New MTOY: An Advocate for Educators and ‘Marginalized Voices’

By Brenda Ortega

MEA Voice Editor

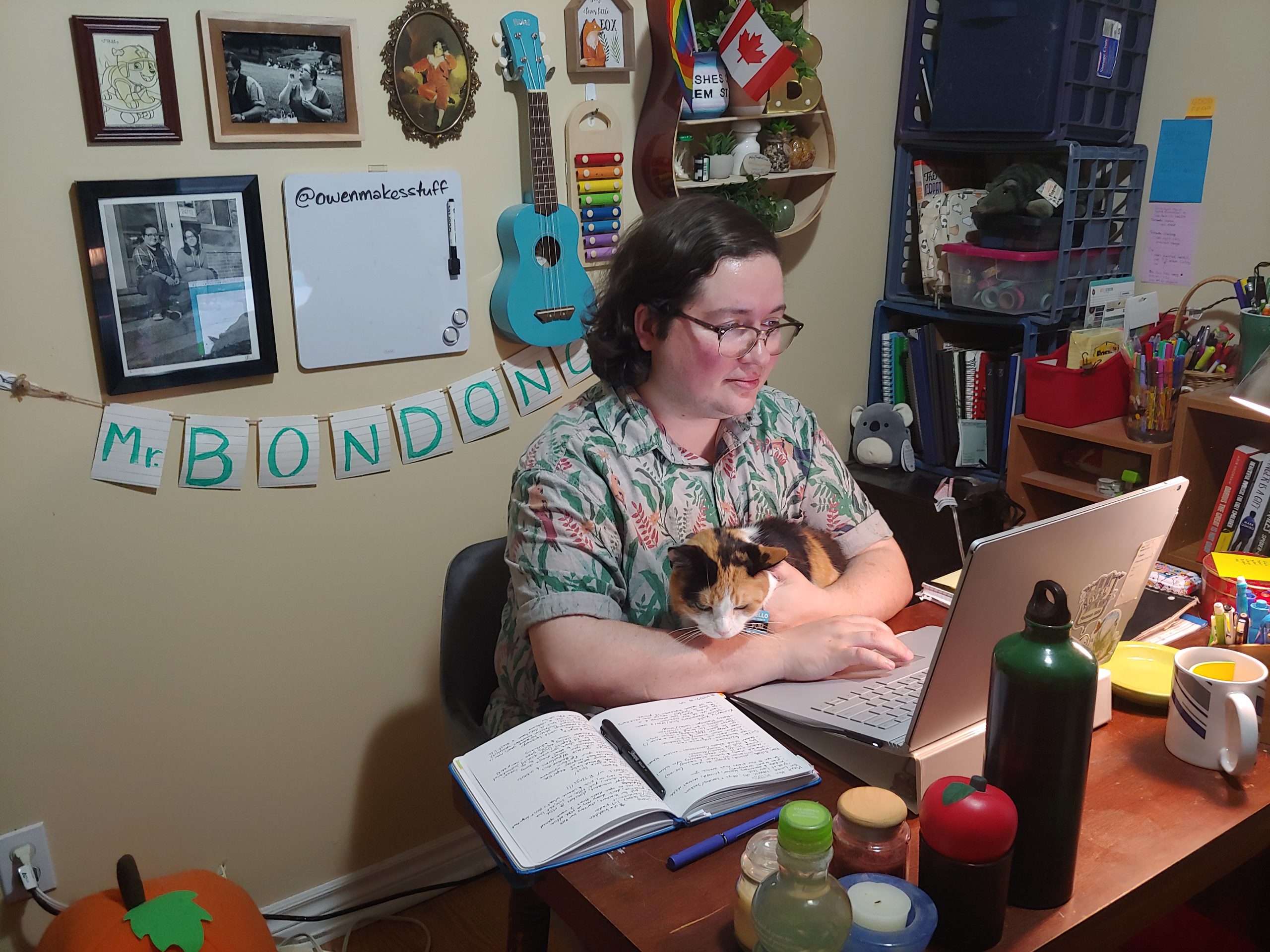

MEA member Owen Bondono quickly got down to work as the new Michigan Teacher of the Year (MTOY).

Just a few weeks into the role as advocate and voice for the state’s educators, the Oak Park language arts teacher began surveying school employees on their thoughts about returning to school amid a global pandemic.

Bondono has sorted educators’ fears into several categories. One concern was repeated again and again, he says: How can a school system that can’t keep toilet paper and pencils in stock be able to supply adequate personal protective equipment?

“There’s a lot of worry about funding and supplies,” he said. “There’s worry about air quality and infrastructure. There’s a lot of worry about schools that are going to disregard anything on the (MI Safe Schools) Roadmap that’s recommended instead of required and essentially go back to school like it’s business as usual with no social distancing, no reduced class sizes, and – depending on the age of students – no masks.

“There’s a lot of concern about teachers being forced to work from their school building even though they’re teaching remotely in areas with high numbers of infections. And I’ve heard a lot of concern about the lack of transparent communication (from administrators).”

On the other hand, many educators are feeling optimistic and creative despite the challenges and concerns, Bondono said.

“They know the circumstances might not be the best, but they’re excited to reconnect with their peers and their students and get back to some sense of routine and normalcy, even though it won’t look like what we’re used to.”

The 31-year-old sixth-year teacher said he plans to take the feedback to the Sept. 8 meeting of the State Board of Education, where the MTOY holds a non-voting seat. The point is not to offer solutions; “There’s no one solution that can make everyone happy,” he said.

“That’s the worst part. We’re all in the same pretty awful situation, but our experience of it will be wildly different depending on our individual circumstances and resources. My job at the State Board of Education is to represent teachers’ voices – especially in a time like now when many teachers are feeling unheard.”

For his part, Bondono worries about ongoing effects of COVID-19 that some survivors are experiencing. “I know somebody who’s been sick for over nine weeks. We don’t know yet what the long-term consequences of this disease are going to be for some people.”

Ensuring safe spaces has always been a focus for Bondono, who has committed to lifting up the voices of marginalized people during his year in the education spotlight.

He is the first openly transgender person to be selected for the state’s top teaching post, recognized for creating an inclusive, supportive classroom where all young people can thrive. The key, he says, is getting to know students on a human level.

He is the first openly transgender person to be selected for the state’s top teaching post, recognized for creating an inclusive, supportive classroom where all young people can thrive. The key, he says, is getting to know students on a human level.

“We can forget sometimes, especially at the secondary level when you’ve got 130 or more students under your charge, that every single one of them is a completely unique individual,” he said.

In his language arts classes at Oak Park’s Freshman Institute, Bondono does narrative writing alongside his students. “We spend a lot of time at the beginning of the year talking about identity, what communities we belong to, and moments that have emotional significance.”

Once bonds are created, he maintains connection by prioritizing open conversation. “Protecting the space is about being willing to stop, for example, if someone makes a joke that is sexist and say, ‘Hey, I don’t think you realize that was inappropriate, so let’s unpack this together.’

“I approach it as a learning opportunity, and students start to learn that they’re safe in my room.”

Even more frequently than their straight, cisgender peers, LGBTQ youth experience hostility, harassment, or violence at school – and sometimes at home, as well. As a young person, Bondono had friends who became homeless after coming out to parents, and he points out that LGBTQ youth are four times more likely to attempt suicide than other groups.

Growing up in Shelby Township, he felt supported in his family but experienced bullying at school. “My mom is a lesbian, and my big sister is also queer, so I wasn’t getting that negativity from my home, but at school it was sort of—what’s the phrase? Death by a thousand little cuts?”

The abuse began with teasing about his mother in elementary school and getting in trouble when he defined the word lesbian for some kids on the playground. “That told me right away that the topic of who my mother is and what my family is was inappropriate for school,” he said.

In high school, where he was out as bisexual (he didn’t come out as trans until college), Bondono was mistreated by students who didn’t want to let him use the bathroom. When he and others tried to start a Gay-Straight Alliance club, the principal denied the request.

“We had a lot of that, where it felt very much like my queer friends and I were huddled together like penguins in the cold, trying to keep each other warm,” he said. “We used to talk about which teachers we thought might be gay. At the time it was just a bunch of teenagers gossiping, but looking back I think it was this deep hope that maybe there were people like us who were adults and had made it through, and we were searching for them desperately.”

For that reason, Bondono hopes to be a “possibility model.” He borrowed the term from transgender actress Laverne Cox, best known for her groundbreaking role on the Netflix series Orange is the New Black.

“That term shapes a lot of what I do in my classroom, because many times our students don’t know how to have these conversations. They don’t know how to express who they are. They don’t know how to stand up for themselves in a way that’s appropriate. So by doing these things in front of them, I’m being a possibility model of what one version of an adult looks like.”

Bondono originally thought he would pursue music when he arrived at Wayne State University as a freshman, but he changed after realizing that all of his interests and hobbies had to do with “helping people grow on their journeys.”

It started with a volunteer role with the non-profit National Novel Writing Month (NaNoWriMo) organization 12 years ago – a position he still holds as the metro Detroit region liaison. The organization encourages writers to produce 50,000-word novels every November, and Bondono helps organize local events.

“Writing has always been a thing I’ve done,” he said. “When I was a little kid and I got in trouble, my mom would make me write out what I had done wrong and what I would do differently next time. She stopped the day I wrote a story about how it was actually the alien’s fault.”

Now Bondono enjoys encouraging students to become readers and writers. He looks for literature that is well-written and relatable, either because the characters are diverse or the situations depicted are universal.

This summer he taught a virtual enrichment class through his school district and had a great experience using a non-fiction title, This Book is Anti-Racist, by Tiffany Jewell. With short engaging chapters and journal activities, the book lent itself to “amazing discussions,” he said.

Educators looking to be more supportive and inclusive toward LGBTQ students should seek out high-quality learning materials, Bondono said. He recommended to start with the Michigan Department of Education’s Safe and Supportive Schools trainings, the guide to Best Practices for Serving LGBTQ Youth from Teaching Tolerance, and numerous resources from the Gay, Lesbian & Straight Education Network (GLSEN). [

He also encourages educators from every subject area to “normalize LGBTQ identities” by teaching about queer people who have contributed to their field. He remembers, for example, studying Walt Whitman in high school and being shocked to learn in college that the 19th Century poet was gay.

“It felt like this whole history of people like me had been hidden from me,” he said.

Inclusion can be as simple as including the information along with other biographical facts – “they were born in this time and in this place and also they were gay,” he added.

“Queer people have always existed, and it helps knowing that you are not some strange anomaly – that the community is not some recent development in the human condition. We’ve always been here, and we’ve always contributed to society.”

In addition to his work on the State Board of Education, Bondono will serve with the nine Regional Teachers of the Year on the Michigan Teacher Leadership Advisory Council and as a member of the Governor’s Educator Advisory Council. He is also the state’s candidate for the prestigious National Teacher of the Year award.