Delta professor seeks change through history

MEA member Amy French disrupts students’ expectations in the history classes she leads at Delta College in Bay County’s University Center by asking at the outset: “So what am I teaching this semester?”

French isn’t joking or trying to catch anyone napping with her day-one question. As head of Delta’s history department, French is acknowledging the historical narrative has revolved around wealthy white men and signaling she wants to know what students want to learn.

“The working class feels disenfranchised from history. People of color feel disenfranchised. People of non-dominant religions feel disenfranchised. So I will start teaching from whatever they say: Can I learn more about the LGBTQ+ community? I’m working class; can I learn more about my people? What about women?”

As its coordinator, French led a curricular change in the history department at Delta to highlight marginalized voices in all classes, “so students will find themselves in every single history course because it is the story of all of us,” she said.

A former stockbroker who followed her passion toward uncovering and bringing forth lesser known stories of excluded and disenfranchised people, French received the Maurine Wyatt Feminist and Gender Equity Award in a ceremony at the MEA Winter Conference in March.

Her work at the college spans multiple large-scale projects beyond her classroom and departmental leadership duties – a fact she hadn’t much thought about until seeing it all compiled for the award.

“I don’t have a master narrative in my life. I’m not thinking I’m going to do this thing, which will lead to that thing, and then I’m going to have this planned outcome. Everything ties together because I see that here’s a hole I can fill, there’s another gap that needs bridging. One thing leads to another.”

Soon after accepting a full-time tenure-track position at Delta in 2010, French and her history colleague and partner-in-creativity Laura Dull – who nominated her for the award – launched the Humanities Learning Center (HLC) to demonstrate the importance of the arts and humanities.

The HLC brings in speakers for an open-to-the-community series of brown bag talks throughout the year – informal sharing of powerful stories and ideas in a public square which French compares to Plato or Aristotle standing on the Acropolis to speak in ancient Greek times.

After handing off leadership of the HLC, French filled another hole: Not every History or Heritage month was equally represented on campus. While Black History Month might get recognized, Native American History Month or Asian and Pacific Islander Heritage Month might not, for example.

Over the past few years, she created “Celebrating Our Stories,” a learning repository for each history or heritage month which she promotes along with HLC and other related events. She now brings students’ work into the project with an honors option in which they identify missing narratives and complete the research and writing for inclusion in the collection.

“I love seeing it through their eyes and what they choose to focus on,” she said. “It constantly teaches me and refocuses me, and that’s the true joy. We’re all lifelong learners, and students inspire us to be better versions of ourselves.”

As chair and co-chair of the Women’s History Month committee for more than a decade, French has delivered dozens of talks on women’s struggles for equality, her personal focus and area of expertise.

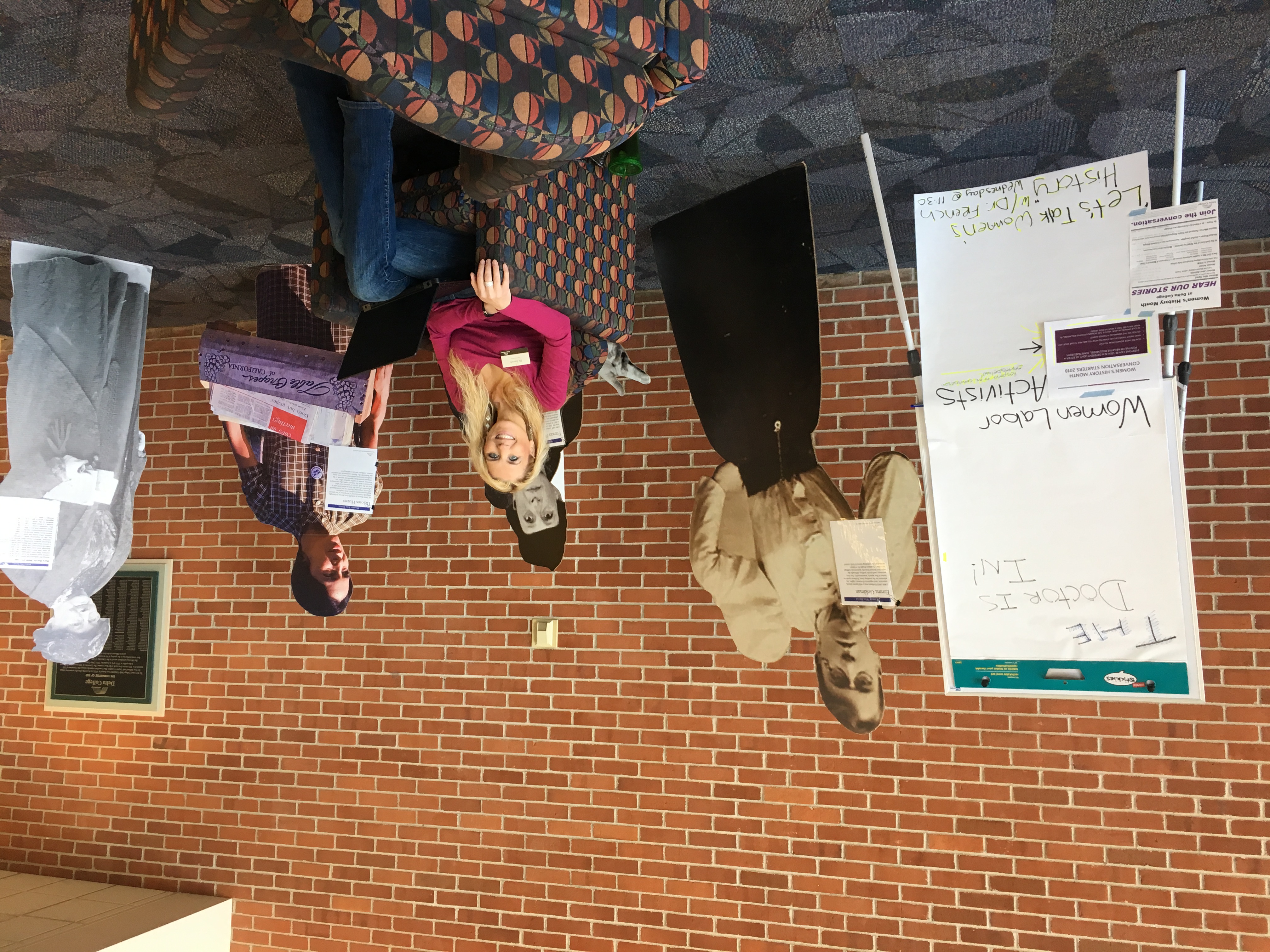

An early passion project French again initiated with Dull – dating back to when she was an adjunct working on a PhD – was an online women’s history exhibit called Women who Dared. The pair later linked cardboard cutouts with information and QR codes around campus for Women’s History Month.

And French further built upon Women who Dared after the disappointment of the 2016 presidential election when a colleague’s young daughter was shoved and taunted by a boy who said, “See? I told you girls can’t be president.”

“It broke my heart,” she said. “I thought, we can do better than this. I firmly believe that you can’t be what you can’t see, so that’s when I created See a Girl, See a Leader.”

French made t-shirts with the project’s name and wrote scripts about women leaders through millennia, which she invited local schoolgirls from across the Saginaw Bay region to record for airing on a local radio station and to be housed online with Women who Dared.

“It was so wonderful to hear little girls reading these stories and their voices being broadcast. I contacted the teacher of the boy who pushed my friend’s daughter, and I asked, ‘Could you play this in the classroom when it airs during NPR’s Morning Edition?’”

Dull – the colleague and frequent project partner who nominated her for the MEA award – said French was asked by Delta College President Michael Gavin why she puts in so much extra work on projects. She answered, “because it is important.”

“She spends the hours celebrating the stories of women and other marginalized voices because they are important and it is important work,” Dull wrote in her nomination. “That is a hallmark of true service.”

French grew up in Saginaw and attended Delta as a first-generation college student before earning a degree in history and communication at University of Michigan. She enjoyed a first career as a stockbroker but found her calling pursuing a master’s degree at Central and a PhD at Wayne State.

She holds a doctorate in legal history with an emphasis on labor law and has spoken across the country on an article she wrote in the Michigan Historical Review and later adapted for the Michigan Judiciary’s Journal, The Court Legacy: “Mixing It Up: Michigan Barmaids Fight for Civil Rights.”

In 1945 Michigan passed a law saying women couldn’t be bartenders in cities over 50,000 population unless their husband or father owned the establishment. In Goesaert v. Cleary, the Supreme Court upheld the law, ruling women are dependent and not guaranteed a right to wage work.

That decision referenced a 1908 ruling in Muller v. Oregon, which said women’s procreative value is more important than their right to labor on their own terms – and both of those rulings are still used to justify the court’s decisions today in abortion rights cases, for example, French said.

“That’s part of why my work on Goesaert is important is that it ties together over a century of sexual discrimination against women in the workplace and it uncovers why women have been treated as secondary citizens in work.”

Her philosophy aligns with Sister Ardeth Platte, a pacifist nun with ties to Saginaw imprisoned for anti-nuclear protests and who became the basis of a character on the TV show Orange is the New Black. French interviewed Platte for a history of the founding mothers of Saginaw’s domestic violence shelter.

“I just remember being awestruck at the time and asking ‘How did you do all this?’ And she said, ‘Think globally, act personally,’ so I try to keep that with me and remember how ordinary actions can become extraordinary.”

She is proud to work at Delta College, where her own journey began, because it provides the kind of small class sizes and caring instructional environment that helps students learn, grow and thrive.

“The students inspire me,” French said. “My only regret in teaching at a two-year college is that I only have them for two years. But I’m their mentor for life.”