Study finds school reform has left rural communities behind

By Brenda Ortega

MEA Voice Editor

Education policies pursued for the past two decades in Michigan have ignored the needs of rural school districts, which has reduced opportunities for students and stymied community development in areas facing serious economic hardship, a new study has found.

School reforms favored by policymakers over the past 20 years – test-based accountability and school choice – have had a “decidedly urban emphasis,” according to the report from researchers at the Michigan State University College of Education.

“Meanwhile, policymakers in most states have largely ignored educational conditions in rural areas, even though these areas endure some of the country’s most challenging contexts,” the report concludes.

The three-year study analyzed data from all Michigan rural schools and took a deeper dive into 25 diverse and geographically representative rural school districts through surveys, interviews and focus groups.

Led by David Arsen, an MSU professor of Education Policy, the study identified key problem areas that represent the biggest challenges for rural schools and the ways in which one-size-fits-all state policies are poorly aligned to address them.

The problem areas – teacher recruitment and retention, student mental health, broadband access, school funding, and state reporting requirements – were “highly problematic before the pandemic and grew more so during the pandemic,” according to the report.

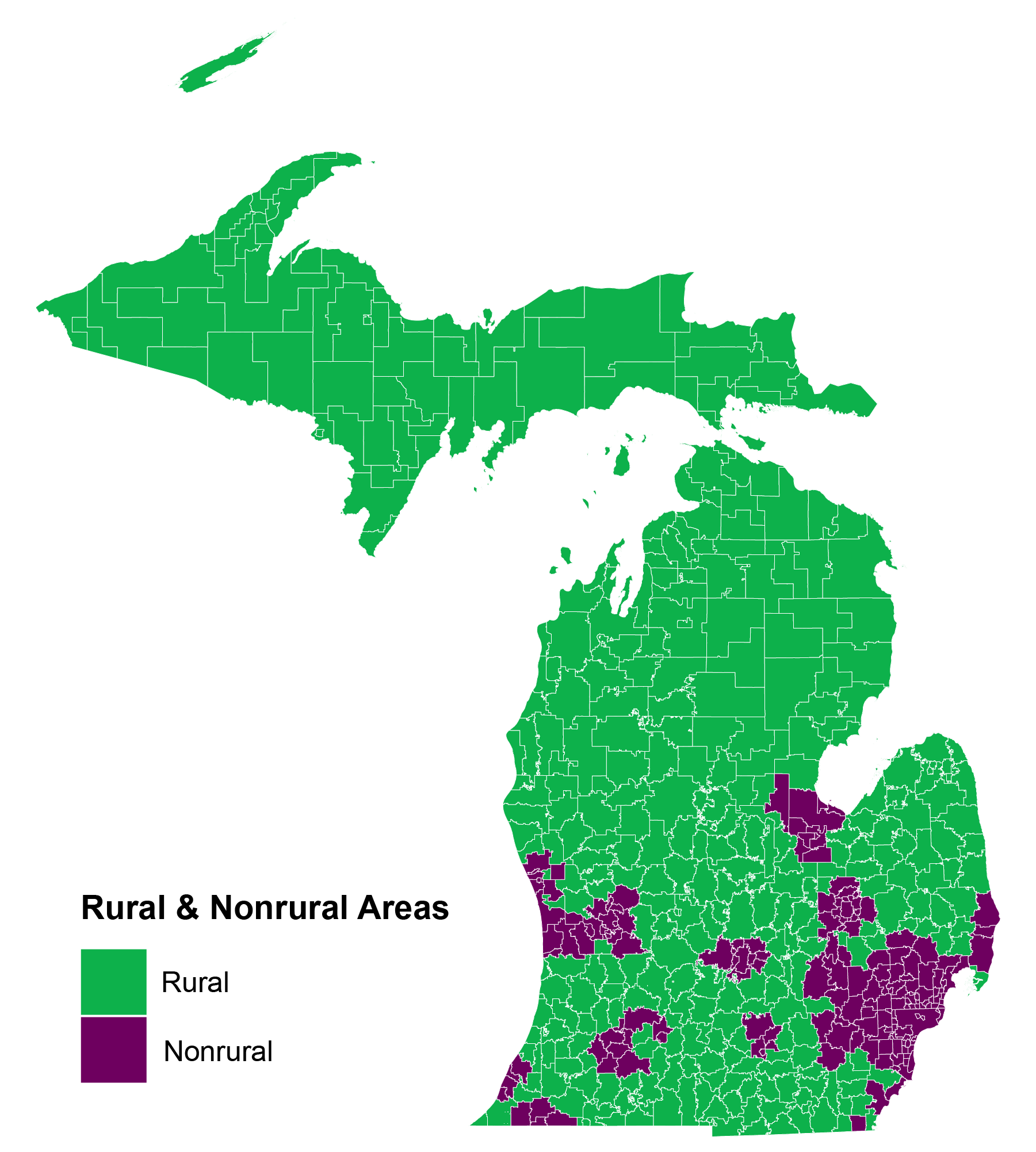

Michigan’s rural school districts comprise nearly 90% of the state’s land area and two-thirds of the school districts, yet they enroll less than one-third of the state’s K-12 students, said MEA Economist Tanner Delpier, a co-author of the study.

Low and declining enrollments mean rural districts experience “diseconomies of scale,” Delpier said in an interview. “For example, if you only have 15 third graders instead of 25 third graders, you still have one class; you still have to pay the teacher.”

In addition, he said, more students in rural districts take the school bus each day, but where suburbs and cities average 137 kids per square mile of district territory, rural districts average eight students per square mile.

The study concluded, “Unless the actual costs of educating students in rural schools are recognized in state funding, students in rural communities will not have equitable access to educational opportunities on par with their peers in nonrural schools.”

Teacher recruitment and retention – among the biggest challenges identified by 80% of rural school superintendents – is a growing issue statewide but represents an especially acute problem in rural districts which today “often receive few, if any, applicants for open teaching positions,” the report said.

“While Michigan was once an exporter of teachers to other states, producing far more educators than our schools needed, now the state leads the nation in the rate of decline in teacher preparation program completers.

“This decline in new teachers far outpaces the decline in Michigan’s K-12 enrollment, which has contributed significantly to a growing statewide teacher shortage.”

Says one superintendent quoted in the report: “It’s my biggest summer nightmare—a massive headache. I cringe every time I get a resignation, or I get a retirement letter, because I don’t know if I’ll ever fill that position.”

Stagnant salaries and reduced benefits, geographic isolation, declining attractiveness of the teaching profession and more stringent certification requirements have all contributed to the problem.

To address it, policymakers will need to reverse years-long disinvestment in public education. Inflation-adjusted spending for Michigan schools declined for 15 years following 2002, which coincides with falling educator salaries, the report notes.

“Recent increases in state funding, if sustained and strengthened, should slowly begin to diminish turnover in Michigan’s rural areas.”

Increasing salaries, improving mentorship, creating greater flexibility in certification categories and requirements, expanding Grow-Your-Own programs to include high school students and other promising community members, and building upon recent historic new recruiting programs—all are promising potential initiatives for reducing shortages noted in the study.

Similar factors complicate efforts to address students’ mental health. While the last two state budgets have included significant funding increases for hiring mental health personnel in schools, shortages of counselors, psychologists and social workers already existed – and are compounded in rural areas.

Superintendents interviewed for the study say short-handed educators are experiencing serious – often dangerous – classroom behaviors which are especially exhausting amid the stress of the pandemic and another driver of the teacher shortage.

One superintendent characterized the situation: “Students are coming [to school], I would say, with far fewer coping abilities, carrying family issues from home with them. We see more signs of depression, suicidal behaviors, lack of ability to form relationships, lack of ability to focus on learning and instruction, non-compliance behavior, or refusal to work.”

Two factors are pushing the mental health issue to crisis proportions – increasingly traumatic circumstances in students’ home lives and scarcity or absence of professional mental health services in rural regions.

State expansion of support for an innovative program at University of Michigan – known as TRAILS to Wellness – is providing training to school districts statewide to be able to deliver multi-tiered support for student education, intervention and risk management.

Other state initiatives to build the professional talent pipeline are promising but not fully implemented. Meanwhile, the report centers discussion on possibilities, barriers and pathways to establishing School-Based Health Centers (SBHCs), which bring a variety of services to students at school.

“Only two of the rural districts we studied had SBHCs. In both cases, superintendents noted how important they were in providing needed supports for their students.”

Another major problem area discussed in the report – broadband access – could be bridged in part by coming technological advances. But more must be done to coordinate between local, state and federal governments, service providers, and non-profit sectors, the study found.

Public and public-private partnerships or cooperatives could be used to address market failures and create economies of scale that reduce costs to the consumer. Schools could become hubs for building digital literacy and training students in IT support.

Improved broadband access, in turn, could support efforts to provide mental health services and expanded educational programming that otherwise would not be available to rural and isolated districts – all of which would position rural communities for healthy development, the study found.

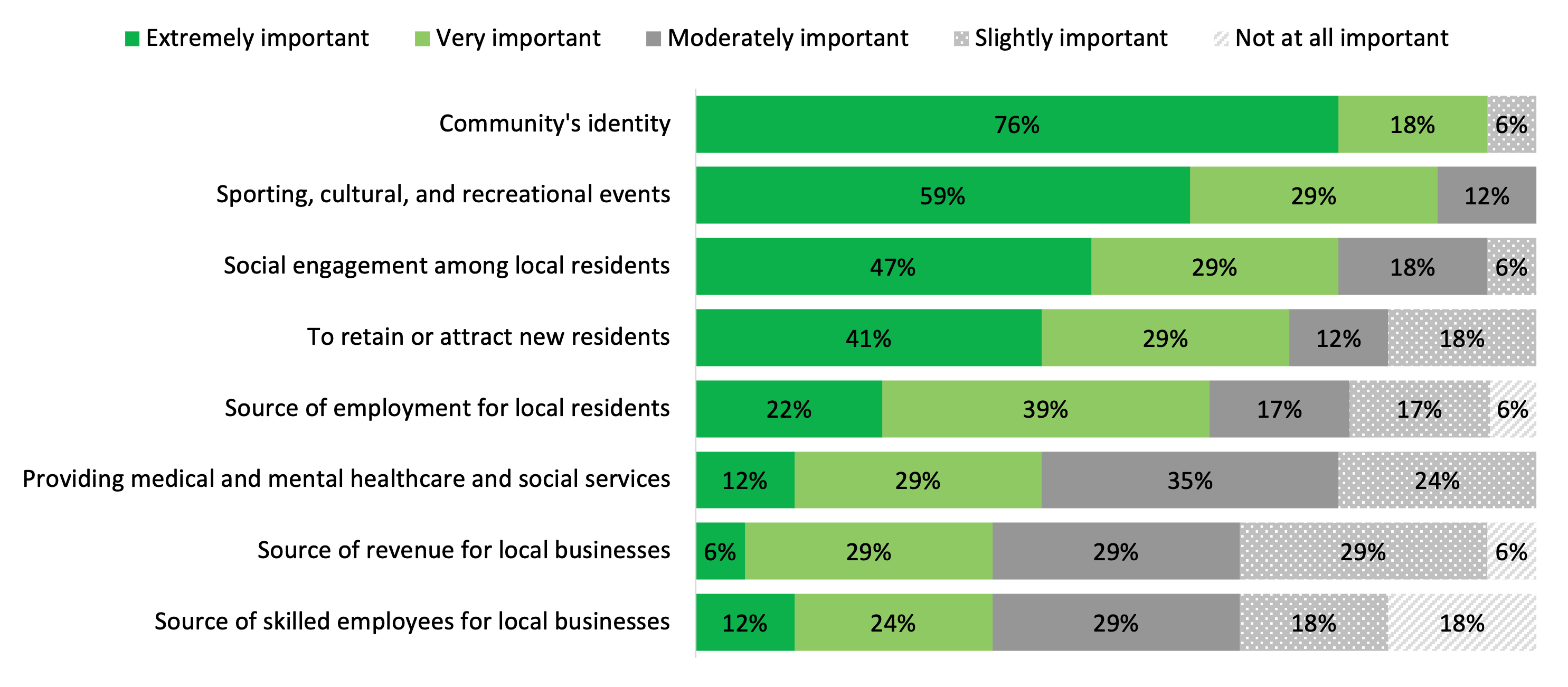

Even more so than in urban and suburban regions, the school district is typically the community center in a rural area – a gathering place, employer and resource hub all in one.

“Michigan is blessed with extensive rural areas characterized by striking natural beauty — lakes, trees, hills — and quaint towns. All Michigan rural communities need to spur sustained growth is good schools and good broadband access,” said Arsen, the lead author, in a news release.

Instead, Michigan’s rural areas lag in job growth, are losing population, and as a whole are older and poorer than non-rural areas. With less access to health care, rural life expectancy has declined sharply.

“Children raised in Detroit and other Michigan central cities have very low chances of achieving upward mobility, and the same is true for children in many rural areas,” Arsen said.

Counteracting these forces will require bringing fresh thinking to long-standing problems, beginning with broadening our sense of the purpose of schools, according to the report.

“We rely on schools to develop students’ social skills and work ethic, to teach citizenship and civic values, to promote students’ physical and behavioral health, to prepare them for skilled work, and to expose them to literature and the arts.

“We should recognize the failures and collateral damage of our recent policy obsession with test scores and return to this broader definition of schooling.”

Many rural school leaders from the study reported they would like to offer more and better Career and Technical Education (CTE) for students, while at the same time business leaders are decrying skilled labor shortages in the state.

The report discusses strategies to create CTE efficiencies across rural regions and develop community-building programs, such as registered apprenticeships which prepare students to succeed in well-paying jobs that await them upon completion.

The report does not offer definitive recommendations but instead is meant to spark dialogue about how to replace one-size-fits-all state policies with place-based, rural-conscious options with broad potential for big payoffs to the state.

“In research and policy circles, we are accustomed to thinking about how communities (e.g. families’ socioeconomic status) affect schools. But we also need to be much more mindful of how schools affect communities,” the report said.

“Integrated efforts to advance educational opportunities in Michigan’s schools will spur needed development in the state’s rural communities.”