Get ready—AI is transformative: ‘We have to focus on the speed of change’

By Brenda Ortega

MEA Voice Editor

Artificial Intelligence (AI) is unlike any technological tool that has come along in the history of higher education, and educators and institutions must immediately begin the ongoing work of adopting it and adapting to the rapid change it will bring.

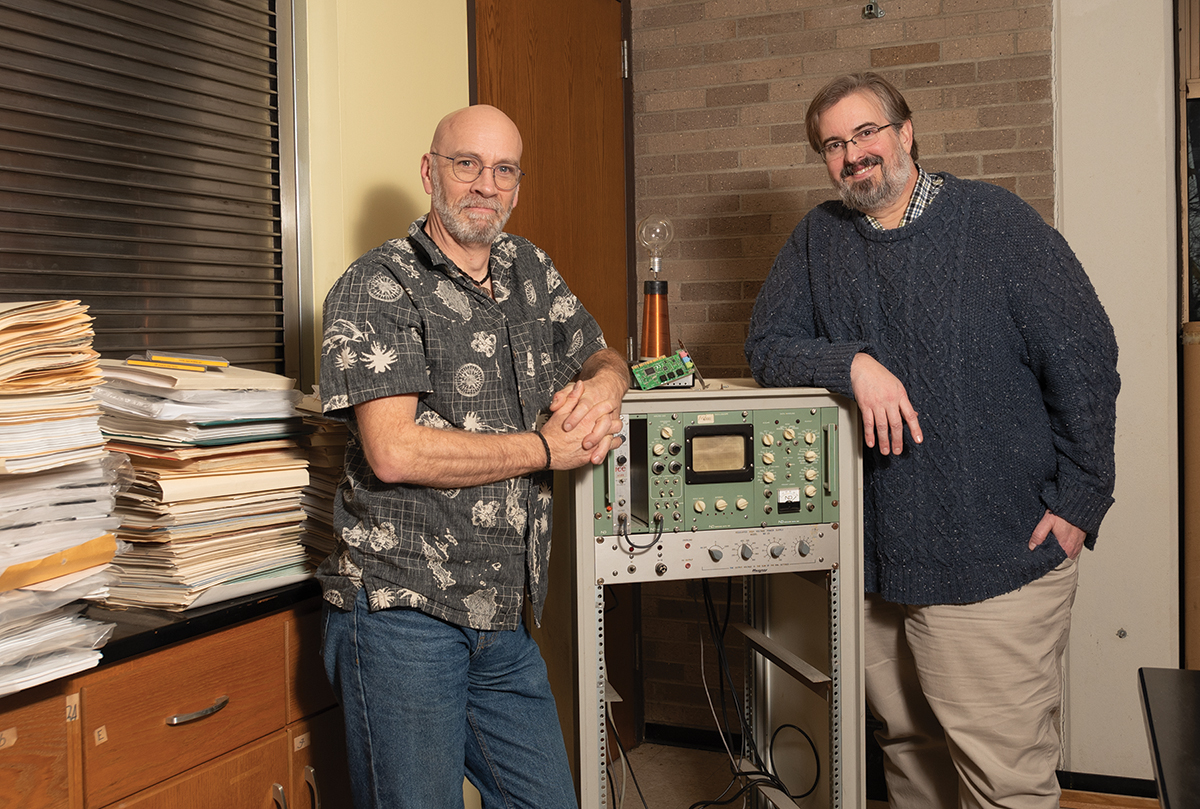

That was the striking thesis laid out in the opening sentences of a presentation delivered by MEA members Steve Tuckey and Mark Ott – two professors from Jackson College – at an MEA conference themed around the hot topic of AI in higher education.

“We keep hearing references of ‘AI is like a calculator,’ or ‘It’s just like when the internet came along,’ Tuckey said at the fall conference held by MEA’s Michigan Association for Higher Education (MAHE).

The pair delivered their urgent message at the MAHE conference with humor and historical context.

“AI is similar to those technologies in many ways – but it is also very, very different. We have to focus on the speed of change and why acknowledging it is a must. We can’t stick our heads in the sand or dismiss it as a passing fancy with ‘Oh yeah – it’s like the Segway we’re all driving around town!’”

AI has been around for decades, but the November 2022 release of ChatGPT captured imagination with its ability to instantly analyze information and generate sophisticated text responses to prompts. The large language model mimics human intelligence with its capacity to learn, solve problems and converse with the user.

An open-source platform developed by OpenAI, a research and development company in San Francisco, ChatGPT set a growth record by attracting 100 million users in just two months – a milestone that took four years for Facebook to achieve and more than two years for Instagram.

Educators quickly began using the ChatGPT technology and other models arising in its wake to semi-automate time-consuming tasks: generating ideas or drafts for emails, lesson plans and differentiation; assessments; assignment instructions or feedback; and more.

Concerns have also arisen. Will students read, write, think and learn if a machine can do it for them? Can we protect privacy? Is it possible to root out conscious or unconscious biases built into systems by the humans who devised them? How do we address it when AI’s power is harnessed for ill intents?

Then there is the question Mathematics and Physics Professor Tuckey and Chemistry Professor Ott turned into the tongue-in-cheek title of their presentation. The Race is On: Will I be able to retire before AI makes my job obsolete?

The two were not sharing practical uses nor debating if machines will take over life as we know it in a science-fiction-come-true scenario. “If that does come, we’re out of a job anyway because we’ll be surviving in the hellscape that is AI singularity, and that is a different talk,” Tuckey quipped.

Instead, they pointed out technology has always disrupted cultures, changed the way societies function, and in turn been changed by users in a recursive cycle. The written word not only altered how humans process and recall information but itself evolved from stone tablets to the printing press and internet.

“Socrates used to complain at great length about how people are writing now and not remembering things like they used to, and that’s cheating!” Tuckey said. “So this idea that technology changes us and we change technology has been around for a long time.”

The difference today is in the pace of the evolution, Ott said. The internet took years to develop because it required infrastructure. Cell phones are ubiquitous, but their use grew over time from 2008. “Whereas these chatbots are amazingly easy to interact with, making the barrier for entry really low,” Ott said.

Users can already design their own chatbots, no coding required, he added: “I read just this morning about a professor of physics who’s designed three AIs, and one of them is a conversation AI trained on his syllabus with the sole purpose of answering students’ questions.”

Perhaps most mind-blowing to Tuckey is the fact that large language models are able to understand the real world without having a concept of physical reality and can learn recursively from both external texts and those created by AI – “so it gets really good, really fast.”

“There was a time when the word ‘computer’ referred to a human being,” Tuckey said. “We would never say that now. In 50 years, will there be a need for engineers when you can just say to the machine, ‘Here’s the problem; give me five different solutions’?”

Ott shared a recent example to underscore the point. At Northwestern University researchers developed an AI algorithm on a laptop that was able to respond to the simple prompt: Design a robot that can walk. The machine accomplished the task in nine attempts over 26 seconds.

The resulting robot which was 3-D printed from a blueprint, looking like no creature that has walked the earth, was powered by air. The researchers called it “instant evolution,” recognizing it used to take weeks of trial and error for a supercomputer to evolve a robot over multiple attempts.

“From prompt to nine iterations in 26 seconds, and it worked,” Ott stressed.

Tuckey referred to it as “artificial selection” – as opposed to natural selection – and restated the duo’s central thesis: change is happening quickly; it will shift reality in the near future of the world which our students are preparing to lead and inhabit; and educators must keep up, stay open, try new things.

“One way that I think about this is I’m helping my students become prompt engineers,” Tuckey said. “How do they communicate with that machine to get information, to process it, to connect it? For me, higher ed has become less about how do we get answers and more about how do we figure out better questions to ask?”

He urged peers to “think deeply about what professional development looks like at your institutions,” adding he is chair of the Faculty Professional Development Committee at Jackson College. “The problem we run into is that staying current becomes part of our full-time jobs, and how do we negotiate that?

“Literally – how do we negotiate that into our contracts? Professional development is a big deal. How supported are you to do meaningful, ongoing professional development? Throwing you a couple hundred bucks every year to attend a conference or get a journal isn’t good enough anymore.”

Ott encouraged educators concerned about remaining relevant to consider whether to pursue upskilling, which is building on existing skill sets, or reskilling to pivot in a different direction (teaching climate science instead of chemistry), or to shift away with training or certification in a new field of study.

Thoughtful adaptation is key, Tuckey said, referencing the ideas of evolutionary biologist Charles Darwin from On the Origin of Species.

“It’s not the strongest of the species that survives, nor the most intelligent, but the one most responsive to change. Responsive to change doesn’t mean you automatically get better – it’s that you recognize change and you respond to it, and the way you choose to respond is key.”

RELATED STORIES

CMU prof: ‘We can do this. We have to.’

Veteran: AI ‘democratizes education’

SVSU profs: AI can boost creativity