Clawson teachers light the way: contract settles all newly restored topics

By Brenda Ortega

MEA Voice Editor

In her nearly 14 years as president of the Clawson Education Association, Kelly Pearson has not bargained a better contract than the one she recently signed. Overwhelmingly approved by membership, the deal struck different responses between early-career and longer-term educators.

“Overall, people were happy,” Pearson said of reactions during a meeting to review the tentative agreement. “But for those veterans who remember what it was like before, all of a sudden they’re like, ‘It’s back the way it used to be.’ Whereas the newer people are saying, ‘This is a whole new world.’”

It wasn’t primarily the deal’s strong financial aspects which drew sustained applause at the end of the 90-minute review session, she said: “I was watching smiles break out in the room as (MEA Executive Director Chris Pratt) went over it. People are excited about what we got back in the restored topics.”

With a contract expiring at the end of last December, the Clawson unit was among the first in the state to begin negotiating over important topics that had been barred from tables for a dozen years or more by politicians who sought to weaken unions’ collective bargaining strength.

Last year a new Legislature joined with Gov. Gretchen Whitmer to restore the rights of educators, whose voices had been silenced around several subjects they had previously bargained for decades – relating to evaluation, placement, layoff and recall, and discipline and discharge.

Other changes passed last year eliminated one-sided penalties against educators when contracts expired without a successor agreement in place – thereby balancing what had been unequal power granted to school districts – and returned the ability of locals to choose payroll deduction for union dues.

All of those new laws go into effect on Feb. 13.

“Honestly what the state Legislature did was amazing,” said Pearson, a first-grade teacher and 25-year classroom veteran. “Take just one example: evaluation. There wasn’t much that we really had to do to get the changes we needed, because the law is so great.”

Championed by former MEA-member educators in the House and Senate who now chair Education Committees in their respective chambers — Sen. Dayna Polehanki (D-Livonia) and Rep. Matt Koleszar (D-Plymouth) — the new evaluation law removes state standardized test scores from teacher ratings beginning next school year.

Educators had doggedly advocated over several years for fixes to problems of fairness and accuracy in the teacher evaluation system overhauled by Republican lawmakers and Gov. Rick Snyder in 2011.

Part of larger efforts to make it easier to fire teachers, the evaluation system designed in 2011 discouraged collaboration, downgraded those working with the neediest students, ratcheted up the importance of standardized test scores, and sought to penalize rather than develop educators.

“It was a bad system, and I’m so glad the Legislature was able to do what they did,” Pearson said.

Among other evaluation changes passed last year, student growth lowers from 40 to 20% of an educator’s score, meaningful measurements of student performance are determined locally, a process returns for challenging unfair ratings, and educators deemed effective can move to triennial evaluations.

While keeping state-approved evaluation tools required since 2015, such as the Charlotte Danielson Framework and 5 Dimensions of Teaching and Learning, the new law allows bargainers to adapt the tools to meet local needs.

Such an editing of the 5-D+ tool used in Clawson will happen through a committee forming as part of the contract settlement. Made up of equal numbers from administration and teaching ranks, the committee will look at potential modifications to make the tool more appropriate and less cumbersome.

“Maybe we look at the requirement to post learning targets on the board every day and decide to pull that out as an indicator that doesn’t need to be there for good teaching to happen one way or the other,” Pearson said.

“Or with my first graders – requiring they demonstrate deeper-level questioning. I’m teaching them the difference between a question and a statement, and some kids still struggle. Those are the types of things the committee will discuss, but the point is teachers will have a say in deciding what makes sense.”

The goal is to have the work done on the tool by spring and bring recommendations back to the bargaining team for approval.

Key to settling the large number of open issues in the contract, including salary and benefits in addition to the newly restored topics, was the negotiation method used to bring the two sides together, according to Chris Pratt, the MEA staffer who assisted the Clawson team.

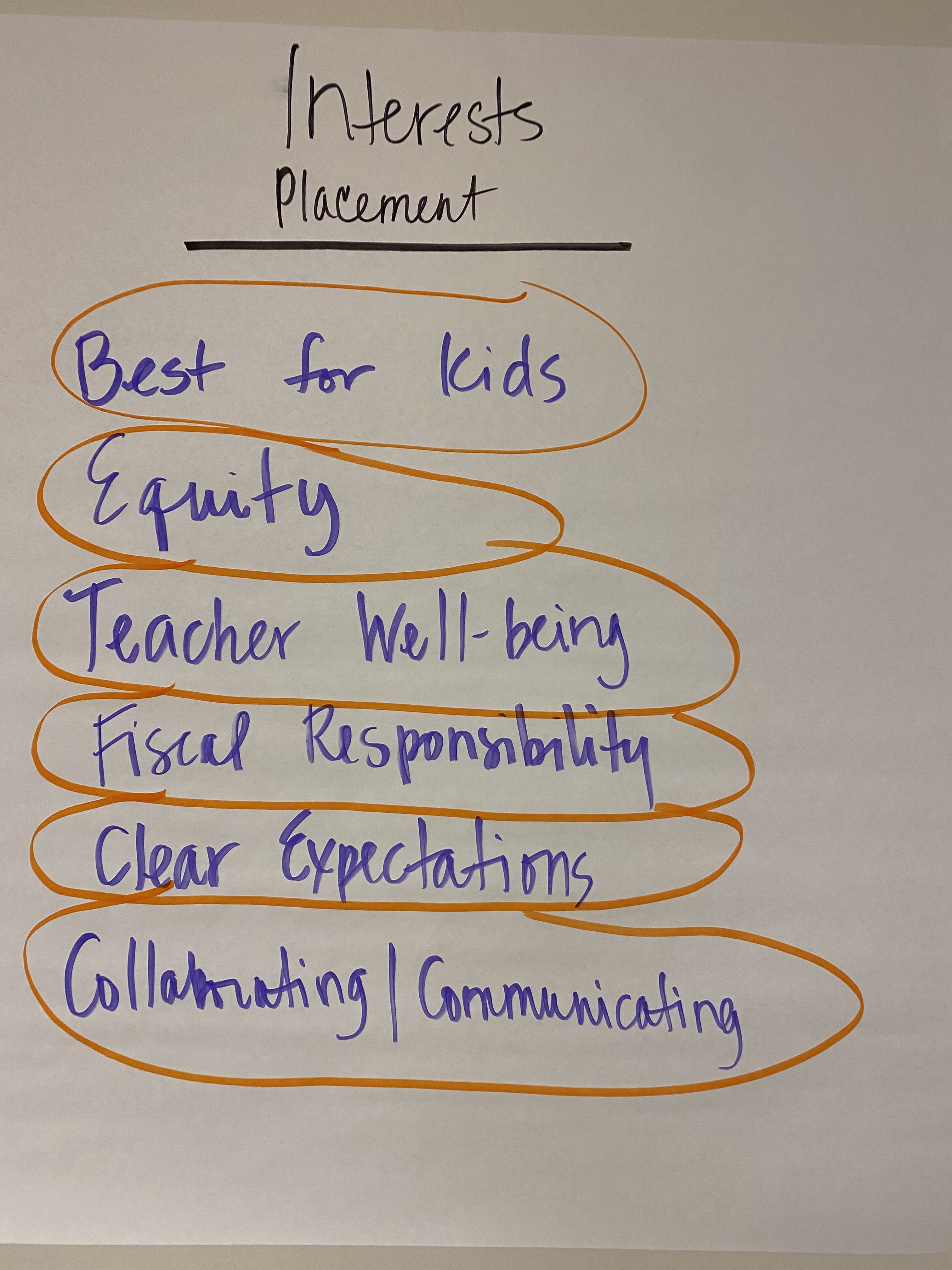

Both sides agreed to undertake Interest-Based Bargaining (IBB), a model that encourages collaboration through a formal process for advancing facts and perspectives, listening, developing shared interests, and brainstorming to seek common ground, Pratt said.

“I first used IBB a year and a half ago, and it was not my first choice, but now I’m a believer,” Pratt said. “It’s beneficial to build a culture where administrators and teachers listen to each other. They may not agree, but to listen and understand where the other party is coming from really does help.”

The union president agreed IBB was key to success — though not easy or fast; the bargain took 88 hours — and she added the impetus to try it came from second-year Superintendent Billy Shellenbarger. “It’s his style to work collaboratively,” Pearson said.

“In IBB, instead of the traditional approach where you pass proposals back and forth across the table, you work together collectively as a team. We even mixed up where we sat.”

Bargainers completed a two-day training to build trust and learn the process, led by MEA Executive Director Grat Dalton. Determining shared values and listening to each other on each topic helped the group work through dozens of ideas — amid real struggles — to find agreement on all restored subjects.

“It was interesting to be a part of it,” Pratt said. “You saw teachers having meaningful conversation over these very important subjects for the first time in over a decade, and the result is a small bargaining unit of about 100 teachers figured it out and will hopefully end up being a lighthouse district.”

However, not every district has a leader interested in working collaboratively, which makes it important for local unions to organize and build solidarity so they can present a strong message and unified front at the table, said Craig Culver, MEA’s Statewide Bargaining Consultant.

“Teachers were once singled out from other employee groups to have their employment rights removed by law, but they no longer have to be second-class citizens,” Culver said. “Next comes the need for an organized membership to help support what will be an extra heavy lift in districts resistant to restoring basic workplace rights for teachers.”

Pearson recognized the significance of the bills to return teachers their collective bargaining rights as the measures were being debated in the Legislature. She was among several leaders from MEA locals who spoke before the House Labor Committee last spring.

In her testimony, Pearson told of a teacher in her unit whose job assignment changed involuntarily nine times in eight years — once shifting her from middle school to developmental kindergarten — a practice unfair to both educators and students but which the union was not allowed to address.

With those bills signed into law, the Clawson bargainers established staff placement rules which retain administrators’ flexibility to assign people where needed but also limit involuntary placements of tenured teachers to once every five years.

“We got back almost all of the language we had before they took away our right to bargain placement, so what happened to that poor teacher — moving nine times in eight years — couldn’t happen now,” Pearson said. “As it should be.”

Despite bumps in the road, the deal forged in Clawson also re-established “just cause” as the rightful standard for disciplining a teacher instead of the extremely low bar of “not arbitary and capricious,” which has empowered school districts to more aggressively target and discipline or discharge teachers.

As importantly, the contract spells out procedures for progressive discipline so everyone – administrators and staff alike – understands the steps and progression of repeated discipline; problem areas are communicated; and coaching gives individuals opportunity to improve.

“Progressive discipline didn’t exist in our contract even before it was taken away, so now we have that,” Pearson said.

In addition, the bargainers met in the middle on layoff and recall rules, she said. Once based solely on seniority, the pendulum had swung far the other way to allow a fraction of one point on a teacher’s evaluation score to mean a 20-year veteran was laid off over a less experienced, less expensive teacher.

The new layoff and recall policy in Clawson will look first at each teacher’s evaluation rating instead of individual number scores — effective, developing or needing support — and if those are equal, then seniority will be used next.

The deal also restores payroll deduction for union dues next fall, which simplifies and splits the amount over two pay periods. “We got everything,” Pearson said, adding the union conceded on two disagreements over evaluation: keeping the 5-D+ tool and adding a small deduction for attendance.

The team saved financial discussion for last but certainly not least, she added. The final deal continues an effort begun in the previous contract to beef up the salary schedule and restore steps for those who were frozen and took a pay cut during hard times.

Everyone will see at least a 3% increase on base salary, significantly higher longevity bonuses now beginning at five years, added days for bereavement, class size reductions, and more.

When agreement couldn’t be reached on raises or steps in the third year, the union agreed only to a two-year contract. That choice was made possible by repeal of a union-busting rule passed in 2011 which penalized only one side financially — educators — when negotiations reached an impasse.

“Now if we don’t have a settled contract come December 31st, 2025, everyone on steps will move up one at least,” Pearson said. “That wasn’t the case for a while.”

The longtime leader gave kudos to the CEA bargaining team, comprised of a balanced group of veteran, mid-career and newer educators — including a probationary teacher in her first negotiation — for working together to benefit all, including students and the community.

She also credited MEA’s Pratt and Dalton for their expertise and preparation, and she thanked the Legislature for delivering needed change. Next, she looks forward to training her leadership replacement and teaching for several more years.

Coming from a family of educators — including her parents and brother — Pearson said, “I’m happy my last contract as president was the best one. With everything we’ve been able to get back, I feel like we’ll be able to recruit the next generation of young people. We’re rounding the corner.”

The successful outcome in Clawson doesn’t mean the work is easy or done, but it reveals what’s possible, added MEA’s Pratt.

“It’s a heavy lift to get this language back into contracts,” he said. “It’s not like you snap your fingers and suddenly it’s back to where it was — it will be busy and tough. But when all is said and done, I do believe this is going to be a really big year.”