Wayne-Westland union’s win took twists and turns

By Brenda Ortega

MEA Voice Editor

If you follow the news, you might recall a huge budget crisis that burst on the scene in the Wayne-Westland School District as winter holidays approached 18 months ago, suddenly prompting threats to privatize busing and lay off dozens of employees.

If you follow the news, you might recall a huge budget crisis that burst on the scene in the Wayne-Westland School District as winter holidays approached 18 months ago, suddenly prompting threats to privatize busing and lay off dozens of employees.

You may remember the local union mobilizing resistance to shut down both the outsourcing and most cuts to the workforce, despite the district’s dire warnings of a $30 million budget shortfall.

After that you possibly saw an occasional news report in April as teacher contract talks began, in June as the district discussed budget-cutting and applied for a state loan, or in August and September as the school board parted ways with the superintendent and considered closing an elementary school.

There’s a chance you caught wind of contract negotiations moving to state mediation last November. But you would have had to dig deeply to find the saga’s dramatic conclusion in January— even though it represented a stunning reversal of fortunes.

After turning down repeated concessionary offers from administration, the Wayne-Westland Education Association (W-WEA) won steps and salary schedule increases of 12% over three years—and more.

The district paid back the loan, and its fund balance after the contract took effect stood at $24 million.

You might’ve wondered how the district’s financial picture changed drastically in such a short time. But you wouldn’t have found the answer—that the district never had a deficit in the first place.

Until now, the story has not been told of how the union won big in the face of seemingly insurmountable odds, an incredible tale of union expertise, connection, and relentlessness.

“Everybody came together, because that’s what you do in Wayne-Westland,” said Tonya Karpinski, the MEA executive director who serves the unit. “It’s in the union culture that’s been established.”

W-WEA President Steve Conn agreed: “Here we have true solidarity and a union coalition where everybody has each other’s backs.”

As soon as the crisis began in late fall of 2023, the unit’s experienced bargaining team questioned the district’s budget numbers and outlined a plan of action. Step one: Stop privatization. Step two: Stop layoffs. Step three: Figure out finances to prepare for bargaining.

STEP ONE

In 2008, when the last teacher strike in Michigan happened in Wayne-Westland schools, aides, custodians, secretaries and others from support staff units refused to cross the picket line. Now teachers and other certificated staff stood alongside transportation employees.

Drivers met with Karpinski and Conn who urged them not to leave for other districts, which would have made privatization inevitable. “My job was to rally the troops,” Conn said.

“When the bus drivers were asking, ‘Should we retire? How are we going to buy presents for Christmas?’ I was there to say, ‘We will show up for you.’ And we did—100%. We rallied around them, and it was a beautiful thing.”

In addition to its own members, the W-WEA called upon other unions that November and December, especially the United Auto Workers. School employees from Wayne-Westland had recently stood on local picket lines during the UAW’s historic strike in September and October.

“Local 900 is a UAW assembly plant that was part of the rolling strike that happened through that summer, and W-WEA was assigned a gate to picket every Friday,” Conn said. “They knew we had their back, so when we started picketing school board meetings, 100-plus UAW members showed up. You don’t see it much anymore, but we have a true union coalition.”

Hundreds of community members began turning out for meetings, which moved to the high school auditorium, and the pressure ratcheted up quickly, Karpinski said.

Talk of privatization had begun not long after a shocking financial audit was shared at a sparsely attended October school board meeting indicating the district’s fund balance had fallen from 24% the previous year to 6% without warning.

At meeting’s end, the board president mentioned outsourcing transportation, but no vote was taken. The next day, when the superintendent and human resources director called to say they planned to seek bids for the job, Karpinski warned: “Don’t do this. This will not be good for either of you.”

It wasn’t a threat, she said, but advice for district newcomers she perceived as not understanding the community: “I was telling them what I was going to have to do: I was going to have to mobilize.”

Weeks later in December, amid a community firestorm, the school district walked back the plan to privatize jobs of bus drivers.

STEP TWO

A key to the W-WEA’s power is the loyalty and responsiveness of members. Despite so-called right-to-work and other union-busting state laws passed by a Republican-controlled Legislature and governor in 2012, the unit’s membership has never fallen below 90%.

“When we say, ‘We need you to picket,’ they picket,” Karpinski said. “When we say, ‘Wear red,’ they wear red. When we say, ‘Show up to the board meeting,’ they show up.”

The union’s goal was to address the financial problem in bargaining, not in panicked cuts and layoffs by the board. To win, the message had to be clear and the membership had to be unified, said Chris Kozaczynski, a second-grade teacher who’s been on the bargaining team for 18 years.

“Our members trust us at this point,” he said. “You build that over time.”

The message hammered on how the district went from a healthy fund balance to a deficit in a year’s time without officials realizing what was happening, that clear answers were needed so solutions could be developed, that staff—and the students they serve—should not pay the price.

Every week, 500-600 people turned out at board meetings. Back in October, the bargaining team had expected the district’s audit to show a general fund balance well above 15%, the threshold for members to receive a 1% bonus in the last year of a two-year contract.

Instead the union found itself offering board members a stopgap to avoid cuts: use $26 million of unspent federal COVID-19 relief dollars to fill the hole and buy time. The alternative gave board members a handhold to grasp, said Timothy Sullivan, a 17-year bargainer and fourth-grade teacher.

“Sometimes we assume the school board is knowledgeable about the district’s finances, but you find out really quickly they’re not,” said Sullivan, one of a few team members who’s become expert at combing through budget line items and financial reports. “The COVID money helped them see a way through this.”

Amid the uproar, two school board members resigned; replacements were appointed; a new board president was chosen; and a new board majority began questioning decisions that led to the crisis.

District officials sent pink slips in early December as notification of a plan to lay off 39 employees including teachers, secretaries, social workers and custodians. But on the eve of winter break, Dec. 21, the school board voted NO on proposed staff cuts by a unanimous 7-0 vote.

STEP THREE

Two truths centered the bargaining team: School audits are only as accurate as the numbers provided by the district, and Wayne-Westland schools should have been in a strong financial position.

“We started looking at revenue, and they planned on getting $125 million that year but they actually got $133 million,” Sullivan said. “They got significantly more money than they planned on getting, partially because the state increased revenue.”

On the other side of the ledger, spending totals appeared out of whack, he said: “For total expenditures, they planned on about 120 (million), and they spent just over 148—so $27 million more than what they originally planned. Isn’t that amazing?”

The union raised red flags, said Kevin Marchi, a high school Spanish teacher and the bargaining team’s longest serving member at 20 years. “It’s a puzzle where you have to put pieces together to solve it.”

The team’s history helped them find discrepancies, added Kozaczynski: “Based on what we’ve seen in previous years, we asked questions. If they didn’t have an answer, we started digging.”

Given more data, the group found accounting errors such as double-counted charges and math miscalculations, even as district leaders blamed the troubles on teacher salaries. Despite the team’s reassurances, rank-and-file members worried they had caused the district’s woes.

“These people are dedicated to Wayne-Westland, so they’re upset and asking, ‘Could I have caused this?’” Marchi said.

The previous contract had ended years of educator pay freezes by bringing individuals up to the salary schedule step reflecting their years of service, resulting in large raises for some. The move stemmed an outflow of teachers to other districts; it didn’t cause the crisis, Sullivan said.

Now the crisis was spurring historic numbers of retirements from educators worried about possibly reduced compensation for pension calculations or loss of contractual payouts for unused vacation days, including the W-WEA’s own longtime president, Don Harris.

“The big thing that frustrates me is how often unions are perceived in a negative connotation by people who think we’re trying to get as much as we can. Our goal is to protect the district. It doesn’t benefit me or a bus driver or any employee for the district to go bankrupt.”

By June, the union had calculated a $32 million general fund balance but couldn’t convince the district its $9 million balance was wrong. Officials took a $30 million state loan and talked of closing a school.

The union had to prove the facts, said Carl Lowe, a middle school teacher who says he’s the bargaining team “baby” as a member for just four years. “That’s when the fourth-grade teacher came out; Tim started teaching math with beautiful colored charts and highlights.”

By August, the superintendent resigned. In September a new finance manager confirmed the $32 million fund balance. The union suggested how to pay back the loan without getting hit on interest.

IN THE END

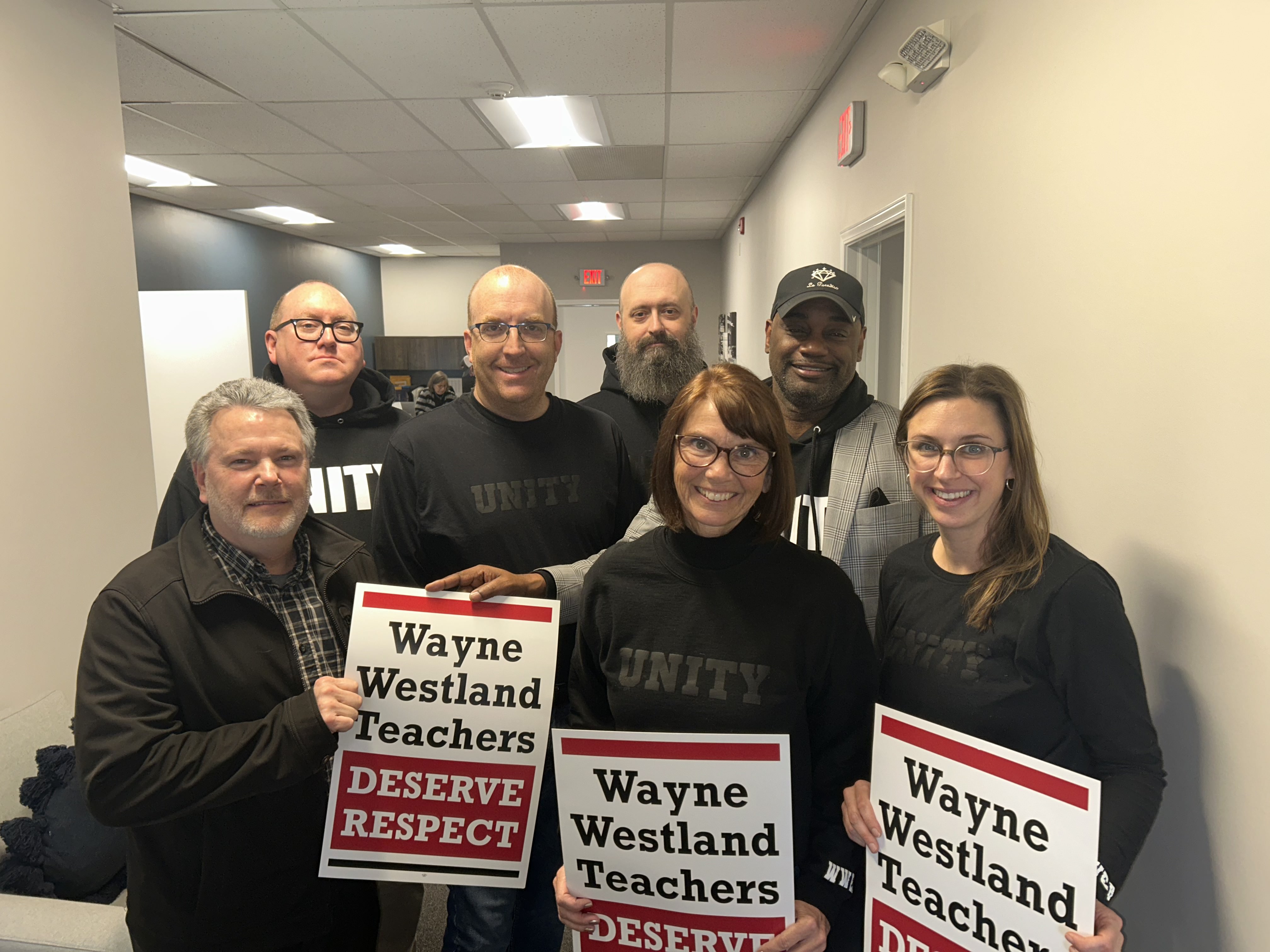

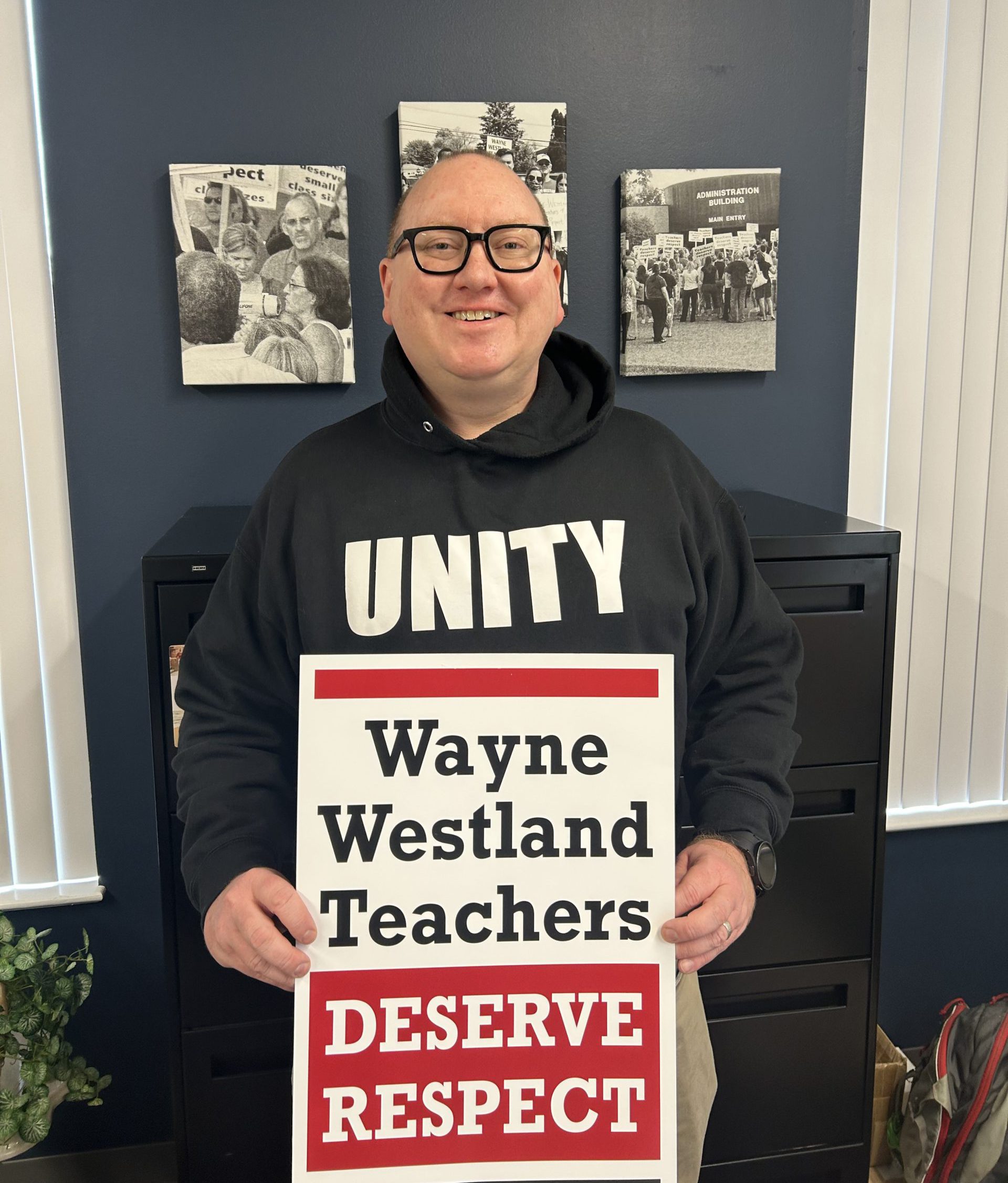

With district spending no longer in the red, the W-WEA had members wear black “Unity” shirts to school and adopted the AC/DC song “Back in Black” as their theme. The bargain wasn’t done.

Karpinski said, “I always tell my members we can prove they have the ability to pay, but it still comes down to willingness to pay. We didn’t take the district’s final offer. We had to do a lot more picketing and a lot more board meetings.”

In January, the mediated settlement won ratification by members in a historic 99.9% vote of approval.

Through the long process, the bargaining team’s close-knit bonds became tighter, evidenced by the jokes and laughter when the group is together. Many are proud Wayne-Westland alumni, and that’s also what makes the work of negotiating contracts a joy, they said.

“These aren’t just numbers we’re looking at; it’s people’s lives,” Sullivan said. “We all want to ensure we take care of the students by taking care of the employees, because they’re the people working with those kids. The biggest thing is you want to leave something positive behind.”

Marchi agreed: “This is our legacy, helping people and ensuring the district remains strong and stable.”

Editor’s Note: This story corrects a version that appears in the April-May print edition of MEA Voice magazine in which the duration of the union’s previous two-year contract was incorrectly identified and the timeline of defeat for a busing privatization plan included an erroneous date. We regret the error.