MEA Joins Pilot to Retain New Educators

Meet a few mentors and mentees testing high‑quality supports

MEA member Aric Foster is a National Board Certified Teacher who coaches wrestling and track, works with student teachers, serves as his district’s student-teacher liaison for Oakland University, has taught university courses for aspiring educators—and calls himself “proficient” instead of “master.”

At age 43—21 years into his job as English teacher in Armada—Foster quips that he’s still young and new. He continues to find magic with kids in a classroom and joy in being a “teacher teacher.”

“I love the experience of teaching teaching,” he said. “I’m to the point where I know pedagogy, and I know how to differentiate, scaffold, do formative assessment—all of it. In my role as mentor, I need to know people. It’s that person-to-person connection that really lights my fire and gets me going.”

This year Foster is mentoring a new teacher in the county next door. “I like that it’s union-led and non-evaluative. It’s consequence- free help and guidance—like in the classroom where formative assessment should have zero weight toward students’ final grades. It’s about practice, feedback and learning.”

Foster is one of two dozen skilled, experienced union educators who have stepped forward to serve as a Virtual Instructional Coach in a seven-state pilot program by Midwest education associations, including MEA, known as Educators Leading the Profession (ELP).

The program is piloting teacher-led supports for educators in the first three years of their careers. In Michigan, the 13 mentees are in Farmington Public Schools, and each one picked a coach by combing through written and video introductions. Each is also assigned an in-person building mentor.

MEA member Kathleen Ader was selected as a coach by three new educators. A veteran math and science teacher in Novi, Ader has worked as a high school instructional coach for four years and took on the virtual coaching role because she believes MEA is uniquely positioned to do this work.

“I have been doing some other work with MEA’s Center for Leadership & Learning, and I think the MEA is on an incredible path in terms of all of the programming and professional development they’re offering and the outreach that is trying to make it equitable across the state,” Ader said.

ELP’s coaches were trained on research-based mentoring and expect to address many struggles with mentees, such as evaluation, classroom management, building culture, and work-life balance.

Because the union offers a safe space, mentees can turn for help without fear of bias or evaluation. “It’s probably hard to even measure the magnitude of the importance of that aspect,” Ader said.

MEA member Dan Slagter, a K-8 art teacher in Grand Rapids, said he became a coach because his own mentors were so important to his survival and development early on. “They were incredible, and I still keep in contact with them,” he said.

Being a one-person art depart- ment serving so many students is a tough challenge—especially when new. “The biggest advice I’ve had for [my mentee] so far is to find one little bit of joy, even in the most difficult day, and write it down,” Slagter said.

Educators nationwide are reporting extra challenges with student attention spans, behavior and social interactions this year as the pan- demic stretches toward the two-year mark. Slagter said he’s adapted by continuing to blend in use of video tutorials, because students are accustomed to them.

Focusing on successes maintains positivity, he says, which is important because kids can see true feelings under emotional masks. “Kids sense honesty in that, ‘Yes, times are a little tough right now, but you know what? We’re here. We’re together. We can do it. We just have to help each other.’”

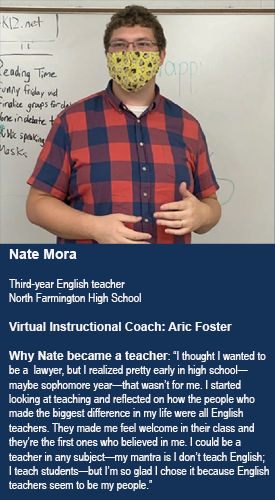

Mentee Nate Mora: ‘Things are always changing’

MEA member Nate Mora knows many veteran educators worry about newcomers to the profession burning out, but he notes that his generation has come of age riding wave after wave of change created at least in part by technology.

MEA member Nate Mora knows many veteran educators worry about newcomers to the profession burning out, but he notes that his generation has come of age riding wave after wave of change created at least in part by technology.

“If you’re comparing teaching now to what it was 20 years ago, it probably looks worse,” Mora said. “But for me—three years into my career— I’ve seen that things are always changing, so I have that mindset: my willingness to evolve with change is crucial to avoiding burnout.”

One silver lining of the pandemic has been school districts’ nationwide nearly universal adoption of a Learning Management System (LMS) of one sort or another, Mora said. This year absences have been challenging for both students and teachers, but now everyone knows how to use an LMS.

“We use Canvas, and though it does take a little bit longer to put everything online, it’s nice when a student has to be out for a week—if they have COVID or whatnot—they know where to go online, and we can stay connected that way.”

Mora is familiar with instructional technology; his first two years of teaching were spent at a blended learning alternative high school in Lansing. His wife’s entry into medical school at Oakland University prompted his move, he added.

Even with his comfort in blended learning, Mora has been happy to return to in-person learning this year. His greatest skill is building relationships with students, he said. “In my experience, the more you are vulnerable with students, the more you open up about your own weaknesses and life experiences, the more students are engaged in your class.”

Now he’s excited to be part of a union after trying to organize a unit at the charter school where he previously worked. “I was gung-ho to be part of the union, and I hope to start joining meetings. I love the support, the community, the knowledge that we’re all stronger when we’re together.”

Being involved in the Educators Leading the Profession pilot program has been icing on the cake. Mora enjoys having a district-assigned mentor who works in Farmington and knows the students and curriculum, but he also appreciates getting an outsider’s perspective from his virtual coach.

He knows that he works in a district with exceptional resources for staff and students, but he appreciates extra help from MEA. “There’s definitely been some difficult days, but I’ve been able to keep up my energy where lots of other teachers I know are struggling, and I think that’s because of all of this support and the people around me.”

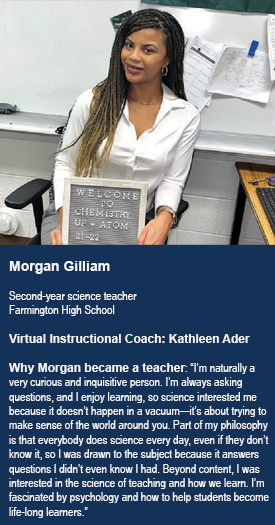

Mentee Morgan Gilliam: ‘I have people looking out for me’

MEA member Morgan Gilliam calls herself a “sponge” who is happy to learn and network with more veteran educators, but in her second year of teaching she’s finding the relationship is more reciprocal than expected because of technological changes brought by the pandemic.

“Veteran teachers are having to go back and figure out a bunch of new things as though they are first-year teachers,” Gilliam said. “It’s interesting because they’re asking questions of those of us who are fresh out of college and fresh out of training—they want our input on some things, too.”

“Veteran teachers are having to go back and figure out a bunch of new things as though they are first-year teachers,” Gilliam said. “It’s interesting because they’re asking questions of those of us who are fresh out of college and fresh out of training—they want our input on some things, too.”

This year Gilliam returned to the district where she grew up, after finishing her first year in River Rouge. Working mostly remotely in her first year left her feeling isolated, although her school community tried to provide support, she said.

“I was trying to figure out a lot of things from scratch, which took a lot out of me; it was exhausting. I realized you shouldn’t be an island. There’s value in building your network and using it as a resource.”

The return of mostly in-person learning this year has helped her feel more connected, but it has brought new challenges—for example, frequent loss of prep time because of the dire substitute teacher shortage.

For her biology classes, a team of several teachers across buildings works together to plan curriculum and assessments and share resources. A smaller group does the same for chemistry, and she’s grateful, she said. “It’s putting more brainpower together into a professional learning community.”

Combined with a district-assigned mentor and departmental resources, being part of MEA’s Educators Leading the Profession pilot program offers an expert outsider perspective she can tap into for whatever she needs or can’t resolve—making her feel surrounded by support.

“I have quite a few people looking out for me,” she said. “And then because I went to Farmington Public Schools, I have teachers that I had as a student who are also holding my hand.”

Her biggest concern so far is in students’ attachment to cell phones, which she worries distracts people from their own curiosity and wonder about the world they inhabit. She’s leaning on her strength—connecting with students and showing she cares—to address it.

Longer term she thinks of structural and funding issues related to public education that she hears veteran colleagues worrying about— and hopes to be part of solutions. “A lot of industries are experiencing sea change, so maybe we can bring about some changes in the next five or 10 years.”

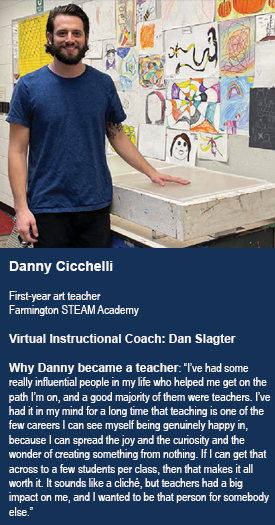

Mentee Danny Cicchelli: ‘You have to adapt as you go’

MEA member Danny Cicchelli is teaching his young students in Farmington to explore in the same way he approaches personal creative projects—from a place of intuition, discovery and expression.

In his first year teaching grades 2-8 at a school focused on Science, Technology, Engineering, Art and Math (STEAM), Cicchelli provides lessons and practice on art fundamentals and techniques—then he offers students materials and a prompt to create with a few examples as guide.

In his first year teaching grades 2-8 at a school focused on Science, Technology, Engineering, Art and Math (STEAM), Cicchelli provides lessons and practice on art fundamentals and techniques—then he offers students materials and a prompt to create with a few examples as guide.

“STEAM has a student-led philosophy, and I’m on the same page with that,” he said. “I give students conceptual prompts and the freedom to approach projects how they wish to. It’s great to let kids explore materials that either they are familiar with and want to master or that are totally new to them.”

However, for a time Cicchelli was spending every weekend at school doing planning, materials prepara- tion, and room set-up. By November, he had to step back—discovering an irony in the process.

“I’ve noticed that giving more time to myself positively affects my teaching. I’m not under-prepared, but I’m able to improvise more and have flexibility. It’s also nice to have time to do my own art, because that will make me a better teacher, too.”

Learning the ins and outs of classroom management has been his biggest struggle. Early on, he had to regroup and establish clearer expectations with class discussions and student input.

It helps to have multiple experienced teachers that he can turn to for advice—from a district-assigned mentor to the Virtual Instructional Coach through the Educators Leading the Profession program and others, although finding time to connect is difficult. A shift in perspective also helped.

“Our middle schoolers switch electives every quarter, so on the last day with two of my classes I thought about how I gave them a really good art class and they seemed sad to leave,” he said.

Cicchelli didn’t discover painting and sculpting until college. His first love was music, but doodling in his notebooks eventually led him to take art classes, where a professor encouraged his talent and prompted him toward a Fine Arts degree at Wayne State University.

He does commissioned work, but much of his own art involves starting with no set plan and seeing what emerges.

“What I love to do is that kind of free, intuitive, psychological type of art and music—and now, teaching is getting wrapped up in that, too,” he said. “You have to know it’s not going to go how you planned and have the flexibility to adapt as you go.