Finding Strength in Solidarity

By Brenda Ortega

MEA Voice Editor

MEA member Eric Curtiss thought he had a high number of students in his English classes last year when his numbers topped out at 144. This year he has 168, although the number fluctuates.

Last year he had five preps, the most in his 22-year career. Now he has eight different courses to prepare and teach. “So I have three English classes. I have a psychology class, two journalism classes, and a study skills class. Wait, is that eight? I think that’s seven. I’m missing something.

“Oh, and a reading skills and strategies class. Eight preps.”

Curtiss is employed by Galesburg-Augusta Community Schools, but he teaches in KRESA Virtual & Innovative Collaborative (KVIC) which is a virtual learning program operated by the Kalamazoo Regional Educational Service Agency with participating districts in the region.

The collaborative is the subject of several Unfair Labor Practice (ULP) charges recently filed by MEA for outsourcing the work of bargaining units and violating the terms of local contracts.

The school year had just begun for Curtiss, president of the local union, so he was learning the ropes. “It’s pretty constant electronic communication, either email, phone calls… I’ve even done text messages. I’ve recorded audio and video communications, and it’s week two.”

Eight preps are not allowed under the contract in Galesburg-Augusta. In addition, Curtiss was told he would mostly be teaching local students, but the majority come from neighboring areas.

The KVIC was formed by various Kalamazoo County superintendents who decided to work together on developing a virtual option, said MEA UniServ Director Melvina Gillespie.

The union was completely left out of discussions as the group of administrators decided to tap into the experience of Gull Lake Community Schools, where an in-district virtual school had operated for more than a decade, Gillespie said.

“They basically said, ‘Why don’t we just pay a fee to Gull Lake and have Gull Lake teach our students from all these other districts?’” Gillespie said.

Most of the teachers in the school are from Gull Lake, but others have been hired to handle the influx of students—including Curtiss, who took the position because it was his only option for working remotely and only with a guarantee of returning to his old job next year, she added.

“Just because they’re using technology to deliver the instruction does not allow the districts to outsource the teachers who deliver that instruction,” Gillespie said.

Outsourcing of teaching work has sparked several ULPs in that region, and at press time more waited in the wings from other areas depending on the outcome of ongoing talks between local unions and administrators.

The issue is one of many being fought across bargaining tables, detailed in formal complaints, or aired on picket lines. Meanwhile, educators quitting or taking paid or unpaid leaves under a temporary COVID‑related federal policy are sparking concerns of worsening educator shortages.

Grievances have been discussed and filed over unilateral calendar changes and overwhelming workloads. In Brighton, teachers picketed over the Board of Education’s demands that they accept a nearly 6 percent pay cut despite the district’s 10 percent fund equity balance.

MEA member Becky Rapp, a special education teacher in the district, told news reporters, “I spent over $500 on plexiglass for my classroom, and this feels like a slap in the face.”

In Port Huron, union members spent Labor Day picketing to call attention to their concerns over inadequate supplies and planning to ensure student and staff safety. On the first day of school, they documented more than 80 health and safety concerns in a press release.

“Safety must continue to be our first priority, and the simple truth is Port Huron Area Schools was not prepared to safely resume in-person learning this week,” PHEA President Cathy Murray said in a statement to the press.

In Grosse Pointe, the association sent out a press release and leaders were interviewed on local media after the district put forth a plan for returning to face-to-face learning that glossed over the details of safety protocols.

Community concerns soon forced the district to pivot to remote learning to start, said GPEA President Chris Pratt. “We kept hearing throughout the process from the administration, ‘Let’s not get into the weeds here.’ And the union has been that voice to say, ‘No we actually need to be in the weeds.’

“What I try to make clear every time we go for an interview or put something on social media is that our teachers’ working conditions are the students’ learning conditions.”

The GPEA has become much more active in recent months, building relationships with the local business community and staying vocal about issues that matter, Pratt said. “We’re interviewing candidates for our Board of Education for possible endorsements. With several seats up, that will be significant. This activism, this organizing, is for the betterment of our kids and our staff.”

One issue that has emerged—along with the ubiquitous problem of trying to ensure all students have access to technology and wifi—involves policies around use of sick time when staff get symptoms or must quarantine, said Peter Tyson, president of the Saginaw Township union.

Tyson raised the issue in a call with MEA staff and U.S. Congressman Dan Kildee, who requested a briefing with educators from his district along I-75 from Flint to Bay City. “Younger teachers and teachers with families especially don’t have a lot of sick days to burn. It’s a huge issue for them.”

Andrea Rethman, president of the Saginaw Education Association, also participated in the call with Kildee and questioned whether budget cuts would reduce custodial services already slashed to barebones in many districts, especially in those that have been privatized.

“It was just nice to have his ear and be able to share the concerns that people have around safety and also about trying to get enough technology, because our district is putting up hotspots in every building, but we have Chromebooks and tablets on back order,” Rethman said.

Matt Adams, president of nearby Beecher Education Association, said his district has relied on donated technology from community partners to be able to start the school year remotely. He seconded the point about districts with outsourced services which they do not oversee.

“The truth is if somebody gets sick, if somebody dies, it’s not going to come back on our third party cleaning company—it’s going to come back on Beecher Schools, and that’s a scary place to be,” Adams said.

After the meeting, Kildee called on the U.S. Senate to take up the House-passed Heroes Act to provide schools the resources they need to operate safely this school year.

“While I voted on legislation in May to provide emergency funding to Michigan schools, this critical bill, The Heroes Act, sits on Mitch McConnell’s desk in the Senate,” Kildee said. “We owe it to teachers, students and parents to have a coordinated, fully-funded and whole-of-government response to keep our classrooms safe during the pandemic.”

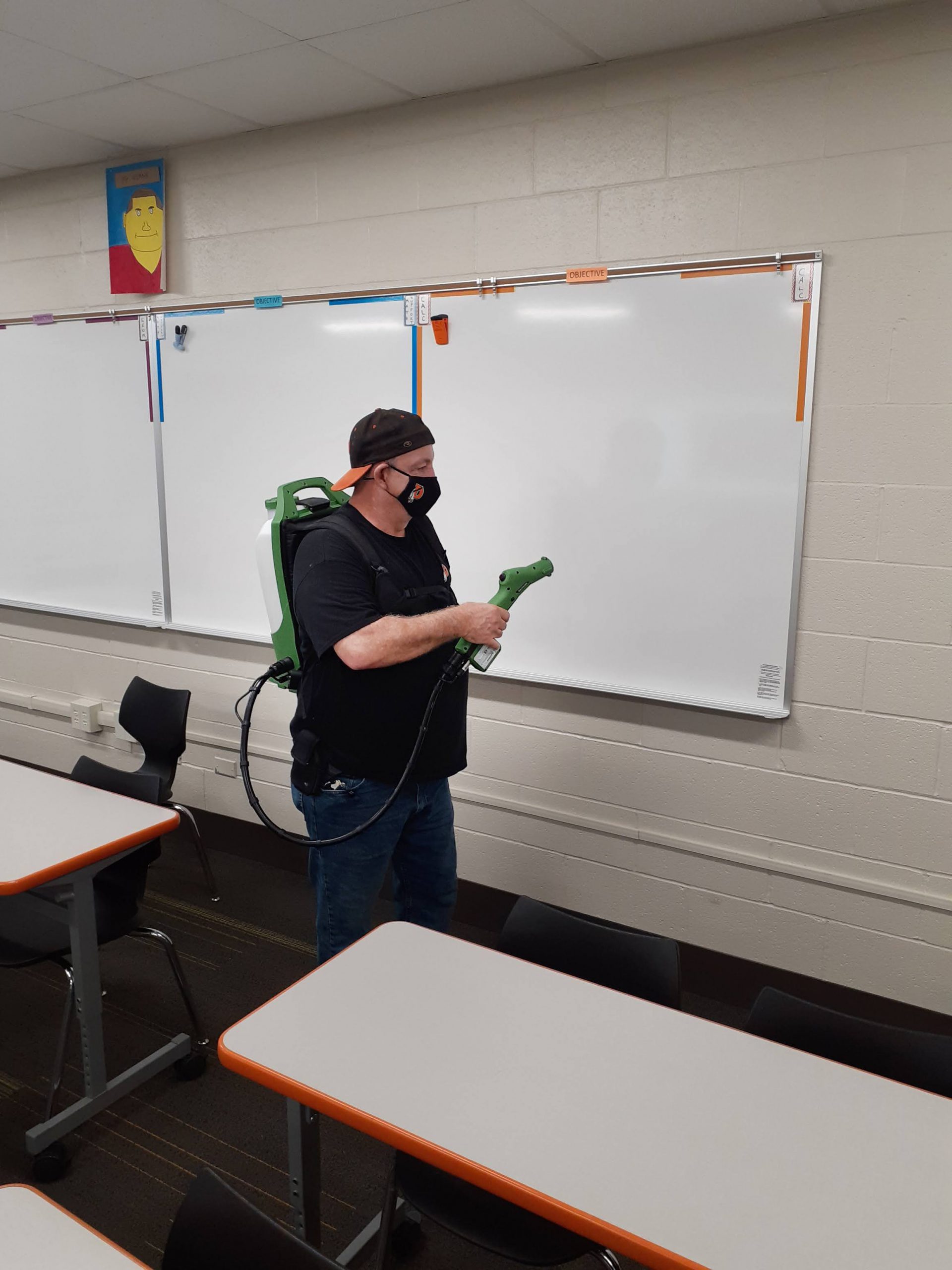

In Dowagiac Union Schools, the district purchased new cleaning equipment for the custodial staff to use, said Roy Freeman, a 34-year custodian and president of his unit. The electrostatic disinfecting equipment imparts a positive electric charge to spray droplets, causing them to be attracted to surfaces like opposite poles of a magnet for uniform coverage.

In Dowagiac Union Schools, the district purchased new cleaning equipment for the custodial staff to use, said Roy Freeman, a 34-year custodian and president of his unit. The electrostatic disinfecting equipment imparts a positive electric charge to spray droplets, causing them to be attracted to surfaces like opposite poles of a magnet for uniform coverage.

“In reality, it takes 10 minutes for a disinfectant to really do its job,” Freeman said. “In most cases when you wipe it on, wipe it off, you’re not getting everything accomplished.”

In addition to his leadership in Dowagiac, Freeman plays an advocacy role for support staff at the state level as an MEA board member and president of the ESP Caucus. He worried about reports he was hearing of impending layoffs of paraeducators in some districts.

“That’s a shame,” he said. “There’s work the parapros can do with the teachers to make things easier, because I’m hearing how much work goes into handling the face-to-face and remote learning at the same time. That’s a lot for the teachers alone.”

In Kalamazoo, that sort of shared interest caused the EA unit of certificated staff and the ESP unit of non-certificated employees to join forces, said Tricia Dinda, a driver and union steward who serves on the bargaining committee.

Employees from various classifications have unique concerns, Dinda said. For example, she noticed face shields the district planned to buy for drivers slipped off when she bent over to buckle a students’ wheelchair in place. The district changed brands in response to her complaint.

But above all, school employees share one big mutual concern: student and staff safety, she said. “It’s a solidarity exercise to say, ‘Hey, I stand with you.’ Knowing that somebody has your back as a union member I think is doubly important in 2020.”