Award winner changes lives and longs to thank educator who saved him long ago

EDITOR’S NOTE: We are saddened to share news of the passing of Juwan Willis on Jan. 2, and we send deepest condolences to his family, friends, colleagues and students. View Juwan’s obituary where you can also share a tribute or memory with the family.

By Brenda Ortega

MEA Voice Editor

Juwan Willis is a man on more than one mission.

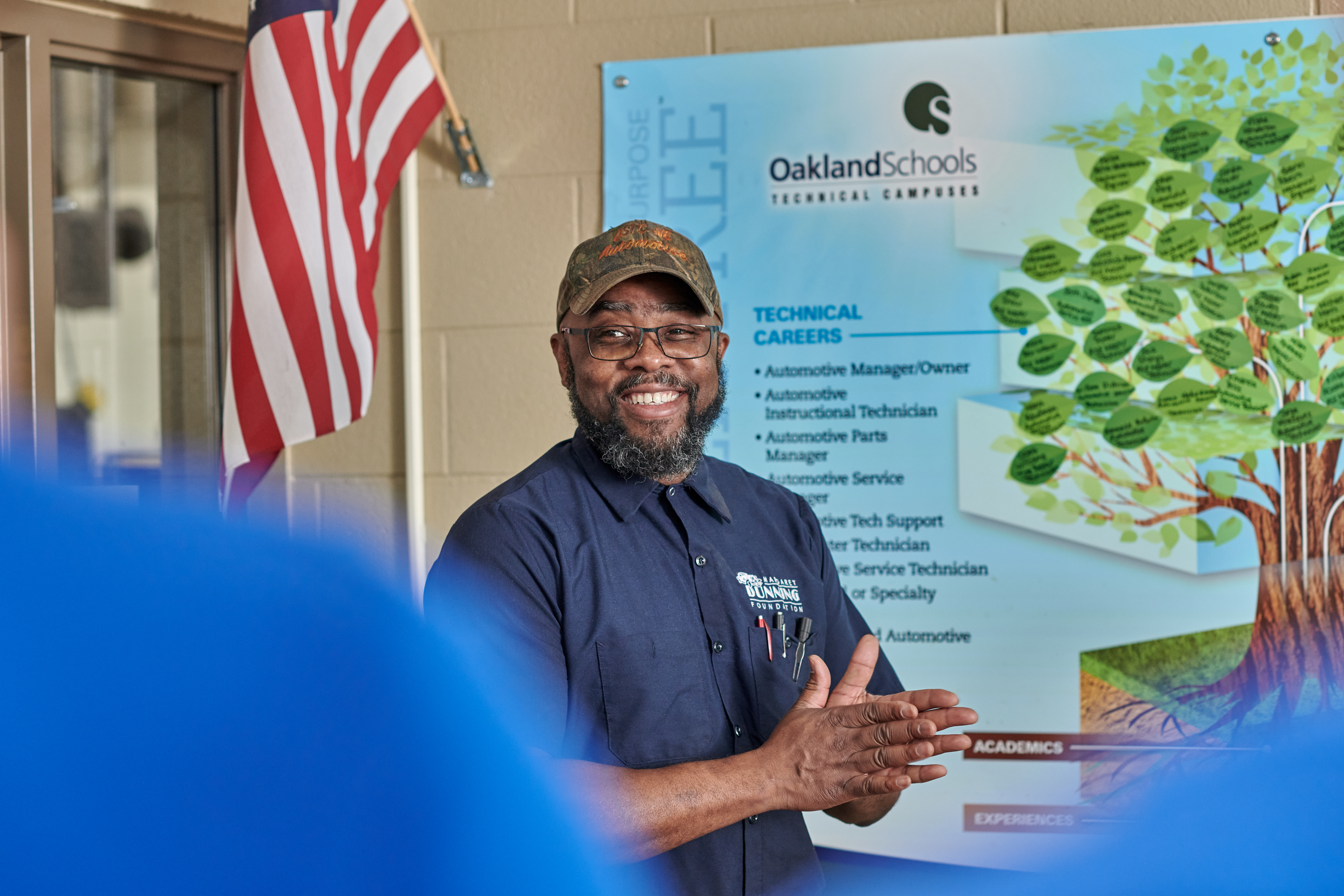

The primary pursuit that occupies the MEA member’s days is his goal to build the best high school automotive program in the nation at Oakland Schools Technical Campus Northeast (OSTC-NE) in Pontiac, where he aspires to do life-changing work as an educator. He is already far along the way.

Willis has won two national awards in an 11-month span. Last year in November, he was named the Byrl Shoemaker Instructor of the Year by the National Institute for Automotive Service Excellence (ASE) Education Foundation for his work guiding and motivating students to high achievement.

Then in October, Willis was named a $100,000 Grand Prize Winner of the Harbor Freight Tools for Schools 2023 Prize for Teaching Excellence. Of that award, $70,000 goes to his program and $30,000 goes to him.

He is not comfortable with the accolades, but the General Motors Certified World-Class Technician with 32 years of industry experience – including managing an auto dealership service department – hopes the attention will help to further his students and the program he’s built since 2012.

A former high school dropout and lifelong Flint resident, Willis could make $50,000 more annually starting tomorrow if he returned to work in the field, but he said in a wide-ranging interview, “All I care about at this stage of my life is my desire to pay it forward.”

Therein lies the second mission that animates his 50-year-old spirit.

____

Willis dreams to find the Flint educator whose persistence lifted him from a traumatic upbringing, marked by poverty and his mother’s severe mental illness, toward the security of job skills and income needed to take guardianship of three younger siblings and eventually raise his own six children.

His longing to show the unknown teacher or guidance counselor that her labor of love was not in vain – and to thank her for sticking with him even when he considered her an “arch nemesis” – returns often amid conversation about his life and work.

“I have spent years trying to find her to say thank you to her or her family because this was 34 years ago now,” Willis said. “I cannot remember her name because I did not understand what she was doing at the time, but she got me to muddle through, get my (diploma), start college and pursue automotive. She said she could show me how to pay for college, and she was true to her word.”

If not for her Willis believes he would be dead, or in prison alongside his childhood best friend. “I don’t know how I could ever express my gratitude, but I would like the opportunity. And if she’s no longer here, I just feel like her family should know because I can’t be the only one.”

He wants to say that her relentless effort had ripple effects that will continue for generations. For example, his stability gave his younger sisters a lifeline to become nurses. A daughter is pursuing a PhD in psychology. Another daughter was in Madrid this fall on a study abroad program.

Then there are his students. Two who are part of a post-secondary opportunity that Willis designed and is piloting have surpassed all expectations – including their own – by embracing the program’s motto: “You’ve got to do more to get more.”

They achieved master- and world-class technician status at a very young age, and both now mentor younger people coming up through the program to believe they can also accomplish what many said couldn’t be done without many more years of experience.

Devin Bailey, a 23-year-old graduate from Avondale High School, never dreamed he would make a six-figure income at his age, but he’s already earned ASE Master Technician and GM World-Class status with 14 certifications.

Bailey recently bought his first home – with guidance from Willis on mortgages, money management and building credit. “He’s basically been that father figure I didn’t have growing up,” Bailey said in a phone interview.

Today Bailey is mentoring his third student from the program, and one he helped – Kenyon Knight – is the first- or second-youngest person ever to become an ASE Master Technician at age 18 years and nine months.

Two years later Knight is 20, working with Bailey at Matick Buick GMC in Southfield, and also mentoring others. He admits to not listening to Willis at first, years ago. He thought he would learn enough to do oil changes and move on, but Willis saw potential and urged him forward, Knight said.

“I failed three ASE tests pretty badly before he started giving me practice tests and test guides and coaching me, and pretty soon I started picking them off – passing them one by one – and he pushed me more and more. He believed in me and never gave up; he kept pushing me and helping me.”

Knight credits Willis for how far he’s come: He earns six figures doing bumper-to-bumper service and repair, while living with his parents and saving for the future. “Willis always says, ‘You deserve the credit; you did the work.’ But I’m very thankful to him and all my mentors.”

____

Willis coaches many students in the program’s professional track to ASE Independent Technician status after high school. But working post-graduation with Knight and Bailey is part of a plan he has developed since 2016 to offer a technical early college option, known as the Master Automotive Service Technology (MAST) track.

MAST is an advanced program to offer students a post-secondary curriculum, a concentration on gaining professional certifications, paid career and internship opportunities, industry sponsorship, and college credits toward a two-year degree. Knight earned an Associate’s degree in MAST.

The pandemic slowed the program’s growth, but this year eight new students are enrolled in the first year of the three-year MAST program. Not all are certain to finish. The demanding program requires time, dedication and hard work, Willis said. It adds summer coursework and experiences.

However, he ensures everyone has every opportunity by getting students from under-resourced backgrounds their own 48-inch tool box filled with tools and valued at $5,000 – which otherwise can be a barrier to entry into the profession.

To date, 45 tool boxes have been funded by the Margaret Dunning Foundation in Plymouth via a grant Willis authored, and they are distributed to qualified students in programs across the entire Oakland County service area, not just to Willis’ students at the Technical Campus Northeast.

Students earn the toolboxes to embark on internships and work experiences, and they keep them as they go off to begin careers. “Once they earn the key, there are no take-backs,” Willis said, adding the Dunning Foundation has also contributed to his MAST start-up, thanks to grant-writing help from his colleagues.

With the toolbox, students can earn up to $23,000 during a year of internships and work experience in 11th and 12th grades.

Willis won’t advance those who aren’t demonstrating the necessary work ethic or skills growth, and he will pull a student from an internship or work placement if he gets a complaint from a shop manager or mentor.

“Some people want the moon but they’re not willing to walk to the corner,” Willis said. “I’m transparent with them; the world can be theirs, but they have to reach out and grab it. At times getting fired or demoted is the reality check they need. I’d rather it happen during high school so they can reset and come back.”

He always gives them a chance to rebound. “I’m a high school dropout. If somebody freeze-framed me at 16, where would I be? So I always tell them, ‘Yesterday was yesterday. Today is today. What are you going to do today to create the tomorrow that you want?”

____

____

Willis experienced what he calls his own tough career “growth moment” as a young adult working in the service department at Al Serra Auto Plaza in Grand Blanc nearly 25 years ago. He had hired in under the elder Serra and transitioned to management by the son, Joe Serra, after the father’s death.

“Joe was very personal,” Willis said. “He used to throw picnics, take everybody out on their birthday to a restaurant across the street. But I had a chip on my shoulder.”

The only Black technician in the competitive shop, Willis was among the best certified and top earners when a new supervisor began to question his competence. He attributed the reason why to racism. When the manager told him to do something illogical, Willis launched a verbal assault, he says.

“I was extremely unprofessional. I yelled. I cursed. I said F-bomb you. You are a stupid idiot that doesn’t have common sense.”

Later he appealed to Joe Serra, and met with him to complain about the manager’s animus. “He stopped me and said, ‘But why did you act like that?’ My excuse was ‘He made me.’ And that’s the only time I’ve ever been cussed out by a multi-millionaire.”

Willis left without a job that day, believing he was unfairly blamed for the larger climate problem in the shop. Five years later, in a parenting moment, he heard himself telling his son not to be goaded by his sister into reactive behavior that will get him into trouble instead of her. An epiphany happened.

“I finally came to a full understanding of what happened. I was good marketing for (Joe Serra). I was a high wage-earner. He had invested in me, but I had done something in front of everybody that he couldn’t support.”

____

Willis shares the story and its epilogue with students in a PowerPoint introduction each year: how he rose to management at another dealership but then got the urge to teach and loved it after trying a temp job. How he hired into this Tech Campus in Pontiac which now feels like family.

How Joe Serra soon bought out a local dealership where Willis places interns, so he reached out to reconnect and ensure a continued strong partnership. “I think we’ve had nine students that graduated within the last five years at that dealership, so my story with Joe Serra came full circle.”

He holds frank classroom discussions on race, setting out clear expectations for respect and safety. He builds cohesion with t-shirts every student receives, printed with a flashy logo of a fist holding a tool, plus the “Do more to get more” motto and “OSTC-NE Automotive Co-Ed Fraternity.”

He believes part of the race divide in America comes from lack of exposure. “I was an inner-city kid out of Flint, and a lack of understanding about my culture applied to my co-workers, but I didn’t have experience with people from higher wealth either.

“Now I’m here and getting students from Rochester schools which are between 1 to 3% Black and from Pontiac next door which is between 1 to 3% white. I explain that some of these biases we have is because we haven’t learned anything different.”

Students may find themselves in a workplace where they’re the only person of their race, ethnicity, gender or age, and he tells them: Lean into it. Be your best, and own your status.

____

Willis heaps praise on a mentor who has helped him grow and learn as an educator. His principal at the Tech Campus, Paul Galbenski, in 2012 was named Michigan Teacher of the Year and remains the only Career and Technical Education (CTE) teacher to be awarded the honor.

The two became close working late into evenings with conversation in the empty building. Galbenski is a former longtime high school basketball coach – a role in which he also earned many honors – and “He’s a bullet-point guy, which is very contrary to me,” Willis said, laughing.

“I’ll get going talking about 18 different things. I’m a reach-for-the-stars guy, because I figure if you land on the moon you’re still getting paid better. But reaching for the stars is usually doing something that hasn’t been done. Paul gets me back to – Hold on. Step one; what are you going to do first?”

Willis was among his first hires when he was a new principal, Galbenski said in an interview. As a career changer, Willis articulated a vision from the outset and every year has reflected and provided more opportunities for students, Galbeski said.

“The proof is in the pudding. Now he’s been at this for X number of years, and those alum keep coming back that are now master techs and assisting with new techs. He’s instilled a pay-it-forward mentality, which is the type of support system that makes programs successful.”

With his life experience and industry expertise, Willis develops excellent rapport with young people and builds their “career-ready” skills of problem-solving, collaboration, communication and personal management, Galbenski added. “He’s very thoughtful in knowing how to move a young person from point A to point B if he can get them to trust the process.”

An inspiring “idea man,” Willis sometimes needs help with structuring and organizing a plan, Galbenski said. “I’m a teacher and coach at heart. This is all coaching. It’s all mentoring. That’s how I led basketball teams for 21 years—it’s about maximizing the talent you have on your team.”

____

Willis discovered since arriving at the Tech Campus that he is autistic. Before that, “I didn’t know all of my idiosyncrasies could be labeled,” he said.

His daughter the psychology major shared information after he recognized himself in the struggles of various students identified as autistic and found himself offering those students advice based on his own experiences.

It’s another life story he shares in the introductory PowerPoint with students. The “soft diagnosis” doesn’t change anything, just explains his quirks and coping strategies. For example, he wears his keys, wallet and other pocket items in the same place every day or else he feels “crooked.”

A fan of science fiction, including Star Wars and Star Trek, Willis uses that and a fascination with anime and animation to escape from stress, dating back to his troubled childhood. He loves Superman, because he says, “Superman’s restraint is the only reason Batman has ever got the best of him.”

He also doesn’t shy away from discussing his difficult youth as he gets to know students.

The eldest of six siblings, including a disabled younger brother who required total care, Willis didn’t meet his father until age 29. When his mother’s mental illness required her to stay in a psychiatric hospital for weeks or months at a time, the children moved in temporarily with their grandmother – a powerful family matriarch.

Her youngest son, Willis’ uncle, was also a strong influence. “I call him Uncle Daddy because he filled that role, and I picked up a lot of his habits.”

As a young child, Willis enjoyed attending the school by his grandmother’s house. But when his mother transferred him to a new building, he was bullied for the next few years. By middle school, he was skipping, and by high school he dropped out.

His mother taught him to drive at age 12, and at 14 Willis used the car to operate 10 newspaper routes with his siblings. He split the earnings with his mother and learned to fix the vehicle with how-to guides and parts from the auto store.

Then a house fire forced the family into low-income housing, which he compared to “fencing us in like a bunch of animals.” There he reconnected with friends from his first elementary school who were engaged in illegal activities.

But Willis had a car – if not a driver’s license – and decided to work at McDonald’s where he could also get free meals. His competitive nature kicked in, he says: “More hours meant more money and bigger meals. I was always willing to work harder if I could see a way to get something I wanted.”

That would lead to his first encounter with the mystery woman at Mott Adult High School. Willis showed up at age 16 to re-enroll at the alternative school so he could apply for a waiver allowing him to work 40 hours per week at McDonald’s.

She began checking in with him at work, and Willis feared she would cost him his job. She learned his backstory and encouraged him to pursue training in the automotive field. “She kept coming to check on me, coming to check on me. And I went from ‘I can’t stand this woman’ to ‘Where’s she at?’”

She had him visit Genesee Career Institute and later helped him navigate the financial aid system to begin courses at Mott Community College. He used that training to get entry-level jobs, earn money, support his family, and pay for more training to advance.

____

Willis supported 11 people at the time he was fired from the Al Serra dealership in his late 20s, including his mother and younger siblings, his wife and six children. Willis cared for his disabled brother until his death at age 41 a few years ago. He still helps his mother, now in assisted living.

It’s why his thoughts keep turning back to the teacher or counselor from the school who helped him find his way. “Were it not for this woman reaching me, I would not be where I am today. I raised all of these people, and I don’t have to be money-motivated anymore.”

He regularly gets job offers from shop managers hoping to lure him with money, but that isn’t what he wants, he said.

“A lot of those jobs are attractive, but I literally pass on making $50,000 more because I wouldn’t be able to accomplish my goal—which is to be a truly unforgettable educator that helps change somebody’s life, like what this woman did for me.”

_________________________________________________________________________________

Congrats! Michigan Tools for Schools Finalists

Two MEA member skilled trades instructors were among 20 finalists nationwide to win $50,000 in cash prizes in the Harbor Freight Tools for Schools 2023 Prize for Teaching Excellence.

Jeff Webb, an advanced manufacturing teacher at the Southern Michigan Center for Science and Industry in Hudson Schools, was named a finalist for the fifth year in a row. Formerly a middle school science teacher, Webb took on the role of teaching everything mechatronics five years ago.

Webb said of his work: “If my students choose to go directly into the workforce, the certifications they earn before graduating make them much more employable. If they choose to pursue higher education, the skills they’ve learned in our program are a springboard to advance quickly, or to earn good money and pay for their education.”

David Barresi, a carpentry teacher for 40 years, was awarded the finalist prize for his work teaching woodworking at Frankfort High School where his students have won numerous state- and national-level woodworking competitions.

An accomplished woodworker and furniture designer, Barresi said career readiness and vocational enrichment should be emphasized within all secondary education programs.

“Not only do we need to provide opportunities for all students, but from a societal need, we have to address the income disparity and vanishing skilled labor force. At this time, five tradesmen are retiring as one new tradesman comes into the profession.”