MEA Book Studies Tackle Timely Yet Difficult Topics: Racism, Diversity, Equity, Inclusion

By Brenda Ortega

MEA Voice Editor

When Dawn Weaver facilitates trainings or discussions around race, she talks with educators about the importance of creating “windows and mirrors” in their classroom practice.

“I’ve always tried to have representation—not just for African-American students but any marginalized individuals—and make sure that everybody in my class is seeing themselves and seeing others,” the MEA member said.

Despite the stresses of being an educator in a pandemic, this fall the veteran upper elementary teacher in Romulus Public Schools took on the added role of co-leading two virtual MEA book studies for members through the Center for Leadership & Learning.

Through two books studied in separate five-week sessions, participants explored systemic racism and ways to become more actively involved in dismantling systems of oppression: White Fragility by Robin DiAngelo and How to be an Antiracist by Ibram X. Kendi.

“Even when I come home so exhausted from working and everything, I am recharged doing these book studies,” she said. “It’s very energizing that this work is being done and that people are eager to do this work.”

They were so eager, in fact, that in the last session folks were asking if the study could extend into one more meeting. “They were saying, ‘I don’t know when I’m going to talk with you again about this,” she said.

The SCECH-eligible teleconference sessions were not done lecture-style. “We were sharing and having discussions. The majority of it is in this magic of the breakout rooms. I get way too excited about breakout rooms, because that’s where you are able to have the most impact.”

Weaver uses supplemental videos, articles, and materials to break down the books’ messages for easier understanding and to show how to bring antiracist action to life in classrooms of all ages.

For example, to prepare participants to talk about sensitive subjects, Weaver discusses the concept of socialization through a short video describing “the ladder of imprint.” The lesson reveals that it is not negative or a critique to say someone holds “biases.” It’s just fact.

“When we use that word, people want to say, ‘Nope. I don’t have biases.’ But the truth is we’re all socialized; we all have biases. The goal is becoming more aware of those biases and thinking about how does my bias work within the systems, policies and procedures in this world? And being aware enough to say, ‘OK how can I use my influence to impact this?’”

Last year, Weaver completed phase 1 and 2 of the African-American Student Initiative, a cultural proficiency training through the Michigan Department of Education promoting cultural diversity, equity and inclusion. Previously she has been a trainer in a grant-funded position in her district.

“I love doing this kind of facilitation and teacher development, just being able to look at curriculum and pair it with these kinds of experiences and knowledge, because our curriculum is so lacking in alternate views and reflections,” she said.

In one book study session, Weaver shared video of Emmett Till, the 14-year-old Black child from Chicago who was lynched in Mississippi after being accused of offending a white woman. Many were unfamiliar with Till’s story, although it happened in 1955—not long ago.

Weaver knew that history as she grew up, and now she also must teach it to keep her own children safe—a 10-year-old son and seven-year-old daughter—especially in light of the continued killing of Black people by police and white supremacists.

“So in the book study I shared the fact that my own great-grandfather was lynched and how that affects families and opportunities through the generations,” Weaver said.

Four high-profile killings of Black people happened just in the first half of 2020 and reverberated throughout the turmoil of last summer—Ahmaud Arbery, Breonna Taylor, George Floyd, Rayshard Brooks.

“These are not distant things. This is part of our history, but some people have the privilege—again, not saying that negatively because we all have privilege in different ways—but some people have the privilege not to think about these things because it’s not going to impact them.”

Now she sees hope in nationwide engagement around systemic racism. “People are showing up willingly to learn, and they can’t un-see it now. They’re ready to interrupt it and be an advocate or call for change. If this work keeps growing, what impact will we have on the world?”

MEA member Rick Jackson participated in an MEA book study on How to be an Antiracist even though he felt as if he had lived by those principles since high school when his friendship with a Vietmanese immigrant exposed him to racism second-hand.

Now 17 years into teaching math and history at an alternative high school in Kelloggsville, Jackson said the book study has inspired him to facilitate more conversation around the subject in his U.S. History class and in current events discussions with other students at his school.

The biggest takeaway for him was the idea that racism and antiracism are policy decisions. Individuals who are antiracist are actively working toward policies that help promote equity for people of color or those from marginalized communities.

“The book is so clear that it gives me a firmer foundation to stand on in the work,” Jackson said.

Because the subject can be potentially very difficult to talk about, the facilitators of the MEA book study addressed the sensitivity early on, explaining that there is a risk of meaning well but saying something poorly and offending someone, Jackson said.

“If someone did say something that was maybe reflective of older thinking, then it was further discussed but with the idea of let’s be forgiving of each other. Let’s really work to have these tough discussions, because that is how we grow.”

With all that is drawing attention to issues of race in the U.S., students are hungry to discuss it, Jackson said. This fall he has successfully navigated difficult conversations with groups of students even when uncomfortable questions arose around the Black Lives Matter movement.

“We did have one student who said, ‘It should be All Lives Matter,’ and that started to escalate, but we discussed and everyone calmed down. By the end he got it—that we say black lives matter because statistically and traditionally in this country they haven’t. It’s not that only black lives matter. It’s that black lives do matter, and we need to recognize it.”

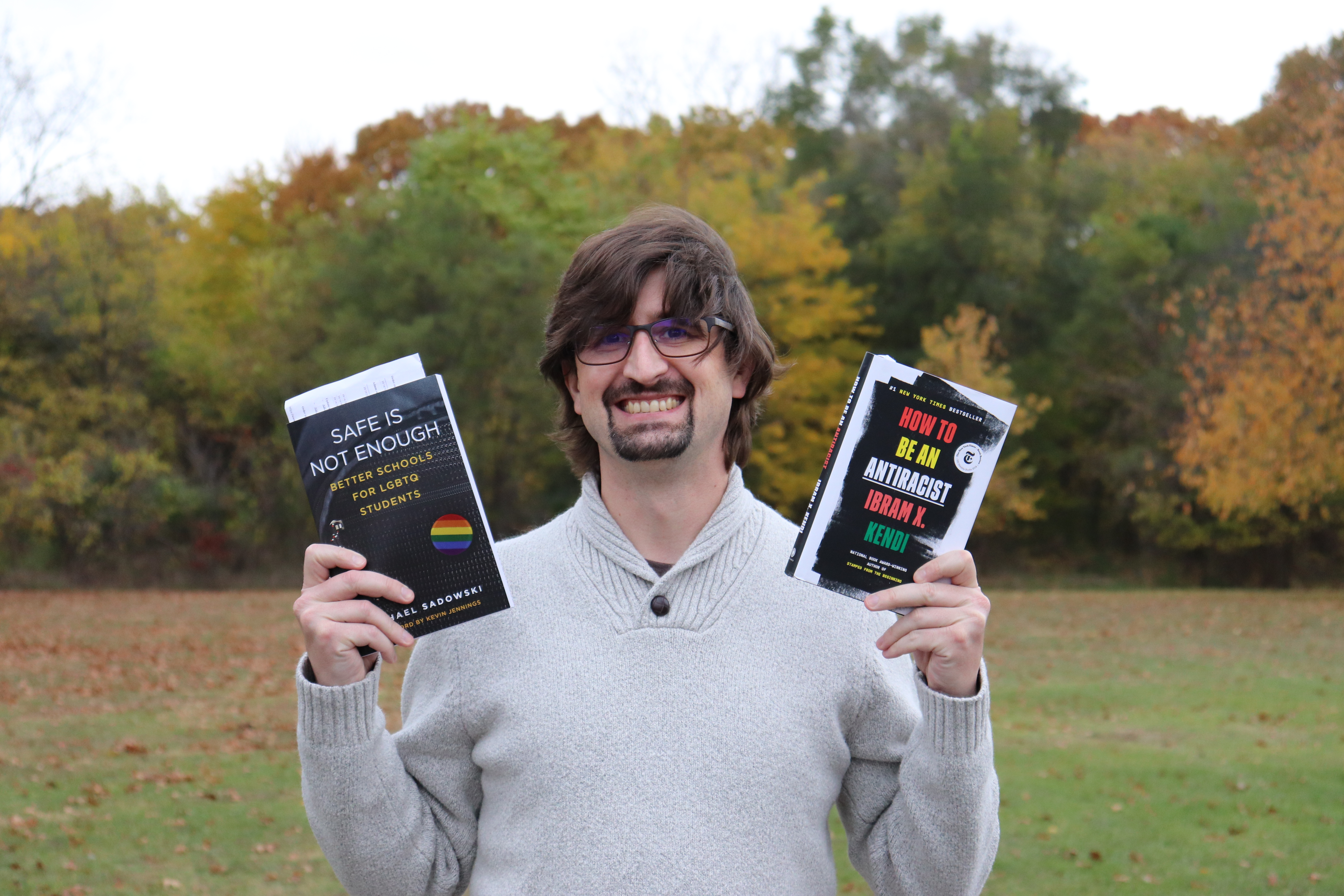

Things didn’t go so well when Jackson tried to have a conversation about LGBTQ rights, he added. That led him to sign up for another book study which started in November—delving into the book Safe is Not Enough: Better Schools for LGBTQ Students by Michael Sadowski. The course is led by teacher-leaders from the MEA LGBTQ Caucus.

Things didn’t go so well when Jackson tried to have a conversation about LGBTQ rights, he added. That led him to sign up for another book study which started in November—delving into the book Safe is Not Enough: Better Schools for LGBTQ Students by Michael Sadowski. The course is led by teacher-leaders from the MEA LGBTQ Caucus.

Like several other MEA book studies in recent months, the Safe is Not Enough offering filled up within hours. People are eager to understand better and do better when it comes to this topic, said Dan Slagter, a Grand Rapids art teacher and one of the session leaders.

“Somehow we are striking gold with these virtual book studies in the middle of the dumpster fire that is 2020,” Slagter said. “The coolest part is seeing educators connecting from all around Michigan—east to west, north to south, urban to rural. That has been incredibly powerful.”

The book is a tremendous resource, because it includes lists of resources and examples of individuals changing their classroom practice to be more inclusive to the benefit of all kids—not just those LGBTQ individuals who may have felt unheard and unseen before.

One particularly inspiring case study follows the example of an English teacher who fought to get approval for a class curriculum that would study the works of LGBTQ writers. The good problem she has now is the class is so popular it has to turn away students, Slagter said.

The book study explores the history and effects of discrimination against LGBTQ people and how to make change. More than 70 percent of LGBTQ youth report experiencing discrimination. They are five times more likely to try suicide than heterosexual youth.

“This book study is definitely an emotional roller coaster,” Slagter said. “We’ve had people crying. We’ve had people literally getting up out of their chair and dancing. Because we try every week to hit on one simple hashtag: Representation matters.”

Slagter said there are good materials for use with all age levels. He uses a picture book, Red: A Crayon’s Story to encourage self-acceptance and belonging with kindergarteners and a book of works by queer writers, The Letter Q, works well in high school.

“In my room, in the most urban of urban diverse schools, I have a policy of we love each other, and we respect and encourage each other,” Slagter said.

The book study includes curricular supplements for each age level, along with resources for dealing with adults aligned against inclusion.

“Sometimes thinking of small ways to incorporate different things, which then build on each other, can make a more lasting impact,” Slagter said. “Maybe you don’t need a big splash when a lot of little ripples will get the job done.”