The Evolution of Student Voice

By Jessyca Mathews

Carman-Ainsworth High School

“Ms. Mathews, why don’t we have Black History courses here?”

I’ve heard this question often over two decades of teaching. In fact I asked the same question as a student at the same building – Carman-Ainsworth High School (C-AHS) in Flint – where I now work.

For many years, I would answer kids by telling them to advocate for what they wanted to have in their educational spaces. Some kids thought it would be a lost cause because “adults in charge won’t change” and “too many people would get mad at that kind of class.”

More recently the students decided they couldn’t sit back and not speak out on classes they needed for their personal growth and expansion of their knowledge.

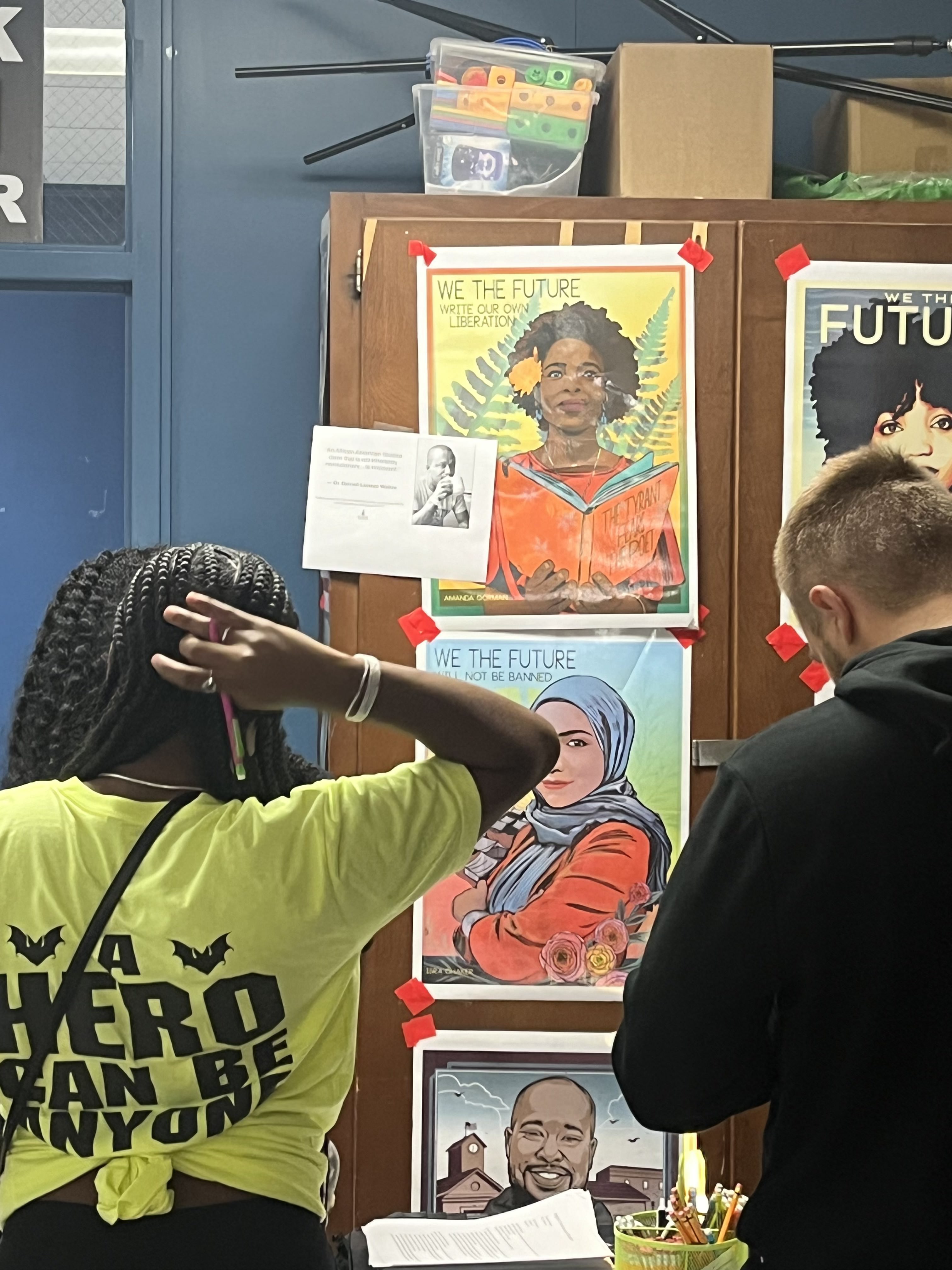

Some students wanted to learn about their racial history, while others wanted to learn about their African origins. Some ally students wanted to know true history so that they could tell others and be supportive toward their classmates. The kids knew what they wanted.

When I was approached by Tica Stinson, a C-AHS counselor and fellow MEA member who had done preliminary research into requirements for bringing the new Advanced Placement (AP) African American Studies course to our school, I couldn’t ignore this call to action.

As educators, we should always ask ourselves, “Are we truly listening to what our students need in schools?” and “Is true history being provided for our students?”

In a world filled with misunderstandings, misconceptions, and hate, we cannot allow fear to drive us out of our main responsibility for our students: creating leaders who will improve the world.

With these questions in mind, Tica Stinson and I embarked on a journey to introduce the course at C-AHS.

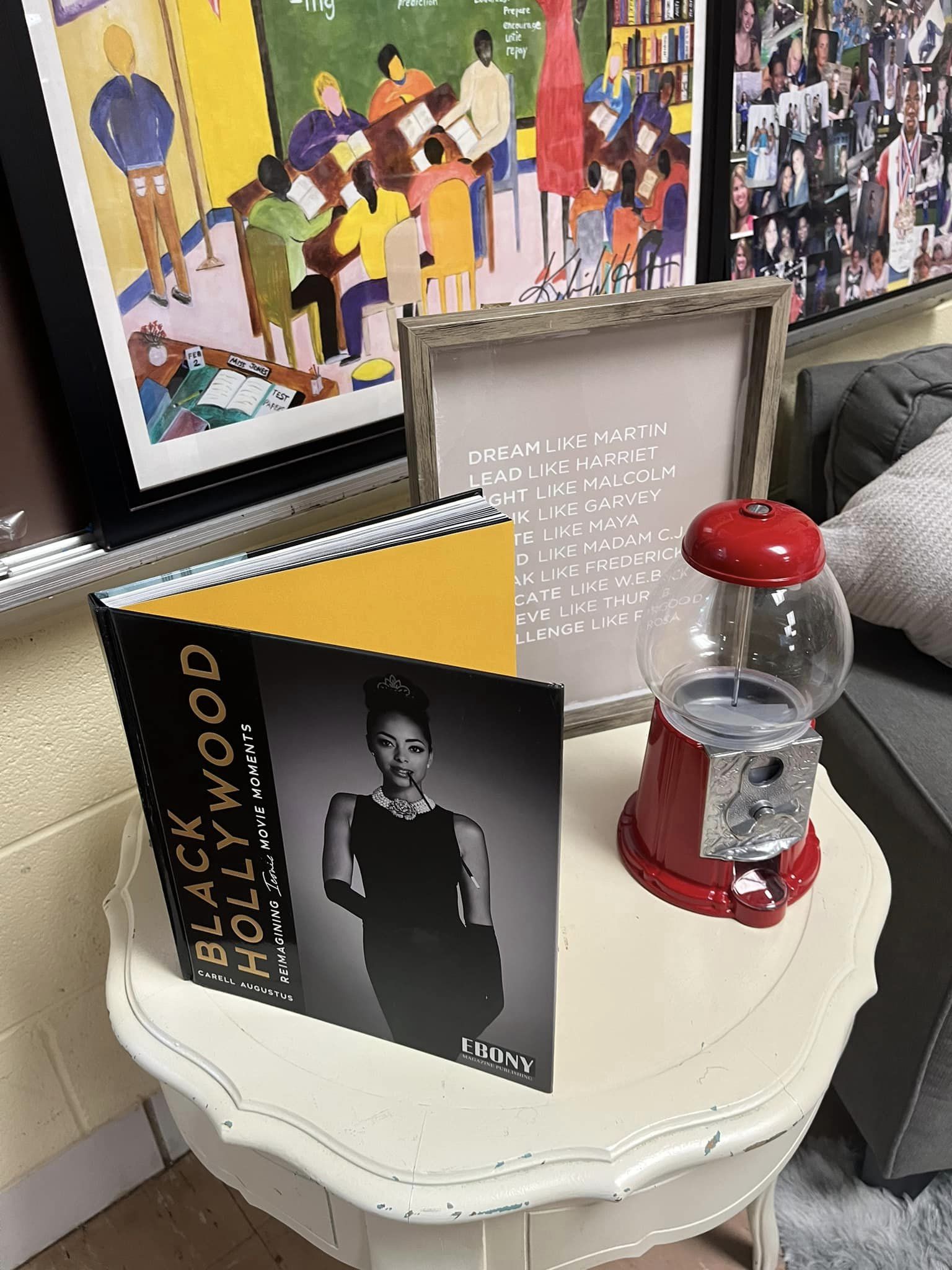

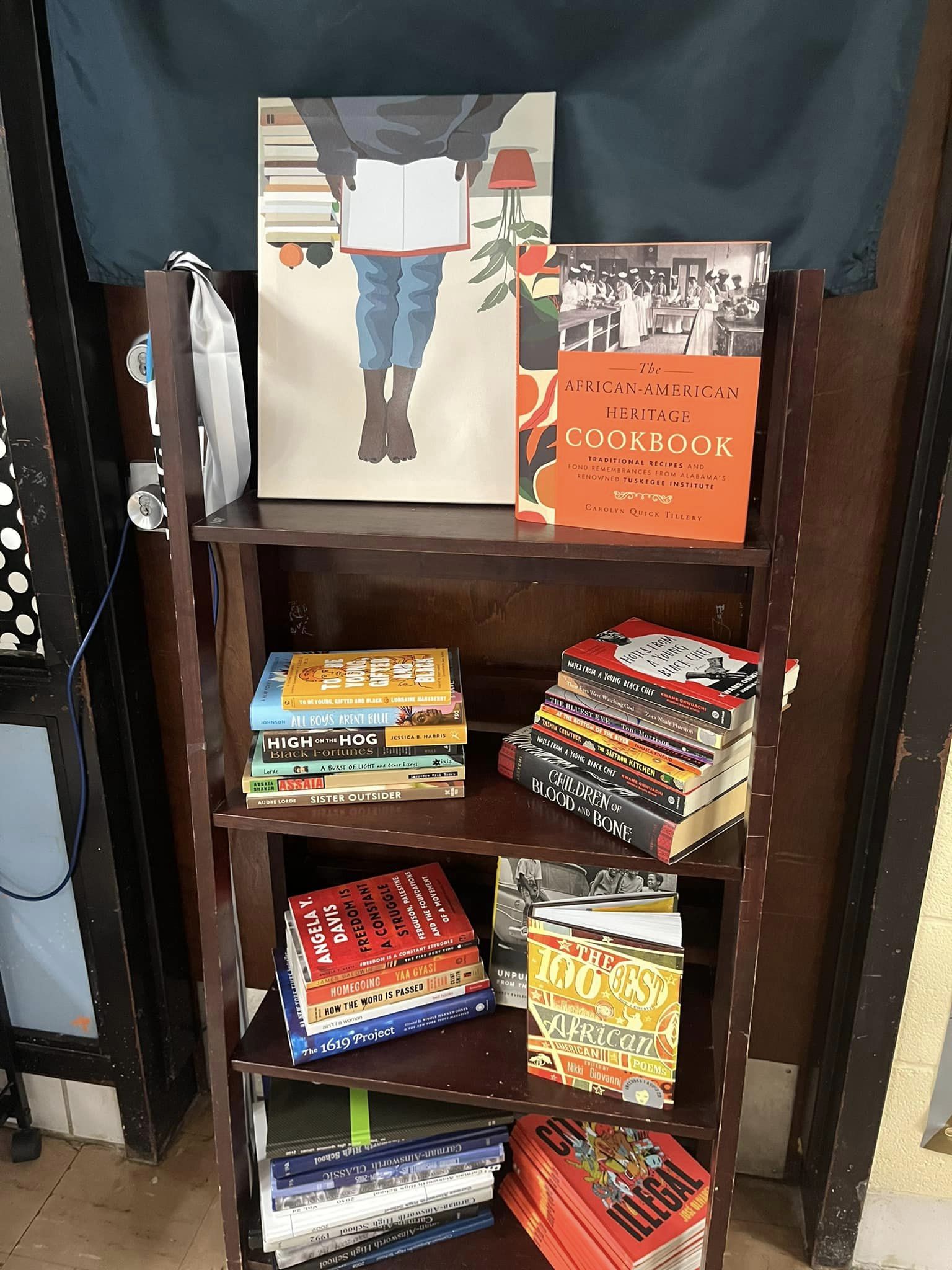

The process took a lot of work. We faced challenges, including completing requirements to bring the course to our school board and securing the right resources and training for me to teach the AP course according to the College Board’s standards.

The load was heavy at times, but the work had to be done due to the determination and passion of my students, who were powerful catalysts for change.

Finally, our efforts paid off when the school board unanimously adopted AP African American Studies at C-AHS, marking a significant milestone in our school’s commitment to offering a curriculum that reflects many of our students’ diverse experiences and histories.

The course has become a symbol of progress and inclusivity, demonstrating that student voices, when united and persistent, can indeed shape educational policies and offerings.

The evolution of student voice is not just about adding courses or changing curricula. It’s about fostering an environment where students feel heard, valued, and empowered to drive positive change.

Educators help build a foundation for a more equitable and informed future by listening to students when they advocate for their needs.

Introducing AP African American Studies is just one step toward a more inclusive and representative educational landscape—a journey on which I will always be an ally, accomplice, and supporter to my students.

Jessyca Mathews is an award-winning teacher at Carman-Ainsworth High School in Flint and the first Black woman to lead the Michigan Council of Teachers of English (MCTE). Read more about Mathews.