the kids to be there is to be educated. And to have this kind of material doesn’t make sense. Personally, I don’t think so. I think it’s gross. But that’s up to the board to decide.”

On that point, BDEA President Debbie Carew reached out to another distinguished graduate of the district to make a case for intellectual freedom: Diane Seuss, who graduated from Brandywine High School in 1974, became a university instructor, writer-in-residence, and highly regarded poet.

Seuss, whose mother was a high school English teacher in the district and father was a guidance counselor before his untimely death at age 36, was awarded the Pulitzer Prize for Poetry and the National Book Critics Circle Award for Poetry last year for her fifth collection, titled frank: sonnets.

In response to Carew’s call for help, Seuss penned a lengthy open letter to the Brandywine school board, describing the school family that supported her through her father’s illness and developed her as a person.

“I don’t believe any of my accomplishments would have happened without my time at Brandywine,” she wrote. “Books were freely available in the library. Challenging books. Even controversial books. My mom taught some of them in her classrooms, and kept those students who might have otherwise checked out engaged in discussions of literature to which they could relate, or even about which they could argue.”

Seuss urged the board not to turn Brandywine into a school system without freedom of thought and expression.

“You risk alienating hard-working professionals who are, in fact, experts in their fields. You risk shutting down the imaginations and intellectual adventurousness of the students. A surefire way to turn off students to their own educations is to control them into submission.”

Carew found the letter moving, and read it aloud to the board. But equally profound, she added, was a message she received from a former middle school student of hers — now a senior — who was her checkout clerk at a recent trip to the grocery store.

While ringing up groceries, he confirmed the senior class was moving to have teachers hand out diplomas this spring, instead of the school board as tradition would have it, and he would be asking to receive his diploma from her. Then he thanked her for caring about him in class.

“I went out to my car and had a big, hard cry,” Carew said.

The BDEA vice president, social studies teacher Abby Janke, agreed that seeing students, parents and a broad swath of the community coming together in defense of the teaching and learning happening at Brandywine schools has been gratifying in a way that’s hard to describe.

“It feels so personal when people are attacking the thing I love, the job I wanted to do since I was 14, but seeing the love for Brandywine flowing at these meetings — it just feels energizing,” Janke said.

Related:

After threats and abuse, Rochester member rebuts school board trustee’s claims