Creativity points to passion, purpose: ‘Art is how I dealt with grief’

By Brenda Ortega

MEA Voice Editor

Big themes recur throughout the story of Grand Rapids art teacher Stephen Smith.

Trauma. Grief. Hopelessness. Then creation, connection, community. Images and ideas return like motifs in Smith’s remarkable personal narrative.

A 37-year-old San Francisco native, Smith is a multi-faceted and award-winning artist, innovative entrepreneur, emerging community leader—and a second-year high school teacher who took what he calls “a backwards mode” into the classroom.

Painful tragedies dramatically altered his life course in college—away from computer science into psychology—and pointed him toward a future in art and education. In grief, he discovered art could be a healer, teacher, guide, path.

Now he shows young people the way. “The biggest problem I see in our inner-city youth—what I attack—is hopelessness,” he says.

“When people think there’s nothing they can do, there’s no option, that prompts the mind to have nihilistic tendencies, and nihilism causes people to live on the edge, take a lot of risk, do things they wouldn’t have done had they had something to lose.”

His mission is to show young people their value by tapping into what matters to them. “The first activity I do with all the students I have is we find where their purpose meets their passion. Then we try to live there.”

That’s where Smith lives with his wife Taylor and their three sons, ages two, four and six. The couple partners on numerous artistic endeavors, collaborations, and mentorships—always with more in the works, always aimed at expanding artistic expression and opportunities in Grand Rapids.

At the center of it all is Muse GR, an art gallery the pair created from a rundown building in the city’s West Side, previously an adult bookstore. The Smiths gutted and rebuilt the structure to house an art studio and exhibition space —now an integral part of the region’s arts scene.

Since its opening in 2018, Muse has officially hosted two juried winners at ArtPrize—the celebrated international art competition exhibited each fall in dozens of venues across downtown Grand Rapids—including Smith’s brainchild, “Art Pod,” which won one of six $10,000 awards in 2021.

In addition, he was one of 20 artists who collaborated on the Trauma Project, led by well-known local artist Scoob, which was selected last September as the 2024 ArtPrize winner of the $50,000 Juried Grand Prize.

The project—16 paintings by Scoob and an 18-track album by various contributors including Smith—first debuted at Muse in the spring before entering the competition at a different location last fall.

Smith also mentors aspiring young artists at his gallery’s studio. Some have contributed to winning ArtPrize entries, and a student of his from Ottawa Hills High School who creates in the Muse studio won the 2024 ArtPrize-related Consumers Energy SmartArt award and a $2,000 prize.

Smith also mentors aspiring young artists at his gallery’s studio. Some have contributed to winning ArtPrize entries, and a student of his from Ottawa Hills High School who creates in the Muse studio won the 2024 ArtPrize-related Consumers Energy SmartArt award and a $2,000 prize.

He can be outgoing and enjoys connecting with others, says wife Taylor. But he also feels deeply and can be a quiet and reflective thinker and problem solver. His next big dream is to fund a residency for a professional artist to live rent-free in the apartment above the gallery and get paid to create.

“Stephen is a creative in every aspect of the word,” Taylor said. “He’s influential, and he takes that really seriously. He knows that what he says and what he does is seen by other people, and he wants the impact to be positive, so socially responsible is what I use to describe him.”

A musician, photographer, composer, painter and mixed-media artist who loves to tell stories with his art, Smith is relentlessly creative—continually developing, planning, and executing new ideas.

He says, “When I leave the world, I want to be empty.”

‘Pretty little mistakes’

Just six miles from Muse, Smith is an MEA member teaching art foundations, digital media, and yearbook at Ottawa Hills in Grand Rapids Public Schools (GRPS)—and grateful to have landed in an ideal spot for his first full-time teaching job.

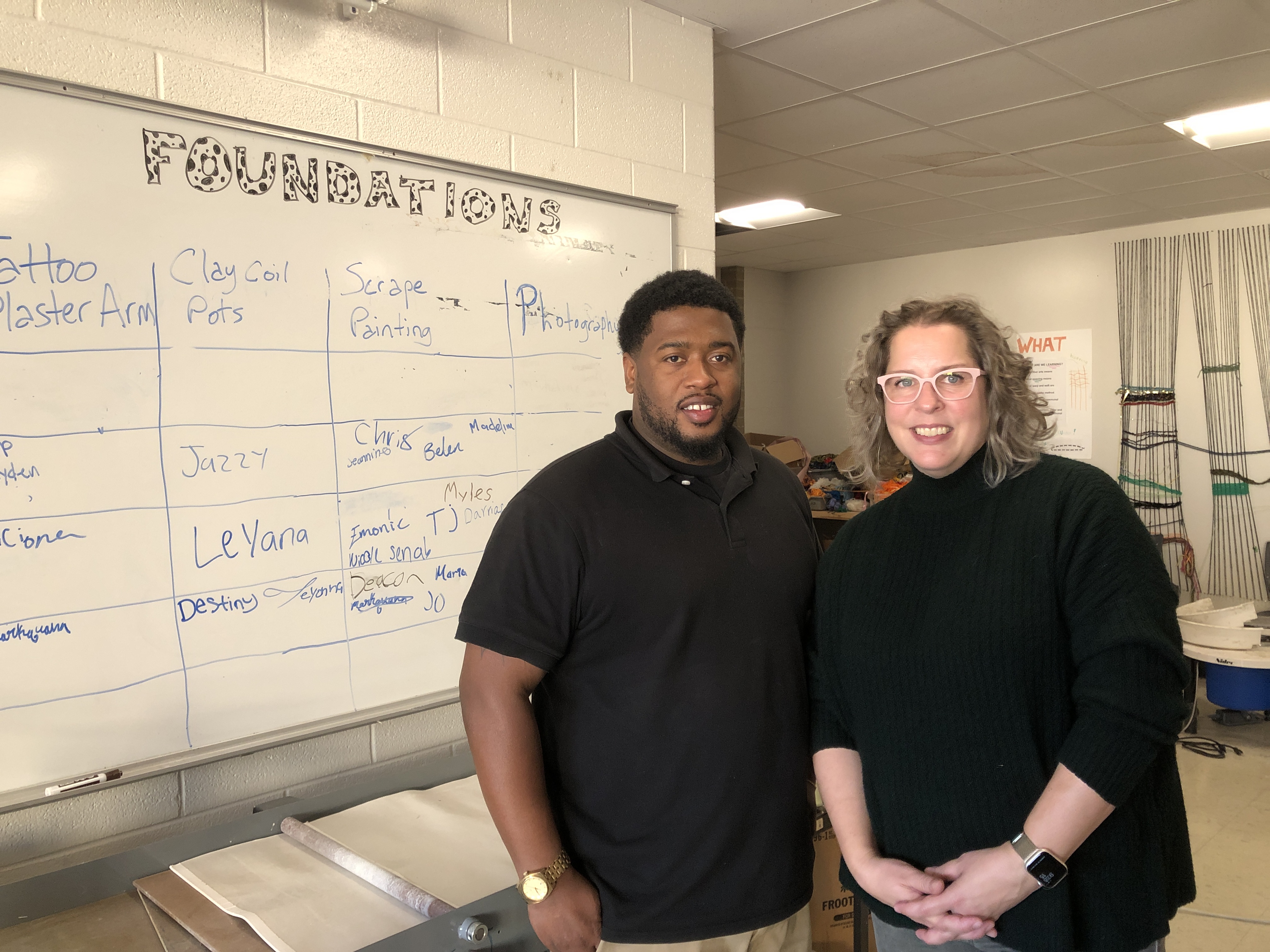

His classroom is joined with another art teacher’s space plus a versatile third room, and the two educators co-teach to give students greater choice in what projects to pursue and which medium to try.

“We partner the whole year,” he said. “We give students the options of two 2-D projects and two 3-D projects so they can go to either teacher. I’m focusing on 2-D; she focuses on 3-D. It’s been highly supportive for me to have half of my lesson plans created and we combine our efforts.”

His co-teacher is a career changer with an accomplished resume of her own. MEA member Jennifer Sharp previously worked as an award-winning digital creative director at National Public Radio, Public Broadcasting System, and Michigan State University.

Sharp has only one year more experience at the school than Smith, but in a short time she has repurposed corners and closets—and secured one-time federal COVID-19 funds from the district—to add a glass studio, three state-of-the art Macs stocked with Adobe suite, and a 3-D printer.

Those capabilities brought depth and variety to existing resources for drawing, painting, sculpting, photography and fashion design.

“To have this ability to offer choice and have student voice come through is really important,” Sharp said. “They feel ownership of the time they spend in the classroom, and it’s very exciting.”

Sharp feels “blessed” to work alongside Smith, she added. “What’s great about his perspective is that he can talk about real-life art careers and say from experience, ‘Your creative ideas are worth something; they’re valuable.’ And the kids believe and respond.”

A chart on a white board indicates how many students can sign up for each option.

“I like the experimental aspect of art class,” Smith said. “I feel like everybody has something that they will enjoy, so I expose them to different activities and processes. I prompt them to try things that will make them more comfortable.”

He likes to free inexperienced artists from anxiety by pointing out “pretty little mistakes” that can be the rewards of creative risk-taking. “You can run with a mistake or you can layer it,” Smith said.

On the flip side, Smith said obliteration as a strategy can also stretch comfortable artists out of their comfort zone—as in a fascinating communal art project that he and Sharp tried last year. The week-long prompting exercise utilizes pencil, charcoal, pastels and paints.

Students are given direction at each step. For example, they might be told to pick a word that describes a feeling and write it backwards. Add your interpretation of a flower. Place an image of an eye somewhere. One day they use pencil; then charcoal; then paint or pastel.

“We have them add things until they feel comfortable with it; then we say ‘Switch’ and tell them something to add to somebody else’s work,” he said. “The most anxious part is the obliteration where we tell them, ‘Now take white paint and go over it.’”

After the paint dries, the artists continue adding layers as directed until eventually out of messy chaos—despite their uncertainty—beauty emerges. “They loved them. It was really cool.”

He knows not everyone will become an artist, but exploring creativity opens up anyone’s potential. “One of my goals is 100% participation, so having students find their purpose and passion is a key in how I equip them to learn.”

He likes to frame students’ work, and he rotates gallery-style wall displays of student creations mixed with pieces by professional artists, which he also uses to teach art analysis: describe, interpret, judge.

One time he intervened with a student who wanted to throw away his artwork because it looked different from others. “I said, ‘This looks like fine art. Let me frame it and show you.’ When I framed it he was like, ‘Oh my gosh, it looks so good.’”

The dream center

Smith’s transition to leading a classroom has been eased by the fact he isn’t new to GRPS. He began his career in the district 14 years ago as a behavioral specialist, working with struggling students one-on-one or in small groups to help them better engage in school.

Back then too, he landed in a perfect spot at Martin Luther King Jr. Leadership Academy, a K-8 school where he had his own room dubbed “Mr. Smith’s Dream Center” where he managed a challenging caseload of students showing disruptive behaviors.

Smith extended access to creative activities they enjoyed doing in the dream center as they achieved steps toward a behavioral or academic goal. Drawing and painting. Writing songs or stories. Making a music video.

One girl’s behavioral turnaround was connected to her producing a podcast from a talk show she hosted before an audience. The girl studied and practiced topics related to social-emotional wellness and shared her learning in interviews using restorative questioning.

The show gave her positive attention. Other kids wanted to be interviewed or in the audience, Smith said, “and she would say, ‘If you want to be on my show, you have to exhibit these behaviors.’”

Smith started as a behavioral specialist in 2011, soon after earning a bachelor’s degree in psychology from Fisk University, a historically Black college in Nashville, and moving to Grand Rapids.

Thomas Standifer was a teacher at MLK—now an elementary school principal in the district—and saw Smith’s potential early on. Standifer encouraged him to become a teacher.

“Mr. Smith built relationships that made kids want to come to school so they could be in that room and hang out with him,” Standifer said. “He helped them find what they were looking for within themselves.”

Although he’d always enjoyed art, Smith didn’t find the purpose inside himself until he was away at college, studying computers, and dual tragedies plunged him into devastating grief. Both of his brothers back home were murdered in separate violent incidents just one year apart.

Smith coped by immersing himself in art, especially creating music and performing. His music built a following; he was taking every photography class at Fisk; and he changed his major to psychology.

“I wanted to figure out what’s in the minds of inner-city youth, and that’s how I got the idea to create a space for people to use art as counseling.”

Smith enjoyed being a school behavioral specialist, but it was a lot of work for low hourly pay, he said. He picked up side gigs doing corporate photography for several big clients—work he still does today—and teaching introductory art as an adjunct instructor at Grand Valley State University.

He met Taylor at church, where both volunteered on creative projects. She has a broadcasting degree and videography experience from work in non-profit communications. They married in 2015, and the next year Taylor agreed to buy the dilapidated storefront instead of a traditional first home.

It took nearly two years to complete renovations to open the gallery and move into the upstairs apartment—at the same time their first child was born.

“Originally we thought of something more on the photography-videography side of things,” Taylor said. “But in the process of re-imagining the space and what this area of town needed, we decided on an art gallery. That shift felt more inclusive.

“We are not very one-dimensional, so this allows for all the pieces of who we are and what the community is.”

They lived in the apartment for two years as the gallery got up and running before moving into a home next door to Taylor’s mother in 2020, anticipating their second son’s arrival.

Smith took the Michigan teacher certification test and passed. The district hired him to teach in the 2023-24 school year while completing a certification program. Taylor left a full-time job to manage the gallery and teach art part-time.

Life was hectic but good. However, tragedy struck again.

Smith’s mother was diagnosed with a brain tumor, and he juggled frequent trips to San Francisco for months amid first-year classroom demands. “I’m feeling more settled now, but it’s been challenging for me, a tough transition.”

He spent most of last summer in California, helping his two sisters care for their mom until she passed away in August at age 64. Her funeral was on the Friday before the first day of school this year.

Smith returned to his family, faith, and foundation. “Art is how I originally dealt with grief,” he said. “Now being an art teacher is cool because I have a student whose mother is sick as well, and I’m able to show him how art can provide comfort and relief.

“Even if you’re not a quote-unquote ‘artist,’ you still can do creative things that allow you to escape your grief or deal with your trauma in a healthy way. For me, I’m trying to find balance. Balance with work, balance with family, and taking time when I need it.”

‘Multi-hyphenate talent’

The young people he mentors and teaches say Smith pushes them to think and see possibilities. Ottawa Hills junior Nusra Juma says plainly, “He came into my life and changed everything.”

Nusra immigrated to the U.S. with family as a refugee from the Democratic Republic of Congo five years ago, settling in Nevada as a sixth grader who spoke no English. “I didn’t even know how to greet people,” she said. “I learned to express myself through art.”

Nusra bonded with a middle school art teacher, Ms. Wellman, who nurtured her talent over four years in Reno. When she and her family moved to Michigan last year, Nusra felt lost without her joy in painting. Then she was placed in art class with Smith, who recognized her gifts.

“He told me that he had a gallery that I could also use as a studio space,” Nusra said. “And now he teaches me new ways of art, how to sell my art. He provides most of the materials and sponsors my shows. I’m not the only one he helps. He’s simply a great person, so I can only thank him.”

Last spring, after Nusra created mixed-media sculptures as part of an in-class assignment, Smith suggested she find a way to adapt the works and enter the SmartArt (Students Making Art with a Renewable Theme) competition led by Consumers Energy, ArtPrize and GRPS.

Nusra won the district-wide competition for her entry “Earth Balance,” featuring a paper mache globe sprouting a vibrant tree. She was awarded a laptop, the $2,000 prize and public display of her work.

Nusra plans to pursue an art career and knows she can always lean on her mentor. “Mr. Smith is humble. He’s kind. He’s very talented and generous. There isn’t a bad word to describe him.”

Musician Tyrell J sings the same tune. At age 18, after graduating from GRPS, Tyrell got connected to Smith in 2020 via The Collective, a grant-funded program at Muse that offered skills-building and mentorship for a small group of aspiring musicians in Grand Rapids.

The Collective provided sanctuary during the pandemic, Tyrell said. “We were a family, always together. Even when we got days off, we used to ask Steve like, ‘Hey, can we come to the studio?’”

The group learned through workshops organized by Smith, wrote and recorded music, produced an album and video, and performed in local venues. Smith pulled back the veil from the business side of music and built their confidence, Tyrell said.

“Steve made big things seem small and doable if you’re willing to put in the work. He was always doing things behind the scenes. I didn’t know how much until later, but he was opening doors.”

Now 23, Tyrell J is an R&B and hip-hop artist who performs locally, including recently as an opener for a nationally known artist.

“One thing about Stephen—he does what he promises. He’s come to my events, sponsored some of my (album) release parties. He gave us photo shoots so we could have professional pictures. He is a multi-hyphenate talent, and I don’t feel like I can ever pay him back for what he’s instilled in me.”

The Collective was formed from a $10,000 grant awarded to the non-profit arm of Muse by the city’s SAFE Task Force, an anti-violence initiative. The planned one-year program stretched into three years, and “it’s a mentorship that’s lifelong,” Smith said.

Smith has broad connections in the arts community, which he calls on to support others. When he holds exhibitions of student work, the art creators, curators, and collectors he knows show up to buy it.

The same goes for professionals he showcases. Last year, Muse hosted two indoor solo exhibitions by well-known Michigan artists for ArtPrize. Both muralists and mixed-media artists, Sheefy McFly from Detroit and Pauly M. Everett from Flint, sold at least $20,000 of work at Muse.

A third exhibit outside of Muse won a $15,000 visibility award for Flint artist Keyon Lovett. Housed in a storage container that Smith converted to a mobile art gallery, “456: A Reflection on Fatherhood” recreated Lovett’s childhood living room with 456 letters to his father taped to walls.

The mobile gallery known as “Art Pod” first won a juried award for Smith in 2021 when he exhibited different artwork for each day of ArtPrize, including student pieces. Recently the Art Pod traveled to show Lovett’s work at University of Michigan-Flint.

Smith also contributed a song—“Cursed Generations”—to the 2024 Juried Grand Prize winner, the Trauma Project, a “three-part story” that moves from darkness to light. Muse debuted that work in four live activations last spring; now Smith is selling the paintings and developing a traveling exhibit.

The local artist behind the Trauma Project, Scoob, worked tirelessly forming community and energy around the work, Smith said: “People were flocking to the 106 Gallery to see it.”

‘The spark is hope’

One year ago, in the midst of Smith’s mother’s illness, the community also turned out to the Grand Rapids Public Museum to support a project close to his heart: release of an album by Smith and others, “God’s Gumbo” by Friends of Sinners, presented with an interactive “artscape.”

The sold-out event at the Chaffee Planetarium featured artifacts from the Grand Rapids African American Museum & Archives, southern cuisine by master chef Patria from Patria’s Kitchen, and the album’s music alongside images projected on the planetarium sky highlighting Black experience through a social justice lens.

The evening concluded with a tender tribute to Smith’s mother. Accompanying family images on screen, Smith’s emotional variation on the gospel song “Goin’ up Yonder” was rewritten to include personal messages with church choir-style backing vocals.

The album project was four years in the making, starting in the pandemic, so “The music expressed grief in a sense, but I was intentional about using it to uplift people.”

Because the Smiths are involved in many civic arts initiatives, including the Grand River Public Art Plan and the city’s Arts Advisory Council, they take care not to over-extend. Both must agree before starting a project, and sometimes the timing isn’t right… yet.

But as Smith sees it, a dream that takes shape makes the next one possible. Creativity is both its own reward and the seed of another. “Once you’re working in your purpose, hopelessness can’t exist,” he says.

“In the midst of feeling you don’t have a voice or you’re not being heard, you can create something that impacts people. There’s a spark that happens when other people light up at something you’ve done. The spark can give you energy to keep going. That spark is hope.”