Special ed paraeducators share challenges and needs

MEA member Darrin Watkins has been a paraeducator in Pontiac for longer than he can remember – somewhere around 30 years – and he has a few ideas about how special education could be restructured and resourced to improve services and keep people in the field.

paraeducators need to be successful and stay in the job.

Watkins was among 30 special education paras from across the state who participated in a summer focus group led by MEA President Chandra Madafferi as part of her work on the Optimise Task Force – a statewide group organized by the Michigan Legislature to address special education staffing shortages and improve the talent pipeline.

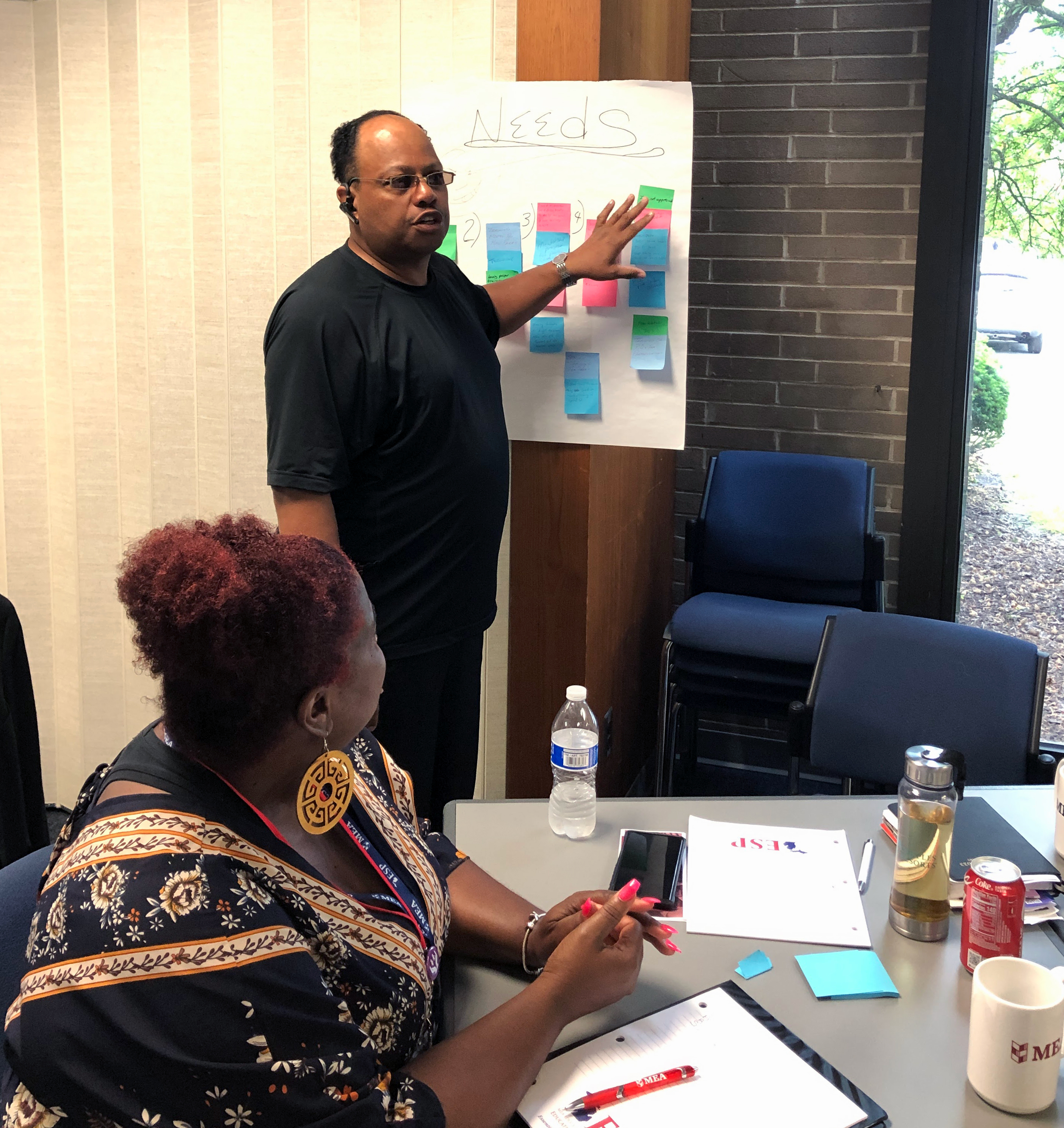

At the meeting – held at MEA headquarters in East Lansing as part of the ESP Statewide Conference in June – Watkins and a small group of colleagues from a few different districts had identified challenges they faced and needs they experienced on the job, and he was reporting out their conclusions.

“So I’ve broken our answers down to five categories, and the top one for my group was money, money, money, more money, and more money,” he said. “The next one is training, mentorship and more education. We need [professional development] that is specific for paras.

“I know in my district we’ll have 20 paras sitting in a PD that has nothing to do with paraeducators or special education, and that’s just a slap in the face,” Watkins said.

The focus group was one of several that Madafferi is conducting alongside Dr. Peggy Yates, an associate professor and director of Special Education Preparation at Alma College. The two will present their paraeducator-related findings to the larger task force later this year.

In discussions during the four-hour session, participants consistently identified low pay, lack of training, no preparation time, and little understanding of the importance of their role as challenges that lead to high turnover in the profession.

In addition, they said, paras are regularly excluded from meetings and other communications about students or even from knowing about students’ Individualized Education Plans, which detail accommodations that are mandated to be provided.

“Treat our job as a career,” said Amber White, a paraeducator in Reed City and vice president of her local union. “I’m in my tenth year; I subbed for two years before that. I have no desire to go into the teaching field – I want to stay a para. But I want to be respected as that para.”

Training is needed to teach paraeducators not only how to better care for and educate students with special needs but also how to de-escalate behaviors among students with trauma in their backgrounds or emotional impairments to avoid injuries in the classroom, the participants said.

“Just like in nursing,” Madafferi summarized, “where the RN nurse works closely with the LPN nurse and they rely on each other – our teachers and paraeducators work closely together, and they each need the pay and training and respect they receive to reflect that. We need to think of our profession as a whole.”

The Optimise Task Force, made up of representatives from numerous education stakeholder groups, is expected next year to recommend rule changes and legislative remedies among other proposals in a multi-year action plan to attract, prepare, and retain qualified personnel for children with disabilities.