Blind teacher and Paralympic athlete shows students anything is possible

MEA member John Kusku has faced extra challenges throughout his 39 years, but he learned a key philosophy from his mother who told him as a little boy: Goals might be harder for you to achieve, but you can still do anything you want. “That’s been kind of the mentality of my life,” Kusku says.

The belief has served him well. Legally blind, Kusku is a two-time Paralympian for Team USA in addition to teaching math and physics at the Oakland County Technical Campus Southwest, where his example shows students anything is possible with commitment and hard work.

“The kind of thing I want my students to see is that people with disabilities, including maybe themselves, can be very highly successful,” said Kusku, whose wife Jessica is an MEA member teacher of visually impaired students in Livonia. The couple has a 10-year-old son.

Kusku has a rare genetic condition that causes progressive vision loss. He was born with 10 or 15 degrees of vision, which has since narrowed to less than one degree, “whereas someone with normal sight would have around 180 or 210 degrees of vision,” he said.

He and his family learned of it when he was just five years old. “The doctor was very clear in saying I could live a normal life but I would never drive a car. He predicted that I would be totally blind by the time I was 18, and my mom just said, ‘OK, those are the restrictions we have.’”

Growing up in Warren, Kusku loved playing in a youth soccer league, but when he got to middle school age – his eyesight worsening – players were getting bigger and stronger and the game was faster. “It stopped being fun,” he said.

“I didn’t know it at the time, but I was becoming a little depressed because I didn’t have anything to do. The thing that I really enjoyed, team sports, was kind of gone. And that’s when I came across goalball.”

Kusku was attending a sports education camp for blind kids at Western Michigan University, run by the Michigan Blind Athletic Association, where he got to play a very competitive level of the sport designed exclusively for visually impaired athletes.

“Goalball is played on a court, three against three, where the players are directly in front of each other,” Kusku explained. “I got put down the line from this guy who threw the ball so hard it hit me in the nose, and I got the first and only bloody nose of my entire life – and that was when I was hooked! I was like, ‘Oh dude, this game’s awesome,’ and that moment became a huge changing point.”

Soon Kusku was invited to be part of the Michigan team traveling to youth national championships, and he formed a Michigan club travel team that played all over the U.S. and Canada. The experience proved to be beneficial for him socially as well as athletically, he said.

At the time he was a young high schooler, attending school and receiving services from a Teacher Consultant for the Visually Impaired (TCVI) who taught him to read braille and use adaptive technology. A separate mobility specialist showed him how to use a cane and navigate bus systems.

“I needed to use my cane in certain settings, but I wouldn’t because I didn’t want the embarrassment of it,” Kusku said.

Taking road trips with other athletes – some college students – changed his attitude, he said.

“We would roll out of a 15-passenger van at a rest stop, and there’d be like 12 of us and 10 of us using canes, and it was OK. It was OK to tell the person behind the counter, ‘Hey, I can’t read the menu; can you tell me what you have?’ It was the first time I had been in those sorts of social settings.”

Today Kusku brings those experiences to young people as the coach of a youth travel team: “paying it forward, so it’s pretty cool,” he said.

Goalball is played on a 30×60 volleyball-size court with players wearing blackout goggles for fairness as they try to get a rubber ball into a four-foot-tall net running the entire 30-foot width. Players never cross half-court, and rules govern where the ball must hit the floor before crossing over.

The thick rubber ball is not inflated but has holes in it with two sleigh bells inside, so it makes noise while moving. To defend their goal, players crouch and attack the incoming ball – “kind of the opposite of dodgeball,” he said. “I want to get hit because otherwise it scores.”

In 2009 Kusku made Team USA in goalball for the first time, but the team did not qualify for the 2012 Paralympics, in which the world’s top disabled athletes compete in the same years as Olympic Games.

Kusku and the American men’s team won silver in the 2016 Paralympics in Brazil and competed again in Tokyo in 2020, coming in fourth. This year he narrowly missed the cut despite remaining among the top players in the U.S.

He plans to continue training for 2028. Meanwhile, he’s taken up cross country skiing and is pushing to become an elite competitor in that challenging sport. The first time he ever skied was in December 2022, and since then Kusku has raced in several competitions across the country.

Blind skiers have a guide who wears a microphone headset with a small speaker on their back to create sound and descriptions of terrain for orientation. At first Kusku thought he might try to compete in the 2026 Winter Paralympics, but he’s revised that goal date to 2030 with the difficulty level in mind.

“People say that cross country skiing is possibly the hardest thing to do on earth other than maybe hitting a baseball,” he said. “You’re literally balancing on one foot 90% of the time.”

He was inspired to become an educator by his 11th-grade Algebra teacher’s passion and excitement. He hopes to be a similar inspiration to his Career and Technical Education students, for whom he embeds math lessons into the welding work or health care roles they’re learning.

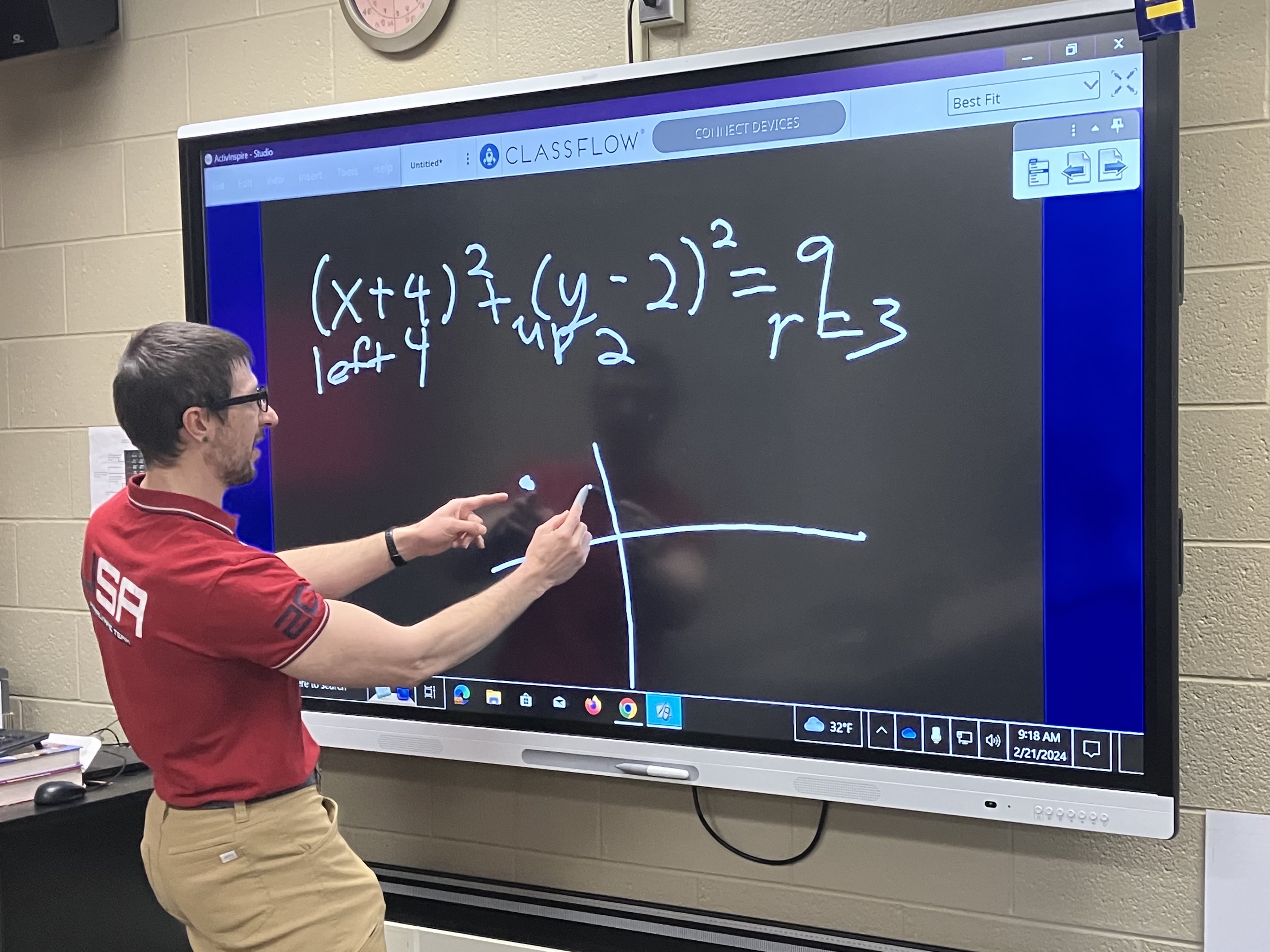

Kusku teaches with a smart screen that reads what is on the board, and he keeps notes about students to help him connect names with people. Like any educator, his biggest goal is to create relationships which clear the way to learning, and then students don’t think much about his blindness, he said.

“Because I function as well as I can, they really don’t understand how little I can see until pretty far into the school year. I don’t shove it in their faces, but my hope is they’ll realize like, Oh! He really can’t see, and he still can be a normal human being. Beyond that, he can also be an elite athlete.”