Kalamazoo support staff challenge exclusion from ‘educator’ bonuses

By Brenda Ortega

MEA Voice Editor

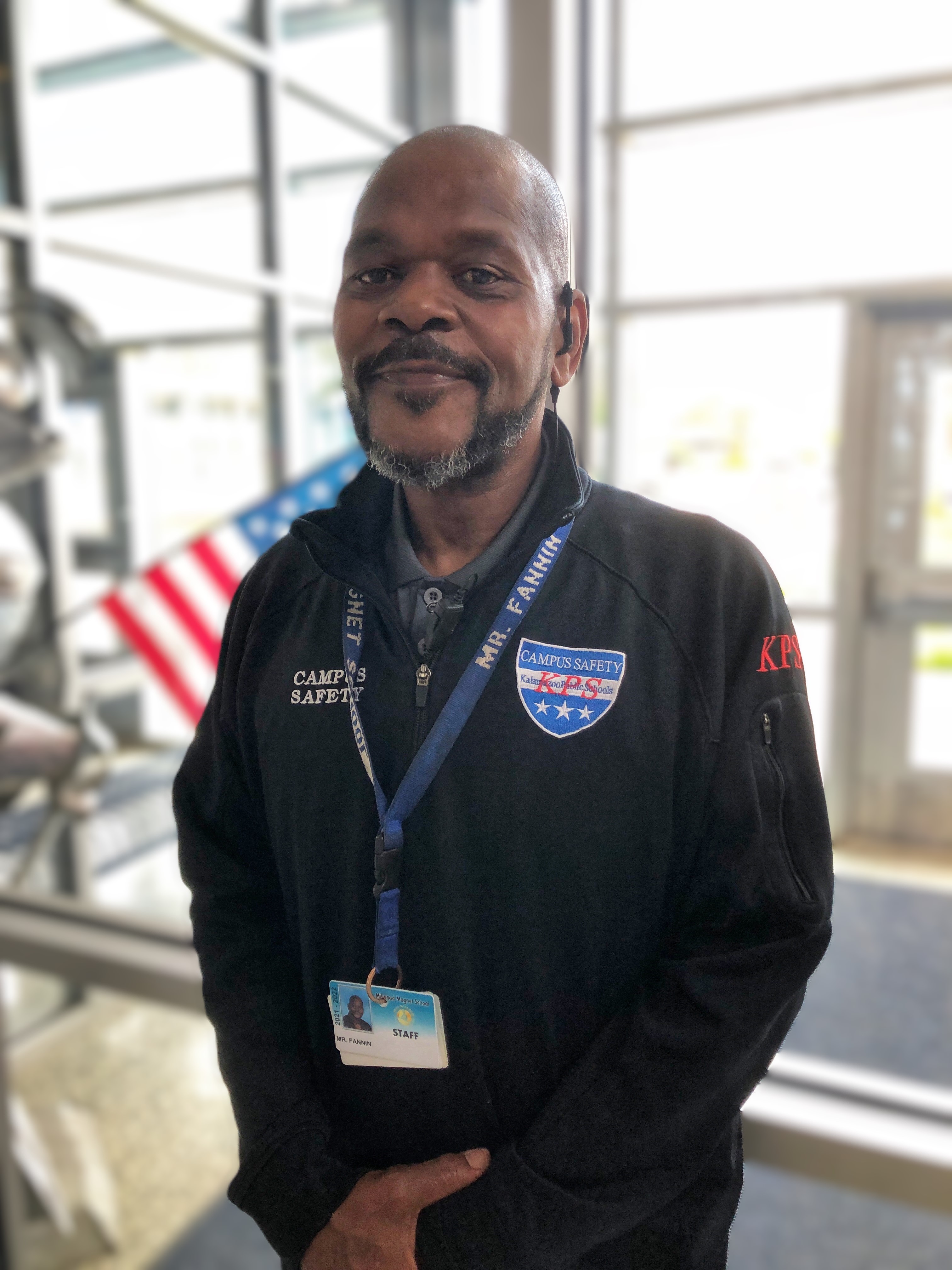

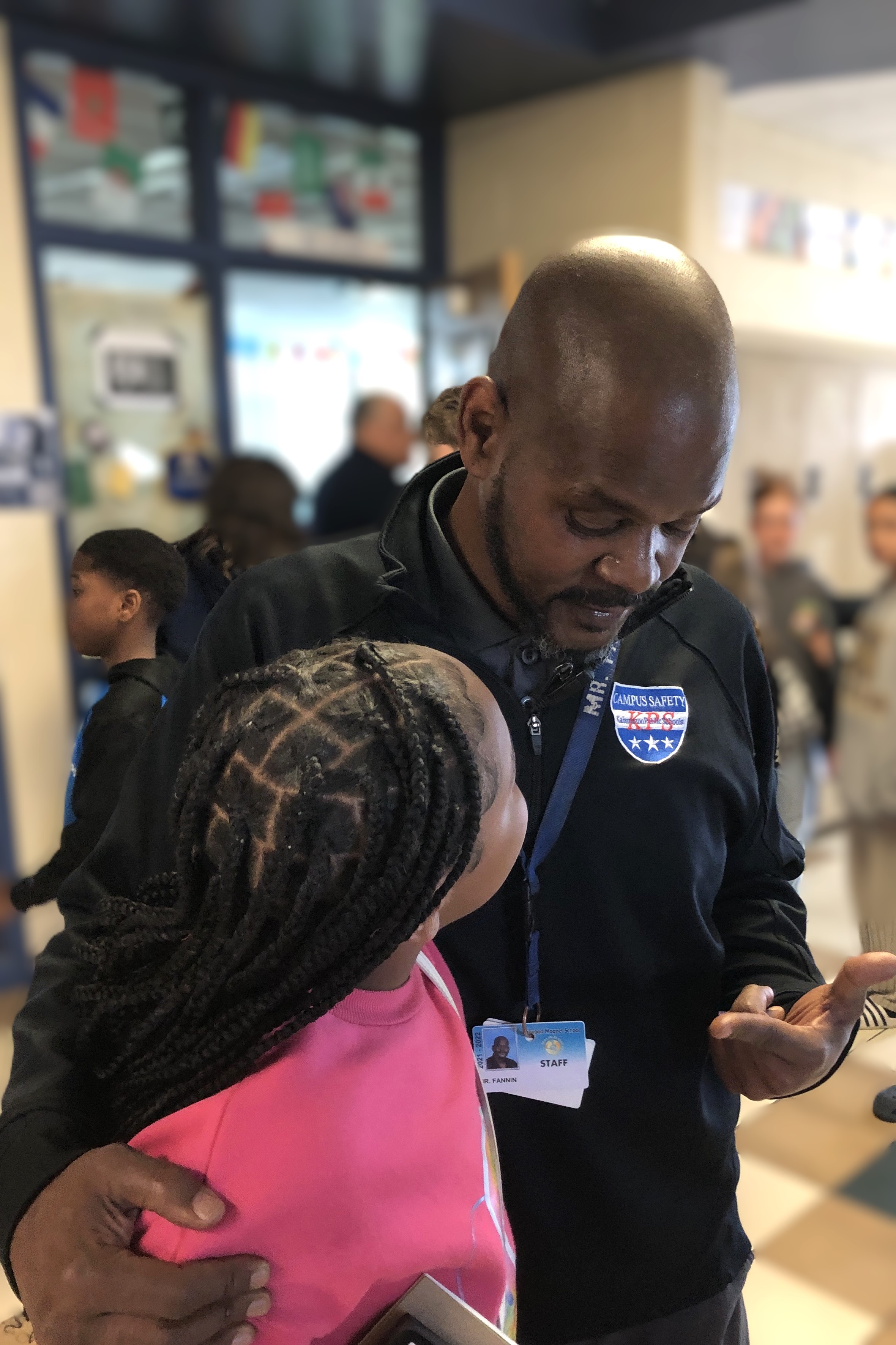

MEA member Kevin Fannin doesn’t need accolades to know he’s doing incredible work with young people at Milwood Magnet School in Kalamazoo—the looks on kids’ faces when they see him, the smiles, the hugs, the high fives, hand shakes and fist bumps say it all.

But as a longtime school employee serving in a vital supporting role, it would be nice to feel appreciated by central administration, he says.

Instead, support staff across the district who transport, care for, and protect children every day were not included in a district plan to use state grant funding to pay educator bonuses. They were told the reason for the omission was they don’t meet the definition of “educators.”

“The money’s not even the important thing, but I can’t believe that’s what they’re saying,” Fannin said. “I go through this building with 800 kids, and I meet every last one. I know their names; I get to know them and what they like. I communicate all day every day so I can build that rapport.”

The longest serving campus security guard in Kalamazoo Public Schools with more than 30 years on the job, including 20 years at Milwood, Fannin is beloved in the grades 6-8 building. Walk the hallways with him, and it’s apparent – not just from bright smiles and banter but comments from colleagues.

They will stop and tell you: He’s a rock star, a great guy, a wonderful person doing what he was meant to do. MEA member Amy Schrum, a special education teacher whose students adore Fannin, tracked us down in the cafeteria amid a busy lunch scene to make sure it was understood.

“He’s awesome, so good about checking in on my kids and escorting them where they need to go,” she told me. “He’s always happy, he always has energy. If he’s having a down day, he doesn’t portray that to the kids.”

Fannin has worked in the district so long that he knows parents and grandparents of students well enough to offer guidance and wield influence with families, added Principal William Hawkins.

“He’s an integral part of our learning environment who makes positive connections with students, their families, community members, his co-workers, bus drivers and everyone,” Hawkins said. “He actually helps to defuse difficult situations because of those positive relationships.”

Fannin never stops moving. Kids in crowded hallways change course to hug, handshake or high-five him. He chats with some walking by and stops others if teachers or bus drivers have shared concerns.

“Don’t you be doing that on the bus or I’ll be hearing about it!”

“I expect to get an A+ report when I check in.”

“Did you find your Chromebook?”

“How’s your sugar level? You let me know if you need me.”

He buys treats to reward students who volunteer for lunch cleanup. He breaks up fights, soothes hurt feelings, and convinces kids who’ve lost control of their emotions to follow him to a quiet location. He is the boys’ basketball coach at school and a youth league coach in the summer.

At age 57, he still lives in the house where he was born and has spent all of his life outside of four years in the military. It can be a tough neighborhood, so he pays several kids each summer to do errands such as yard work and returning cans and bottles to keep them busy and put a few dollars in their pockets.

His own four kids all graduated from Kalamazoo schools.

“I don’t mind I’m bottom of the totem pole – I like what I’m doing; the kids keep me going. Same way I do to them, they do to me. I make them smile and help them out when I can, because sometimes they don’t have nobody at home. You might never know what they’re going through.”

‘Kids still come see me’

The conflict over who should receive $500 educator bonuses has been hurtful across and beyond the membership of Kalamazoo Support Professionals (KSP), the union representing bus drivers, paraeducators, campus security and office staff, said KSP President Joanna Miller.

A nine-year bus driver in the district, even she has been hit hard by comments made about people who work in roles that do not involve direct classroom instruction yet contribute to the team effort required to educate children, Miller said.

“I hate to say it, but I’m used to having our concerns dismissed and having to fight for every single thing. And even so I’ve never been told I’m not an educator. I’ve never had it said so bluntly how unimportant I am in my job—when I absolutely love being a bus driver.”

Miller points out that she received formal training to operate the bus, but it’s thanks to the support of colleagues that she’s learned to manage a mobile classroom of 65 middle schoolers or 40 elementary students she’s responsible for delivering to school safe and sound and ready to learn.

“I’m following IEPs (Individualized Education Programs) and directions from teachers and paras about how to manage behaviors for my students who have autism and their safety plan for how they’re supposed to take care of things on the bus,” she said. “I report back and coordinate with folks on behavior plans.”

She learns names and gets to know kids – like the third grader she recently helped in turning around a sad morning – and now with nine years under her belt she recognizes the impact she makes being the first person to greet students in the morning and the last one to wave goodbye at the end of the day.

“I have an elementary school that only goes to third grade, and I’ve got kids in high school now that I drove when they were little that still come see me. They come find me because they want to tell me something that happened. They want me to enjoy their successes with them.”

Her driving colleagues have been similarly moved to testify at board meetings and write beautiful emails to the superintendent describing the love and care they bring to their work, Miller said. One longtime driver described the job as “magical,” she added, “and it reflected my story too.”

In discussions and meetings with Superintendent Darrin Slade – appointed to the top post in Kalamazoo one year ago after working as a teacher and principal in Maryland and Washington, D.C. – KSP has reached no resolution on the disputed educator bonuses.

The original plan for paying out the money included principals, but via their union those building administrators asked for bonuses to go instead toward lower-paid employees.

The support staff unit issued a demand to bargain over the compensation and will file an Unfair Labor Practice if negotiation is refused on a mandatory bargaining subject, said MEA UniServ Director Tom Greig, who has asked the school board to investigate and reverse the district’s stance on the bonuses.

In this year’s state budget, lawmakers allocated $68 million to go toward additional compensation for educators, and Kalamazoo has about $560,000 for the bonuses. The term “educator” was not defined in the legislation – either narrowly or otherwise – according to MEA Economist Tanner Delpier.

However, Slade said in a meeting he defined an educator as a teacher, Greig said. “This flies in the face of everything that we know it takes to educate a child,” Greig told the board.

Last year the KSP bargaining team fought hard in contract talks and won a good raise for the workers it represents, plus some paid time off for sick days and snow days, and other basic items such as district-bought uniforms.

After 10 years of little to no pay increases, improvements were needed to attract applicants for vacant positions after COVID, Miller said, but a long overdue bump in pay shouldn’t mean those employees don’t deserve a bonus or further hourly increases.

“We still don’t receive a living wage; it’s just better than it was. If I didn’t have a dual income, I’d be stuck.”

‘Kids are always learning’

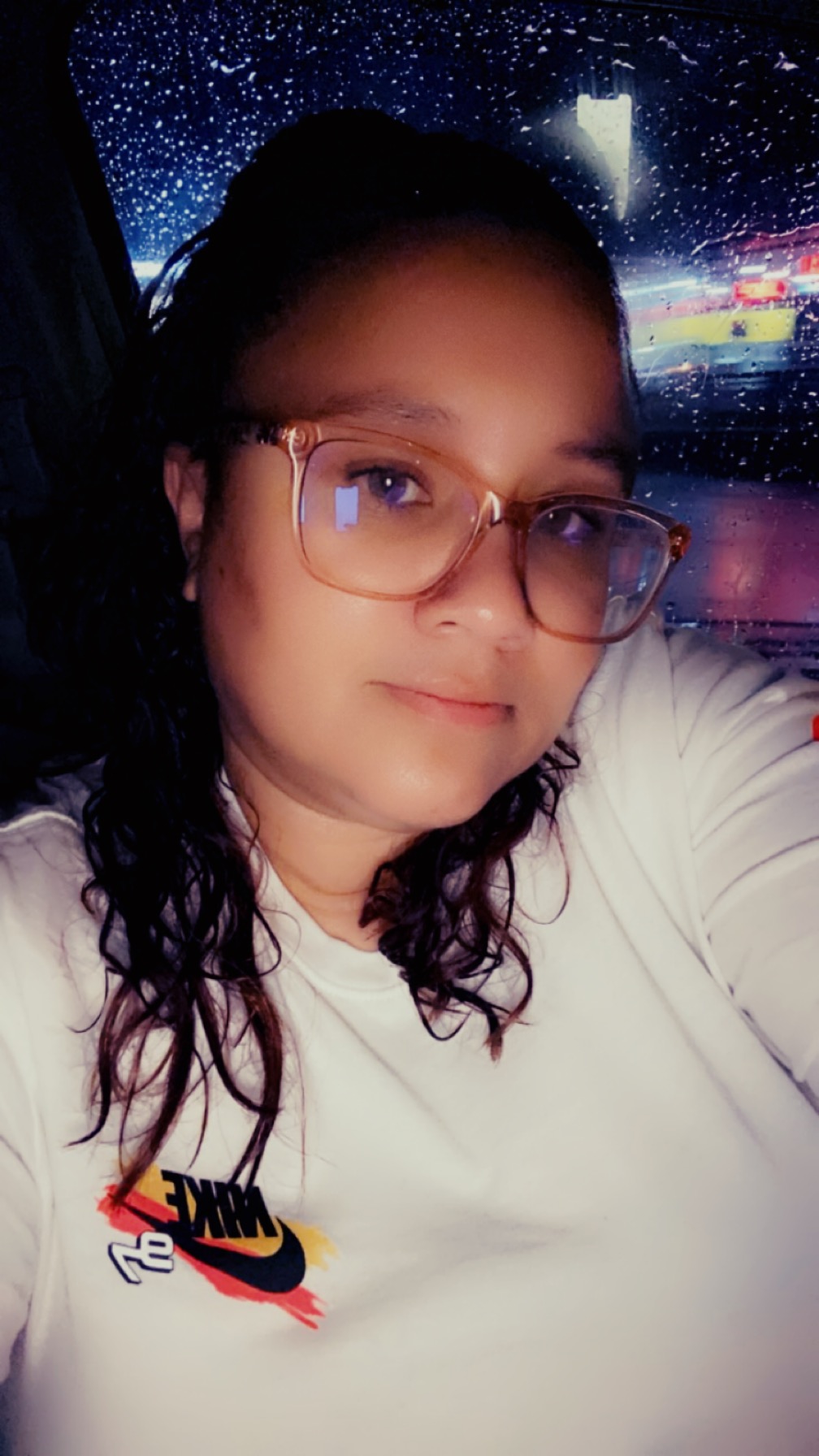

Someone who finds herself stuck in an “extremely hard” situation is Shona Espinoza, a nine-year employee of the district and KSP vice president who works as a special-education parapro at Hillside Middle School.

The single mom and grandmother is looking to move homes for the third time since February of last year. A new owner of the building where she lives is raising rent for a two-bedroom apartment by $400 to $1,300 a month.

“I was just meeting with somebody about housing, and they say you have to make three times the amount of rent to afford a place,” Espinoza said. “It’s a struggle to make just one times the amount of rent on top of being a single parent, on top of having other bills, on top of having to take care of your kids and groceries.”

The pay raise negotiated last year reduced the amount of food assistance she receives for her family. Meanwhile, she could make more money doing something else, but working with young people and watching them grow is wonderful: “It takes helping just one person to make you feel whole.”

Espinoza is assigned to work with special education students in a general-education classroom, but she assists any child who needs it “because to me that’s how it should be.”

She and the teacher she works with view each other as equals and co-teachers. “I help make lesson plans when needed. I help kids with their work and collect their work. I pull kids to test or I sit in the classroom and do assessments. I sub as the teacher in classes. I deal with behaviors.”

Like so many educators, she serves as an impromptu social worker when she encounters students and families struggling with external issues that affect kids’ ability to learn – connecting them with counseling services, mentors, assistance finding food, diapers, clothes, “anything you can think of.”

The district’s plan for paying the bonuses includes paraeducators like her, but Espinoza has been testifying at board meetings and encouraging coworkers and community members to do the same because leaving out other people who do important work is “a slap in the face.

“It devalues who we are and what we do for these kids but also for this district. In reality, we all educate these kids in our own way, in different ways. There’s always a teachable moment. Kids are always learning.”

‘Walk in our shoes’

Districts could not function successfully without the labor of drivers, secretaries, cafeteria workers, paraeducators, custodial and maintenance staff, campus security, activity helpers, Title I tutors, and more, says MEA member Mrs. Prevo, lead administrative secretary at Spring Valley Elementary Center for Exploration.

Known only as Mrs. Prevo by students and adults alike, she has worked in the district for 16 years. Prevo recently attended a staff meeting where she heard the superintendent explain the bonuses saying he defines “educators” as teachers, and she was incredulous.

Her response was, “How can you say we’re not educators?”

She began documenting the many ways she has “constant interaction” with students in the main office: late arrival, bloody noses, illness, injuries on the playground, disruptive behavior, lost teeth, bleeding gums, concussions, asthma attacks, medication dispensing, help with homework, conflict resolution.

“How can someone say we’re not educators?” she asked again.

When students come to the office crying because someone called them a name, Prevo de-escalates by shifting their perspective to their true selves. “I talk with them and I ask them, ‘Are you really that name they called you? Don’t allow anyone to disturb your peace, because you are beautifully and wonderfully made.’

“I tell them, ‘Do not allow anything to get you off focus with getting the best education you can get. You are a queen (or you are a king).’ And they leave the office differently from when they came.”

That is one example of work she does throughout every day in addition to administrative tasks that keep school days functioning. “‘Huh? And we’re not educators?’”

Sometimes students approach Prevo frustrated with homework they don’t understand. Recently a youngster said he was giving up on math because he couldn’t understand multiplication. She showed him how to group and count out multiples by making marks on paper.

“I may not have a master’s degree, but I’m a daycare provider. I’m a counselor. I’m a teacher. I’m a parapro. I’m a child accounting secretary. I’m a nurse. I’m a pharmacist. I’m security. I’m wearing all these hats, and I do not understand how a person can lead in education and not see the importance of your support staff. Are we invisible?”

She welcomes students to share good news – behavior improvements they’ve made or something they learned in class – and rewards them with excitement, a hug, and treats she supplies herself. She even talks with parents at times to help them reinforce social, emotional and academic learning at home.

“I challenge every administrator to walk in our shoes for two weeks. Work in the office for two weeks. Serve in the kitchen. Be a custodian or a parapro. Drive a bus. We do important jobs, and it is challenging on a daily basis to do what we do.

“What would happen if none of us were present for a week? We deserve to be recognized and included, not excluded.”