Flint teachers hold the line to ‘breathe easier’ after long battle

By Brenda Ortega

MEA Voice Editor

In January when seven school board members of Flint Community Schools voted down a settlement agreement between the district and its teachers, their move sparked a crisis which spun into a dramatic three-month showdown culminating in a huge win for United Teachers of Flint.

But the historic victory was actually 10 years in the making.

The conflict that erupted with the board’s bizarre Jan. 12 vote began brewing back in 2014 when Flint teachers accepted double-digit concessions to help pull the district out of deficit spending. For a decade since, frustrations mounted over continuous salary step freezes.

“Our people had enough, and they were done,” said UTF President Karen Christian, a sixth-grade teacher determined to free educators trapped on steps since she first won election in the concessionary contract’s wake. “I vowed long ago I wouldn’t leave until it was finished.”

The 33-year veteran achieved her goal this spring after weathering enormous challenges – from large-scale disasters such as the Flint water crisis and the global pandemic to personal battles against breast cancer and a 2020 bout with COVID that landed her in a hospital intensive care unit.

“It’s a cliché, but I know every teacher in this district on a first-name basis; we’ve been together my entire career, and we really, truly are a family,” she said. “I just knew I couldn’t stop until every single one of them was fully restored – back to where they rightfully belonged.”

Among other improvements, the agreement approved by the board following weeks of tumult makes whole all teachers still moving through the pay scale, advancing them to the step on the salary schedule reflecting their years of service – retroactive to the beginning of last school year.

For many the raise was significant, and for others life-changing. The largest annual pay increase one member received after moving up multiple steps was $28,000. Those already at the top – including Christian – made one retroactive step in May and will take a final one in August.

Negotiated as a grievance settlement, the deal also allows the district to lure experienced applicants by offering higher pay to start. At a joint press conference, both sides celebrated its potential to boost the district by retaining Flint’s teachers and attracting new and veteran talent.

Third-year Superintendent Kevelin Jones said, “The teachers’ union and the administration have a level of trust to know that when we sit down together we’re all trying to do what’s best for our scholars. We’re going to keep building on that trust to move this district forward.”

Christian credited Jones that employees felt safe speaking out. “It was important that teachers felt listened to as they shared stories of trauma they’ve been through and their students have been through. It made a difference that allowed us to get back to the table and reach this agreement.”

Christian casts a long shadow in Flint. She attended district schools, where both of her parents were teachers and her mother was a union activist. She remembers walking picket lines in the 1980s alongside her mom and dad. Her three grown children are Flint graduates.

It’s been painful to watch caring educators leave the district, she said: “You feel bad because they really didn’t want to go, but they had to fend for their families. Now we have this deal for all the teachers who stayed. But mostly it’s for Flint kids. They deserve the best.”

The crisis campaign waged by UTF centered Flint’s young people. The school district had seen an exodus of educators as surrounding districts began offering steps to experienced new hires amid the teacher shortage. Openings in Flint went largely unfilled, and less qualified substitutes stepped in.

“Flint students are in crisis,” Christian told board members at a packed meeting on Valentine’s Day. “The crisis that they’re in is trying to learn in overcrowded classrooms. The crisis they’re in is not having certified teachers in every classroom.”

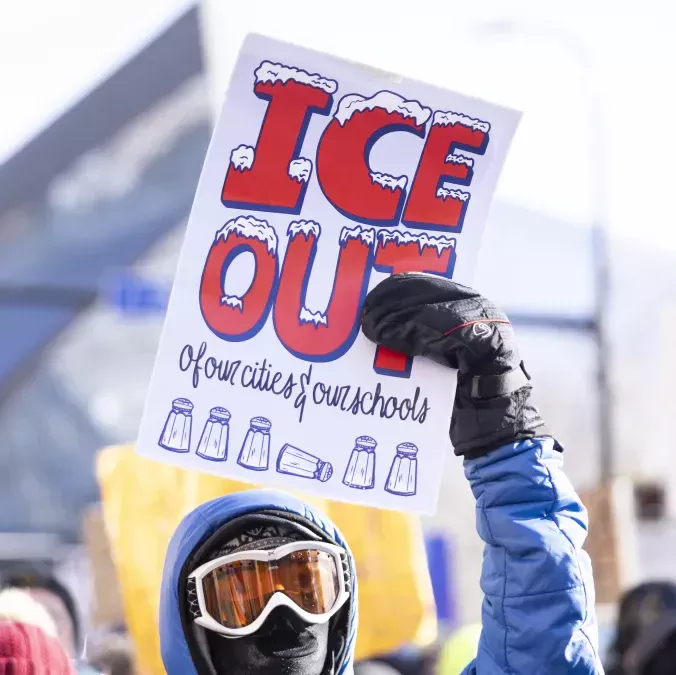

Union bonds were strengthened as crisis actions escalated from issuing press releases to filing an Unfair Labor Practice (ULP) charge, picketing and testifying at school board meetings, eliciting union support from across the state, posting multiple billboards across town, pulling off a mass sickout, and unanimously authorizing a strike.

The unit’s membership grew from 60 to 85% in those weeks, a point Christian emphasized during public testimony. “Do you see all of us here? We’re all united. We want to be treated like professionals… and we want to be able to retire with dignity.”

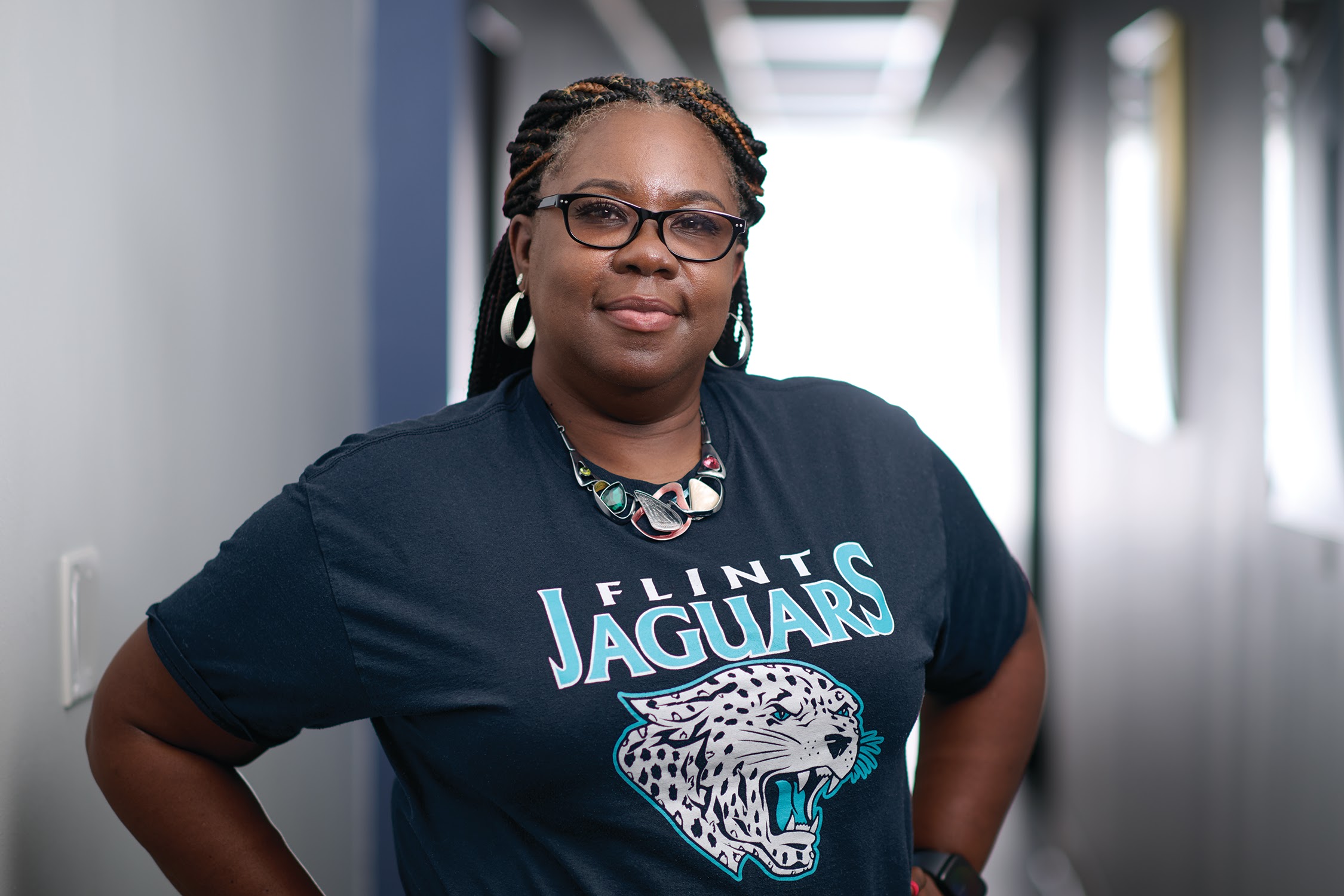

UTF Vice President Trishanda Williams, a Flint schools alumna and 22-year veteran who teaches marketing and Intro to Engineering Design at the high school, summed up the message in an interview: “Teachers are the heartbeat of our schools. Without them you have no district.”

Like others, Williams has foregone higher pay elsewhere out of deep commitment to Flint’s community and children. The stories educators told were heartbreaking, she said.

“We’ve had teachers working two jobs and still spending paychecks to provide what’s needed – whether that’s school supplies, food, clothing, personal items. People lined up to tell their stories and essentially what they said was we make sacrifices and the district has benefited. We do it because we want the children to have all that we had growing up.”

MEA President Chandra Madafferi noted the disparity in resources between high-poverty districts and wealthier ones when she testified at a late February board meeting. She pinned Flint’s plight on failed state policies from a dozen years ago which starved schools of resources.

The depth of the crisis is not your fault, Madafferi told board members, but “if you choose to hold the line, you’re still losing great educators. And the students lose… I’m asking you again to please honor the agreement that was made in good faith by your educators and your administrators.”

The settlement deal grew out of pay and workload grievances filed by UTF last year, said MEA UniServ Director Bruce Jordan, a former Flint teacher who was laid off amid district budget cuts in 2013 before taking over the staff job serving the unit.

“We leveraged a bunch of things like elementary planning periods which they don’t provide to the contractual extent they’re supposed to,” Jordan said. “They were also hiring in people above others who were frozen. Those grievances were already scheduled for arbitration, and they were slam dunks.

“This agreement settled all of those grievances,” he explained, noting that Christian’s mother trained him up in the union – as she did others – when both worked at Northern High School. “And now Karen and I have been singularly focused on this issue for 10 years, and we finally are able to breathe.”

An earlier settlement hammered out last fall first raised hopes, then crushed them. That deal – very similar to the one approved recently – was mediated by the Michigan Employment Relations Commission (MERC) in talks between the union and district administration, including board members.

The union’s membership approved the original tentative agreement in November, but weeks later the school board took its highly unusual January vote to back out of those agreed-upon terms.

With that move, a fundamental shift occurred within United Teachers of Flint. Years of pent-up frustration became palpable indignation as educators and their supporters filled the auditorium at board meetings for weeks, chanting “Shame” and “We are done.”

It wasn’t easy for people to speak up publicly, Christian said. “A lot of times we want to keep our trauma buried to ourselves. But for those teachers that bared their personal stories, they felt this was the moment.”

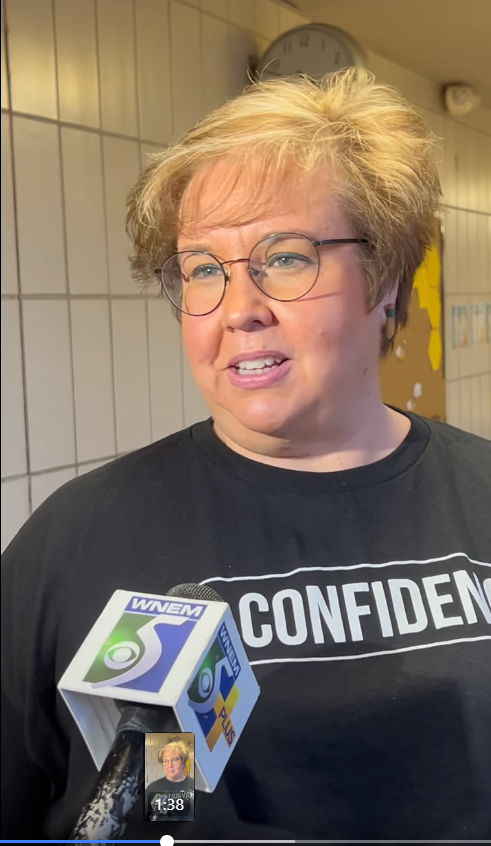

MEA member Krissy Gatz, an elementary teacher in the district for 31 years, came to tears telling the board she didn’t know if she could stay and worried who would be left. The 19% pay cut teachers accepted in 2014 plus step freezes since have “cost me a great deal,” she said.

Asked to elaborate after the meeting by a television news reporter, Gatz hesitated before acknowledging on camera, “Remembering this is painful. I lost my house.”

After losing one-fifth of her income, she couldn’t keep up with bills, she said. “There were times when I couldn’t afford food. Being proud… I would give my dogs to my family and lie, ‘I have a teacher meeting this weekend; could you take my dogs?’ So then my dogs would have food.”

Gatz has been living with her brother as she rebuilds, she said. She stayed in the district, “because I love Flint; I am Flint. I’m a Flint kid, and I had Flint teachers who loved me. It’s my turn to love Flint kids, but I need to love me and my family as well.”

Teachers who left the district also wrote letters or returned to talk about why—such as Nadia Rodriguez, who worked in the Montessori program at Durant-Tuuri-Mott Elementary.

“You all know my story,” she told the board. “I’ve always been proud to have been a product of the Flint Community Schools. It was my dream to be a part of the staff, build relationships with students in my community, and to be the support they need to achieve their dreams.”

Rodriguez quit last year because multiple teaching positions went unfilled in her building while basic material and building needs went unaddressed and grievances ignored, she said: “You left me and many others just like me no choice but to seek employment elsewhere.”

MEA member Dena Ashworth testified she was the only certified math teacher left at the grades 7-12 building where she works, Accelerated Learning Academy. “I’ve given my life to Flint Community Schools and the children,” she said in a voice crackling with emotion.

“I’ve given you my love through the children. If I left this building, you would have no one certified to teach them math. Give us our steps. We are the reason this district is still here.”

Listening to Ashworth in the audience, Qiana Harden wept. A lifelong Flint resident, a product of Flint schools, and the field assistant in MEA’s Flint office for 18 years, Harden was moved by the speakers’ bravery and love.

At the next board meeting, Harden felt “compelled” to join others from the community speaking to the board. She’s never forgotten her teachers, she testified, naming and describing several without whom, “I would not be standing before you today.” Yet they have faced “deplorable” conditions, she added.

“Teachers have such an impact and influence on a kid’s life – even 40-plus years later… I keep thinking, what about the kids? The students. How can the board of education be looking out for the best interests of the students when you are not looking out for the teachers?”

A turning point came on March 13, weeks into the standoff. That morning 119 teachers called in sick, canceling school, and later in the day – two hours ahead of a school board meeting – the union held a press conference to announce a strike had been authorized by a near-unanimous vote.

In a room filled with UTF members and news media, Christian calmly but firmly delivered the message: “We must act for the sake of our students. We must act for the sake of our schools. We must act for the sake of our community. The time is now.”

The union had already put up billboards across town. Vice President Trishanda Williams said the same message echoed in every action: “What are you doing to increase salaries to retain and attract people? Without teachers, you don’t have a district.”

Meanwhile, a post critical of the teachers’ sickout on the school district’s Facebook page got backlash as hundreds of comments lit up with support for the educators. “Six-hundred or so comments on that post, and they were all positive for the teachers,” Williams said. “That felt good.”

Meanwhile, a post critical of the teachers’ sickout on the school district’s Facebook page got backlash as hundreds of comments lit up with support for the educators. “Six-hundred or so comments on that post, and they were all positive for the teachers,” Williams said. “That felt good.”

Soon negotiation dates were scheduled, and hours of bargaining led to a tentative agreement within two weeks, which was easily ratified.

Ironically on the same day, March 13, a little-noticed University of Michigan study published in the journal Science Advances shed some light on the suffering and struggle of children amid the Flint water crisis over the same 10 years as Flint teachers labored for concessionary pay.

The study found math achievement decreased and special needs classifications increased after the state switched the city’s drinking water supply in 2014 without ensuring the proper controls were in place to prevent lead contamination – leading to a federal disaster declaration for the city.

But while the UM study found “substantial negative effects” among Flint students, those changes occurred both among children who lived in homes with lead pipes and those without – suggesting more encompassing potential causes in addition to lead ingestion.

In other words, the water crisis affected all Flint children – not only those who experienced elevated lead exposure – just as the COVID-19 pandemic affected all children even if they didn’t contract the virus and more so in already stressed, high-poverty areas, the study said.

“Our results point toward the broad negative effects of the (water) crisis on children and suggest that existing estimates may substantially underestimate the overall societal cost of the crisis,” the study’s authors concluded.

The Flint water crisis is why teachers accepted a 19% pay cut back then – to avoid a threatened state takeover of schools by emergency managers charged with slashing budgets, a favorite policy move of Gov. Rick Snyder and the Republican-controlled state legislature with calamitous results for Flint and other majority-Black cities.

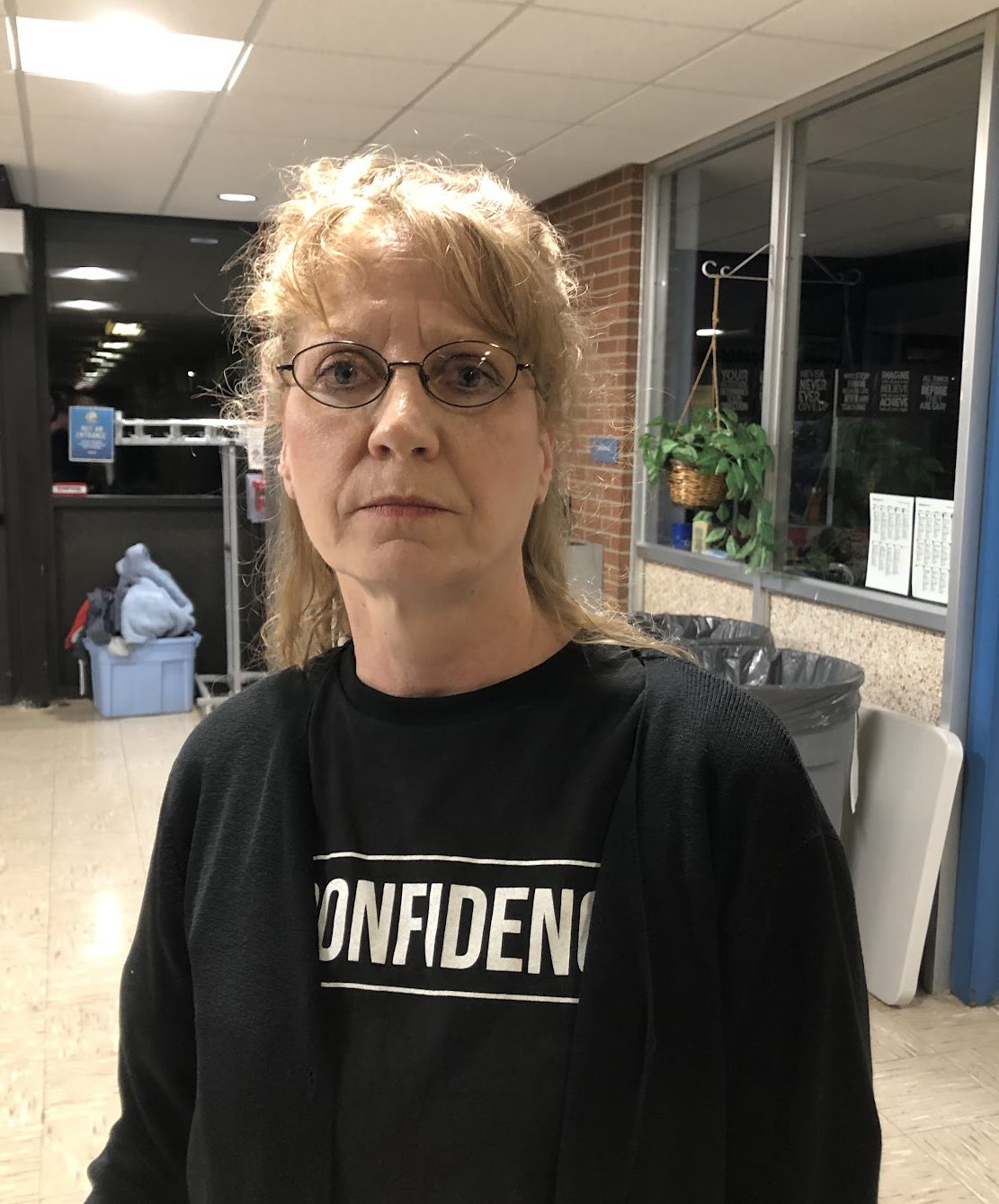

Hope is alive in Flint schools because of the settlement agreement, says Sherry Mockles, a longtime teacher and MEA member who had been “broken-hearted” over the past decade’s loss of veteran educators and dearth of enthusiastic newcomers replacing them.

“But I’m so excited for what’s going to happen now,” Mockles said in an interview.

A former middle and high school social studies teacher who now serves as an instructional technology coach in the district, Mockles said Flint has a proud tradition of excellence still reverberating in the community despite losses of students, teachers and programs across decades.

“I’d put our Flint students and teachers up against any district in the state,” she said.

Yet when she hired into Flint in the mid-1990s, the district had 30,000 students. Now it has 3,000 – the result of manufacturing job losses, charter school proliferation, and “the domino effect” of budget cuts leading to more student losses.

Over the past few years, the district combined federal COVID-relief money and private foundation grants to make $100 million in renovations to several schools with hope to build a badly needed new high school in the near future.

Next the district is planning what to do with vacant buildings and property, which became a point of contention in the battle over restoring teachers’ steps, the superintendent said, adding that this summer an aggressive enrollment campaign would seek to “bring our Flint scholars home.”

In addition to building renovations, state and federal COVID funds have been leveraged to make Flint a two-to-one technology district in which students have one device at school and one at home, Mockles said. Her job is to help educators use tech to expand and deepen student learning.

“No amount of technology, no amount of new buildings will save us if we can’t keep the staff we have and get new talent coming through our doors, but I’m really hopeful now it’s going to happen,” Mockles added.

For her part, Dena Ashworth plans to stay. After testifying she was the only certified math teacher left in her building, the 26-year veteran jumped from step nine to 15 and saw a five-figure increase in pay through the settlement – a sweeping life change that left her feeling “excited, relieved, valued.”

“I can breathe a little easier, maybe get some better food on the table, go on a vacation, fix some things around the house,” Ashworth said. “Our leaders rocked this. I can’t thank Karen Christian and Bruce Jordan enough; they brought us together, and it was beautiful.”

Christian also plans to stay a few more years and then retire with the hope this superintendent – her 24th in 33 years – can continue to lead the district toward a brighter day. The two sides will bargain a new contract in 2025.

Christian just got elected to another two years as president. She finishes 10 years on cancer medication in November. She’s four years out from a near-death experience with COVID that put everything in perspective.

“I finally feel like it’s OK for me to retire and think about other things I want to do in my life,” Christian said. “I know I’ll be leaving this in good hands.”