Book challenges show need for policies to ‘uphold a constitutional promise’

Part 3 of our 5-part “Freedom to Read” series

By Brenda Ortega, MEA Voice Editor

Michigan Education Association

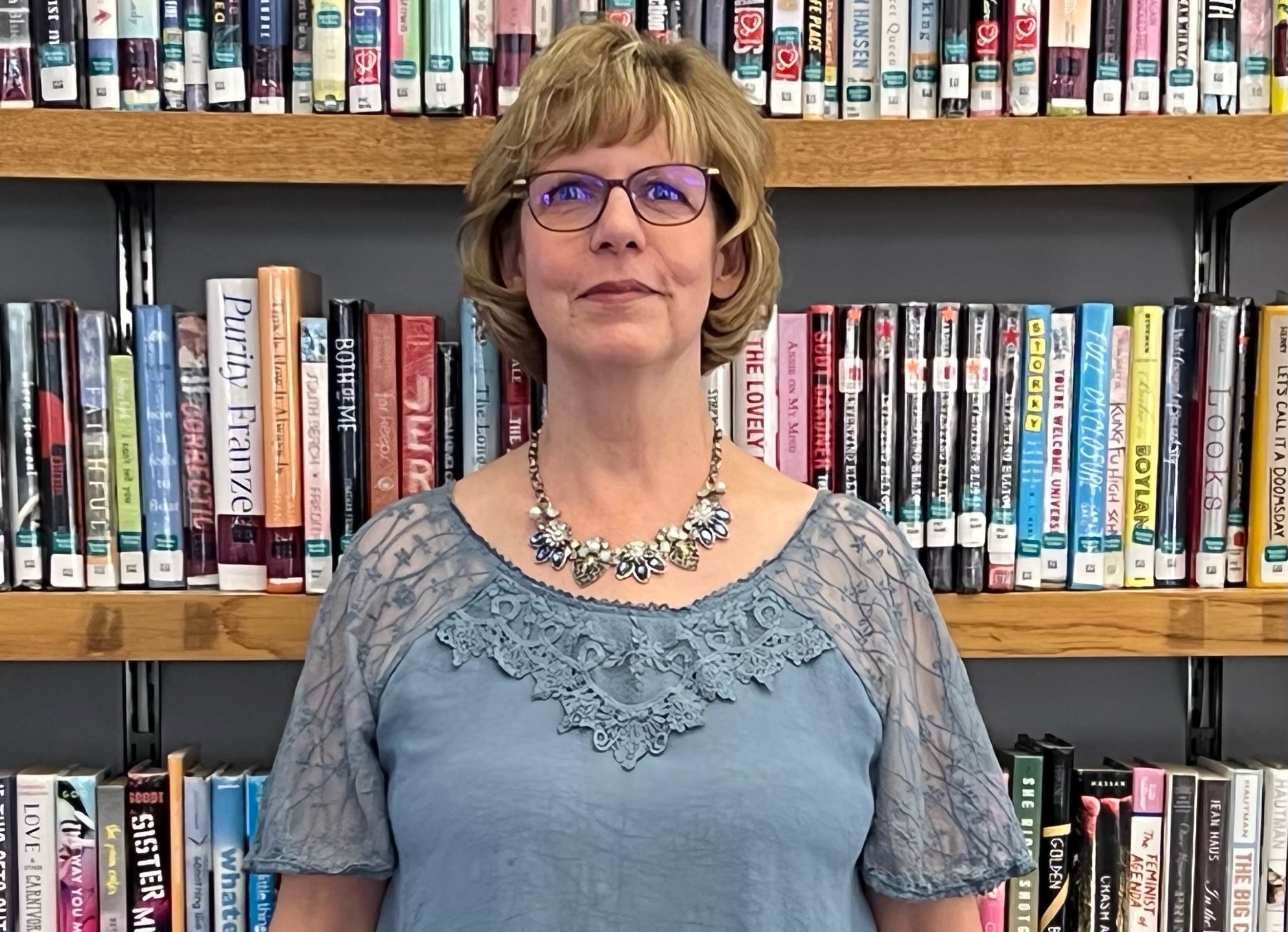

MEA member Christine Beachler has felt especially valued this year in Lowell Area Schools, east of Grand Rapids, where her expertise and well-established library policies and procedures have served as a bulwark against a sudden burst of book removal demands from a small number of people.

The only certified media specialist in the district, serving K-12 libraries in all six Lowell school buildings, Beachler recently received a care package of gift cards from a group of parents expressing appreciation for her professionalism in the face of great difficulty over the past several months.

“It was mind-blowing—I cried. It’s not about the gifts; just the nice comments and emails and messages of support have been really wonderful this year. I’ve received tons of positive feedback from parents thanking me for providing materials for their children.”

Nationwide free speech advocates are documenting a coordinated movement to ban books from school libraries that is “unparalleled in its frequency, intensity and success,” according to PEN America, an organization of writing professionals committed to freedom of expression and access to ideas.

In a report last month PEN America reported 1,586 instances of books being banned from school libraries in 26 states between July 1, 2021 and March 31, 2022, despite polls that consistently show more than 70 percent of Americans oppose banning books that some people find objectionable.

Book bans in Michigan have also increased drastically – to unprecedented levels – so it’s important for school districts to ensure they have professionally aligned reconsideration policies in place for reviewing challenged titles before issues arise, said Debbie Mikula, executive director of the Michigan Library Association (MLA).

“Some libraries have not looked at their policies for 15 or 20 years,” Mikula said. “A strong policy is credible, it is transparent, and it builds trust within the processes. You can’t go around it. You can’t just start pulling books off of shelves. These policies uphold the constitutional promise to protect our First Amendment rights.”

In Lowell, Beachler is a 34-year educator who has spent 20 of those years as a certified media specialist, and she stresses one point: her job is to serve the reading and learning needs of all children.

Whether they are LGBTQ and seeking to find relatable experiences reflected in a story, or their parents wish to shield them from books containing violence or sexual references – and everyone in between – every student in the district deserves to find engaging, relevant books to read, she said.

“I had a parent that said to me, ‘Do you have anything with Christians in it?’ So I showed her how to do a search and find 660 titles we have that contain the word Christianity or Christian. It’s important to acknowledge that librarians operate from a position of neutrality in all of these situations.”

Certified librarians adhere to professional standards for developing library collections and responding to book challenges. Titles are selected based on recommended audience and professional book ratings and reviews, combined with the librarian’s judgment of readers’ and community needs.

Parents can protect their children from any material they find objectionable by asking in writing to restrict particular titles, genres or content from their students’ access, Beachler said.

“Very simply we have a process in place where we will make a note on the students’ accounts that they are not allowed to check out certain books or types of books, and it works beautifully.”

Right now, she pointed out, the district has zero restrictions in place on any of its 4,000 students. Instead, those people with complaints about various books being available in the library have bypassed the first safeguard in place for parents to exercise their right to restrict content.

“I respect their opinions, and I respect their right to parent their children, and I very much respect that they know what’s best for their kids,” Beachler said. “The problem comes in when those same parents want to restrict titles for other people’s children.”

Problems also arise when people object to books they haven’t read, based on internet lists, and go straight to the school board, she added. The district’s formal process requires complainants to read the book and fill out a form, which triggers a committee review.

While the presence of strong policies has helped the district to weather the storm over reading materials, Beachler has had to withstand particularly awful threats by at least one person interested in removing library books.

“I did have a community member who posted online that I was a child sexual abuser and they were going to start a movement to have a citizen’s arrest done on me for providing pornographic material for our kids.”

While painful, the incident underscored her worth and strengthened support she felt from administrators, colleagues and the community, she said. “This has brought our profession into the limelight and made us more appreciated because the work we do is very, very important.”

Protesters in Troy also involved law enforcement in complaints about books.

A flurry of challenges in the Troy School District in northern metro Detroit has been punctuated by community members filing police reports and taking complaints to the city council in addition to submitting formal requests to the district for reconsideration of particular books.

In one case a parent filed a police report claiming an image in the 2006 illustrated memoir, Fun Home: A Family Tragicomic by cartoonist Alison Bechdel, was pornographic. The memoir is not required reading in the district and had been signed out three times in six years when it was challenged.

The story focuses on the author’s youth, her realization as she grows older that she is gay, and her difficult relationship with her closeted father who is an English teacher and funeral home director. The book made several best-of-the-year lists and was a finalist for a National Book Critics Circle Award.

District leaders in Troy have followed formal procedures to address four book challenges submitted in writing while the small group of protesters continued appearing at board meetings to read excerpts from books they dislike.

“When a formal complaint is submitted, a committee is formed to review the book comprised of librarians, teachers, administrators and a parent and/or student when appropriate,” said MEA member Toni Isaac, Troy High School media specialist.

Outcomes of the four book reviews in Troy encapsulated every possibility: Fun Home is restricted to sign-out for students 18 and up or by parent permission; All Boys Aren’t Blue remains available for check-out; Jack of Hearts (and other parts) was removed; and ttyl was moved to the high school collection from the middle school.

For Isaac, the mix of results showed the process works. “None of the votes went 100%, but all were a definite majority. Everyone on the committee read the book in its entirety, we looked at book reviews, and considered how the book did, or did not, fall into the categories protected by our selection process.”

Months earlier, in nearby Novi Community Schools, the book Lawn Boy – an award-winning semi-autobiographical novel featuring a Latino protagonist and themes of class distinction and cultural discrimination – was removed from library shelves after a parent complaint.

The incident alerted school leaders to the absence of a clear district policy for responding to book challenges, and procedures have since been updated to reflect best practices, said Bethany Bratney, media specialist at Novi High School for 13 years.

“The message I have been trying to share with anyone who is willing to listen to me is proactivity,” Bratney said. “No fault to administrators, who have had so much on their plate these last couple of years, but we should get these policies in place before issues arise.”

Books from diverse perspectives – portraying individuals from all walks of life – help students not only to see themselves reflected back but to enter into and understand the perspectives and experiences of others, said Christina Chatel, a middle school media specialist in two Troy schools.

In Troy, home to a large population of students of Indian descent, students were excited when the middle school media centers hosted Michigan author Supriya Kelkar to talk about her 2020 novel, American as Paneer Pie, which explores how an Indian-American girl navigates prejudice in her small town, Chatel added.

“Many students were so excited to read this ‘mirror’ book and to finally see a main character with whom they could relate,” she said. “The book became so popular after our virtual author visit that it was voted by students into our top 10 titles in our annual Troybery reading program.”

The uptick in book challenges and bans in Michigan has spurred the Michigan Library Association to launch a coalition-building effort – MI Right to Read – aimed at bringing together supporters of intellectual freedom to focus attention on the right to read for all of the state’s residents.

The coalition offers toolkits for school and library leaders to ensure they have strong policies in place, as well as resources for community members to get involved in efforts to protect students’ freedom to read diverse literature.

“Libraries fill a role in upholding rights that are guaranteed by the First Amendment of the United States and central to any functioning democracy: the rights of citizens to read, seek information, and speak freely,” the MLA’s Mikula and two others co-wrote in a recent Bridge Michigan op-ed.

“In the spirit of that role, we owe it to every community member to provide material of interest to them on our library shelves.”