In This Hero’s Journey, Educators Play Inspiring Roles

By Brenda Ortega

MEA Voice Editor

Who is your audience? It’s a question every English teacher has posed, but now MEA member Rob Keast—an 18-year classroom veteran in Wyandotte—found himself answering it.

The former newspaper reporter collaborated on the memoir of Anthony Ianni, whose story is a powerful underdog tale in the vein of Rudy or Miracle on Ice. The pair’s book, published in September, appeals to many audiences, Keast said in an interview.

Sports fans of all ages. Folks in the autism community. Anyone looking for inspiration to overcome daunting obstacles and achieve big dreams.

“For a few publishers, that was a bit of a hang-up,” Keast said. “They didn’t know whether to market it as a basketball book or an autism book. And we said, ‘Well, why can’t it be both?’”

Centered: Autism, Basketball, and One Athlete’s Dreams (Red Lightning Books/Indiana University Press) is an unflinching first-person story of one boy’s experiences on the autism spectrum and his struggle for acceptance and belonging as he grew up.

It follows Ianni from a diagnosis of Pervasive Developmental Disorder at age four to becoming the first Division I college basketball player on the autism spectrum and earning a college degree.

The foreword is written by Tom Izzo, men’s basketball coach at Michigan State University where Ianni vowed as a child he would someday compete—even after doctors told his parents he would likely not play sports, attend college, or live independently after high school.

“I knew what autism was, but I had never dealt with anyone who had it,” Izzo writes. “You have those preconceived notions of, ‘He can’t do this,’ or ‘He can’t do that,’ but what I learned was that he could do anything.”

In all of those ways the book is both a captivating triumph of the human spirit and a testament to people behind the scenes who guided Ianni in his journey without a roadmap or manual for how to help him.

“We called the book Centered because that’s the position Anthony always played,” Keast said. “But the title is also a tribute to his parents and his teachers and coaches, who kept him centered and kept him moving, and showed him a way forward to all of the success he’s had.”

The book quotes from school records of special education assessments and plans, but the story is told through the eyes of Ianni who does not shrink from painful or embarrassing details.

Many educators contributed to Anthony’s achievements by treating him as an individual, not a diagnosis, Keast added. In an age when schools and teachers are sometimes made society’s scapegoats, he was happy to be part of telling a story of how educators are difference-makers,

he said.

“I can’t tell you how many scenes we worked on together in the book where I felt proud to be a teacher. So many educators in this story did our profession proud.”

The Departure

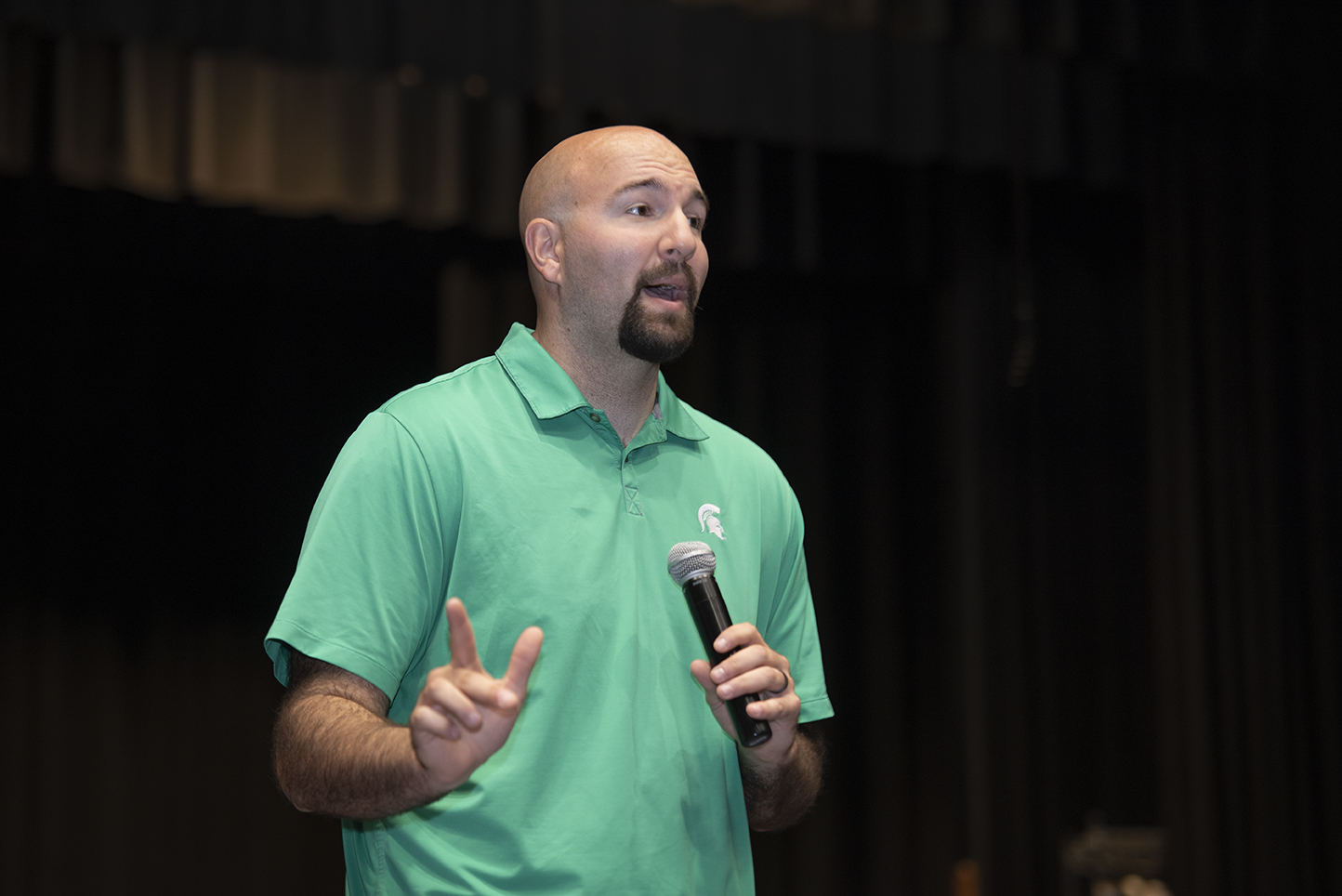

Now 32, Ianni is a married father of two and a sought-after motivational speaker with the Michigan Office of Civil Rights. His Relentless Tour takes him to schools across the country, where he shares his story one assembly at a time in the hope of replacing bullying with kindness and respect.

“If I can inspire one person at every school to make a change or be the change they wish to see in their lives, then I’ve done my job,” Ianni said in an interview, recalling his first school appearance several years ago when a bully was inspired to apologize to his victim who was a student with autism.

His first goal for writing the book was to teach people about autism. But like Keast, Ianni enjoys the fact that his story broadly appeals to anyone who relishes seeing determination win over obstacles.

“I wanted to show people that, you know what? I’ve been knocked down a bunch of times in my life, but I never quit. I never gave up. I kept getting right back up and looking toward those obstacles and looking those challenges dead in their face.”

Anthony had it especially rough as a child in part because of his size, said his mother, Jamie Ianni—an educator, coach and MEA member who retired from a 23-year career as an Okemos math and physical education teacher in 2019.

By age three, he was tall enough to ride adult rides at Cedar Point, but he could dissolve into screaming emotional meltdowns over loud noises or a change in routine, Jamie said in an interview. He could

recite lines from movies but not follow directions.

Anthony’s journey has taught her not to judge but to work hard at understanding what a child who may not be neurotypical is going through with that behavior, she added.

“A lot of times at school, they’re just trying to hold it together. They’re trying to be like everybody else, and when they come home they come unglued. Or in Anthony’s case, he’d come home, go in the den, shut the door, and sit there totally quiet because it had been so hard to keep it together for so long.”

Although few therapies existed at the time of Anthony’s diagnosis, his family was grounded by deep roots in education and sports. Grandfather Nick Ianni was a superintendent of Washtenaw Intermediate School District who fought for opportunities for special education students before Anthony was born.

His parents grew up in Michigan. Jamie played three sports at Adrian College, and Greg pitched on the MSU baseball team. They met working at Ohio University and moved to Okemos with four-year-old Anthony and older sister Allison in 1993 when Greg became an associate athletic director at MSU.

When Anthony was little, Jamie stayed home to work with him. She volunteered at his school early on and later took a part-time teaching role to “keep a finger on the pulse,” eventually becoming a respected volleyball coach, full-time teacher and advocate.

She turns accolades back at her colleagues, not only teachers but paraeducators, bus drivers, secretaries, custodians—all of the education professionals she asked to understand and help Anthony every day, many of whom are mentioned by name in the book.

“Everybody on the team is working their tails off to meet the different needs of every student in the building,” she said. “It is really an under-appreciated job. We couldn’t have gotten Anthony to the point where he is today without all of those people.”

The Initiation

One educator who appears in the book is MEA member Tom Hopper, a social studies teacher at Chippewa Middle School in Okemos, who first met Anthony while subbing in a sixth-grade physical education class 20 years ago. Hopper was supervising his group of students when he noticed one youngster who was six feet tall—towering 10 inches above his classmates—becoming upset.

Anthony could not understand why his teammates in a volleyball match didn’t hustle after the ball but instead laughed when it hit the ground. One of the expressions of Anthony’s autism was an inability to tolerate losing, and his emotions were starting to boil over.

“The difference in intensity was like Anthony was in the middle of game seven of the NBA Finals, and everyone else was playing Duck, Duck, Goose,” Hopper recalled in an interview.

He took the youngster aside. “I said something like, ‘I’m new here. Will you show me where the drinking fountain is?’ And we just went walking out of the gym, down the hall, because I knew he needed to get out of that situation just so he could process it.

“That’s when he let it all go; he was crying and saying, ‘What are they doing? Why don’t they want to win?’ And I quickly recognized this was a pretty special situation, so we just talked for a while.”

The next summer Hopper was hired for a permanent position at the school, and that fall he became Anthony’s seventh-grade teacher and eventually a close family friend.

Anthony found a home in Hopper’s classroom, which was outfitted with a couch and fun toys and trinkets. A burglar doll—complete with eye mask and 5 o’clock shadow—became the class stress ball. Squeezing it helped Anthony settle, so Hopper dropped it on his desk when the need arose.

One day, Hopper kept Anthony after class. The teacher must have heard kids teasing him about his height and obsession with MSU by calling him Jolly Green Giant, Ianni writes in the book.

The teacher said to ignore those kids. That’s what leaders do, and you’re a leader; the others just don’t know it yet. “That’s when Mr. Hopper became more than just my social studies teacher,” Ianni writes. “I saw him as my very own Mr. Feeny, from Boy Meets World; full of wisdom and warmth.

“I wasn’t convinced other students would ever follow me, but I trusted Mr. Hopper enough to believe that things would get better.”

The anecdote still draws emotion from Hopper. “He talks about what I did for him, but he has no idea how special he has been in my life and how it shaped me into a better teacher by watching him grow and learn and thrive and overcome obstacle after obstacle after obstacle. Always with the attitude and drive that ‘I’m just going to be me. I got this.’”

The same sentiment was echoed by another MEA member whose influence is detailed in the book, high school English teacher Rachel Freeman-Baldwin, known by students as Miss Free. “I can honestly say he taught me more than I ever taught him in that I made a lot of mistakes when I was his teacher.”

One mistake happened in his freshman year when she forgot to warn Anthony of a planned fire drill during class. The sudden loud noise set off his emotions, and he couldn’t calm down, yet he was kind and forgiving after. “It was a horrible experience for him, and I haven’t made that mistake since.”

She had Anthony as a student again when he was a senior. By then she noted he was less physically awkward after working hard for years to learn basketball and hone his skills on the court. He was a leader on the school’s state title-contending varsity team and had fewer issues socially.

Freeman-Baldwin then invited him to speak about autism to her freshmen, who were reading The Curious Incident of the Dog in the Night-Time, and needed help understanding the novel’s autistic narrator. She’s had him come back every year since then, except for last year during COVID.

“Every single time I cry because you hear his story, and you see how far he’s come, and you realize the experts never imagined he could be a public speaker. And he’s amazing. He does a beautiful job.”

That experience with his English teacher, coupled with an invitation four years later from then-Lieutenant Governor Brian Calley to speak at an Autism Alliance of Michigan gala, helped Ianni see public speaking as a future avenue for his life.

“When I texted Miss Freeman that I was narrating my audio book, she was so fired up,” Ianni said. “She was always the one wanting me to tell my story, saying, ‘Go on. You need to do this.’”

The Return

His path from struggles as a young child who couldn’t tolerate noise to becoming a two-time Big Ten Conference champion and member of MSU’s 2010 Final Four team has not followed a straight line.

Ianni spent two years playing basketball on a scholarship at Grand Valley State University but transferred to MSU for a chance to walk on and play for the coach he admired all his life. He would go on to win the Spartans’ 2011 Tim Bograkos Walk-On award and the 2012 Unsung Player award.

His book details career ups and downs, including an argument with MSU teammate and star Draymond Green that eventually revealed the secret of his diagnosis and sealed their friendship; and an outburst with Izzo at a time when Ianni says he felt lost—and the coach brought him back.

He will always have autism. He occasionally misreads social cues. He doesn’t understand sarcasm or abstractions without help. When his children are loud, he sometimes must step away to settle himself.

“I have coping mechanisms, but I’m going to have those struggles forever,” he said. “I’m OK with that, because that’s what makes me unique. That’s what makes me Anthony Ianni.”

He has two pieces of advice for educators working with students on the autism spectrum: keep your expectations high, and stick to the Individualized Education Plan (IEP). He feels grateful to have benefited from so many educators who went above and beyond to help him succeed.

“I don’t know how I’m ever going to thank all my teachers, because I’m a very slow learner and they did incredible things to help me adjust as a student. It showed me how incredible they are—not just as teachers, but how incredible they are as people as well.”