LCC Equity Initiative: ‘A Game Changer’

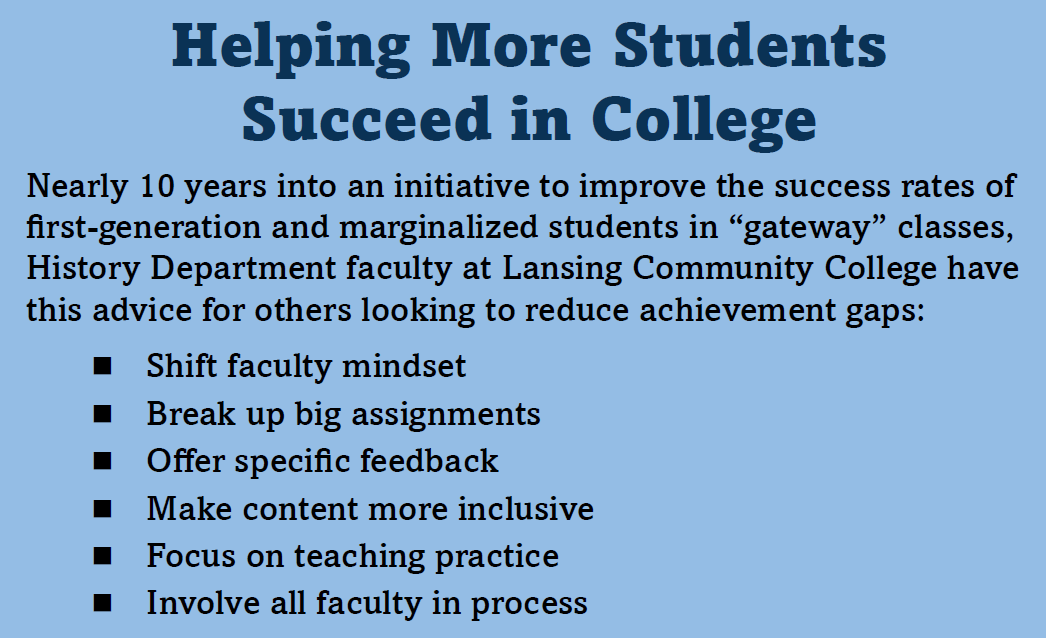

After nearly a decade of equity work focused on improving student success and closing achievement gaps, Lansing Community College History Professor Jeff Janowick has some hard-fought wisdom to share. Some of it, the MEA member admits, may seem obvious.

“The first thing we had to change as a department was our mindset,” Janowick said. “As teachers we often think we’re teaching content and then measuring whether students were successful in learning it. Instead, we had to think about what we could do to help students be successful.

“That seems obvious but turns out it’s a game changer.”

The history department began to face the problem when a college-wide data review and improvement process nearly 10 years ago revealed sizeable achievement gaps for first-generation students and students of color, he said.

For Black students in the introductory history class, in particular, the divide in passing rates compared to other students stood at 20 points at that time, Janowick said. Nearly half of Black students who took the intro-level history class were failing, according to the data.

“We knew we had issues, but I don’t think we knew it was that bad,” he said. “It’s one thing to sort of have a general impression. Looking at the numbers made a huge difference because it was a slap in the face.”

There is no magic solution to fix the problem, but a sustained focus on pedagogy and practice has yielded slow, steady results over the past several years, says MEA member Kevin Brown, one of three full-time professors in the LCC history department.

“What we have found is student success often comes down to trying to make a connection with your students over the material,” Brown said. “If you are going to teach undergrads, you must love your subject, but you also have to be excited about teaching it to others.”

Student success in the introductory history class was especially critical to address because it is considered a “gateway” to college completion— so-called because it is often required to move forward and because students who don’t pass often end up leaving college.

For example, the introductory history class is required at Michigan State University, which is the institution where the largest number of LCC students transfer to complete a four-year degree.

Recognition of the problem led the department to join a college initiative known as Gateways to Completion, targeting student success rates in gateway courses with emphasis on improving the performance of students from marginalized groups.

“At some point we had to recognize this wasn’t just a student problem,” Janowick said. “It means we’re not doing what we want to do—we’re not reaching those students, and we have to change something.”

To make change, the department launched the Best Practice Sessions—a monthly forum on teaching which brings together the three full-time faculty members and several times as many adjunct instructors who also teach the introductory course.

“We made sure our adjuncts were invited and compensated for attending, but more importantly their opinions were heard and respected when we started making decisions about what to change,” Janowick said. “We made sure it was a group conversation.”

To begin with, the sessions addressed faculty beliefs that resist change—those arguments that student achievement issues stem from the ubiquity of cell phones or social media or societal problems— by focusing instead on what is in the control of instructors.

Goals were set to avoid the task feeling unmanageable. “We didn’t start out saying, ‘How are we going to get rid of a 20-point gap?’ We focused on coming up with a 5- or 10-percent improvement in the numbers, which meant helping two more students succeed in a class. And thinking of it that way, sure, I can help two more students.”

Goals were set to avoid the task feeling unmanageable. “We didn’t start out saying, ‘How are we going to get rid of a 20-point gap?’ We focused on coming up with a 5- or 10-percent improvement in the numbers, which meant helping two more students succeed in a class. And thinking of it that way, sure, I can help two more students.”

To start with, everyone shared best practices, “and that led us to a really rich conversation,” Janowick said. One of the struggles of first-generation college students involves their lack of awareness of what to expect from college—and what college expects from them, he added.

With that in mind, one significant change across the department has involved breaking up a small number of assignments that account for big percentages of the final grade. “Sometimes we say students need a wake-up call, but if the wake-up call is 50 percent of their grade—they’re going to be in trouble,” Janowick said.

Along the same line, faculty members have explored how best to give students feedback to help them advance their skills. The old wisdom that said to offer a “compliment sandwich”—tucking a critique between two pieces of praise—doesn’t hold true for students from marginalized populations, he said.

“First-generation college students want direct guidance. They want you to say, ‘Here’s what you need to do to improve.’ It needs to be specific, and I’ve found—if you give them a clear target, they will work to hit it.”

In addition to the “how” of teaching material, the department had to be willing to explore the “what” of course content and whether it was inclusive of marginalized populations. “We still have room to grow, but we have made a conscious effort to make sure we were more representational in terms of the material we taught.”

From there, it’s a smaller leap to an important shift: moving away from multiple choice assessments to more critical thinking and interaction with primary source documents, said Anne Heutsche, the other full-time history professor among the three who rotate leadership duties.

“I ask students to connect pieces of information from different formats and perspectives,” she said. “How are they adding to the conversation or historical narrative? I work to create learning opportunities to develop students’ own thoughts and voices.”

Beyond success in class, students deeply engaged in learning and thinking are better equipped “to navigate the complex and messy world in which they live,” Heutsche said.

The department’s work has increased the success rate of all students and most significantly raised the passing rate of Black students from 52 to 63 percent by 2018, Janowick said. The achievement gap for Black students

dropped from 20 percent to 13 percent.

“There is still a lot of work for us to do,” he said. “It’s slow, incremental change, and sometimes it’s frustrating that there isn’t a silver bullet that makes everything OK. But we just have to remember that this is the work of a lifetime.”

This is a great article and can serve as a model for other disciplines.

Impressive article. Have other LCC units adapted to a similar transformation with like success? If not, what is being done to encourage those units to analyze the efficacy of their current approaches to teaching and learning?