MI Teacher Briefs U.S. Ed Secretary on Uses of Federal Rescue Funds

Addressing students’ academic and mental health needs, while lightening the load for overstretched educators, are among the most urgent uses of federal school rescue funds prompted by the COVID-19 pandemic, according to one local union leader in west Michigan.

Addressing students’ academic and mental health needs, while lightening the load for overstretched educators, are among the most urgent uses of federal school rescue funds prompted by the COVID-19 pandemic, according to one local union leader in west Michigan.

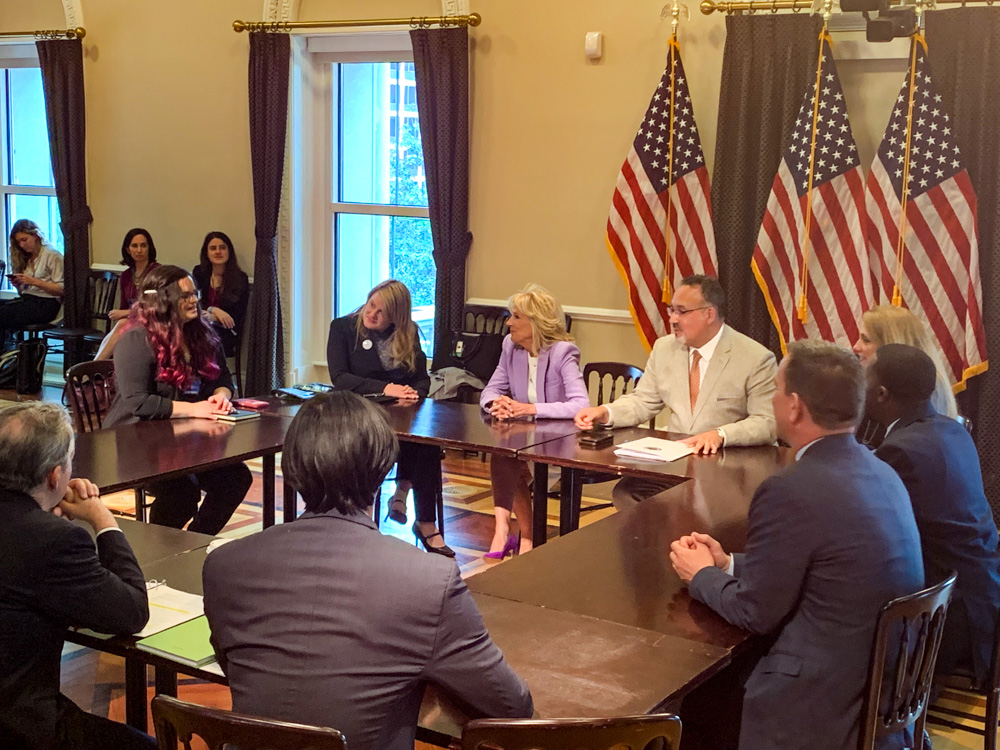

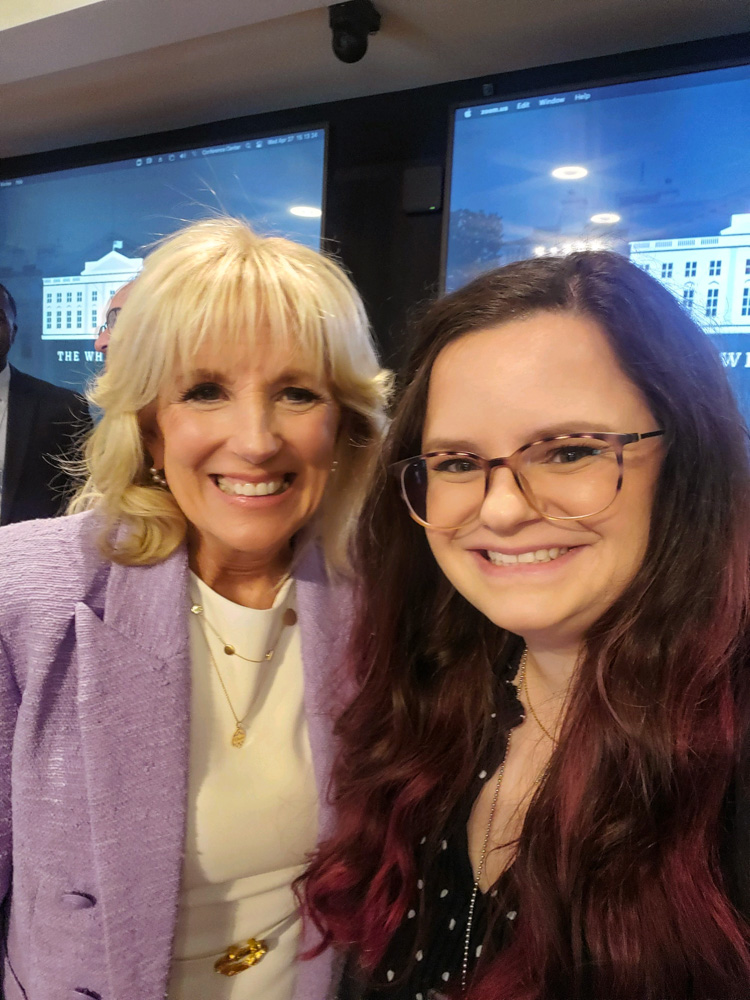

Theresann Pyrett, president of the West Ottawa Education Association, took that message to the White House on Wednesday. Pyrett is among a handful of educators from across the country who briefed U.S. Education Secretary Miguel Cardona in a private meeting in Washington, D.C.

West Ottawa Public Schools is using a portion of the $11.6 million ($1,752 per student) it’s receiving in federal aid, the bulk of which was provided by the American Rescue Plan, to add 21 new full-time behavioral and academic interventionists.

“The interventionists we’ve hired have been earth-shatteringly important for our kids,” Pyrett said.

At the meeting on Wednesday, Pyrett was joined by newly crowned National Teacher of the Year Kurt Russell – a history teacher from Ohio – plus a classroom educator from the American Federation of Teachers, and several school principals.

The group met in the Roosevelt Room to brief Cardona and presidential Senior Advisor Gene Sperling on pandemic recovery efforts. The group spoke with reporters after the meeting.

Last December, Cardona issued a seven-page letter to school officials across the country urging spending of federal rescue plan dollars on initiatives to bolster school staffing and retain educators amid a national shortage.

Federal school rescue funds prompted by the COVID-19 pandemic are providing many school districts with an opportunity to support students in ways that simply weren’t possible during decades of under-funding of public education.

For some, what began as necessary measures to address the academic and social impacts of the pandemic are quickly becoming a model for what schools can and should look like when provided with adequate resources.

West Ottawa’s new academic interventionists offer support in math and English, continually evaluating students throughout the year to identify those who would benefit from small group tutoring or placement in a different classroom setting.

The new behavioral interventionists take a proactive approach by recognizing students who may have unfulfilled emotional needs through evaluations conducted three times per year. They then work with these young people in a one-on-one setting.

This additional support not only improves the lives and academic experiences of students, but it also right-sizes workloads for existing staff who have often been playing double (or triple) duty.

“Anytime we have added support in the classroom, it changes the way we do our job,” Pyrett said. “More hands to lift up our students makes for a lighter load.”

Many other schools across Michigan are also using school rescue funds to simultaneously address the mental health needs of students while bolstering staff numbers. Utica recently doubled the number of school social workers in the district using federal aid.

In a diverse district where more than half of kids are economically disadvantaged and many students are English language learners, West Ottawa is providing a range of benefits and resources through federal school rescue funds.

The district has expanded summer school programs and provided better technology in classrooms, including document cameras for educators and a 1-1 student to Chromebook ratio from Elementary through High School.

Staff created the “Panther Closet,” a place where students can readily and discreetly access everyday necessities like food and laundry supplies. During periods of remote learning, school buses installed with hotspots were driven into areas with lower rates of broadband access.

While students continue to struggle with the effects of major upheaval over the past two years, benchmark testing and other measures from classroom educators show West Ottawa students are learning and growing – thanks to ongoing work to deliver necessary supports.

“All of the money was spent with students in mind,” Pyrett said. “When we’re seeing students with higher socio-economic needs achieving academic growth during a global pandemic, we know we’re spending the money right.”

Students weren’t the only ones who benefited from increased funding. Staff morale improved when they finally received long-sought academic and behavioral support for their students. Many also appreciated financial rewards for staying in the job through tough times.

West Ottawa staff received a series of bonuses to align with the extra work required to educate students during a pandemic. The model has been used in many districts, most notably Flint Public Schools, which is using 3.5% of $155.3 million it’s receiving to recruit and retain educators during a historic shortage.

Many West Ottawa educators are also electing to teach in the expanded summer school program, where they are paid $250/day with a $1,000 bonus for completing the 8-week program.

Statewide only 13.7% of federal rescue funds have been spent so far, providing ample opportunity for other school districts to craft plans that take into account historically high needs among educators and students alike with successes achieved in other communities.

West Ottawa educators have coined a new term for their successes, “COVID Keeps,” which is a list of programs and initiatives begun during the pandemic that were so effective the school district is exploring ways to continue them indefinitely.

Pyrett is part of a group evaluating what was learned during the COVID-19 pandemic and exploring options to continue programs that remove barriers to a quality education for her students.

But Pyrett knows increased state education funding is key to continue those crucial programs when these school rescue funds expire in 2024. She is both hopeful and anxious about the future.

“If increased funding levels were to continue, it would mean that our students have fair and equal access to a high-quality public education,” Pyrett said. “But now that we’ve been funded in the way that we should be funded, how do we peel back these supports if we have to go back? How do I tell my students that these programs that have helped them succeed are no longer available?”