Reading, Writing, Literacy Leaders Raise Alarm over Book Bans

Part 4 of our 5-part “Freedom to Read” series

By Brenda Ortega, MEA Voice Editor

Michigan Education Association

MEA member Troy Hicks has always been aware of the dangers of censorship as a professor of English and education at Central Michigan University. But he remembers when his thoughts grew into concerns this year.

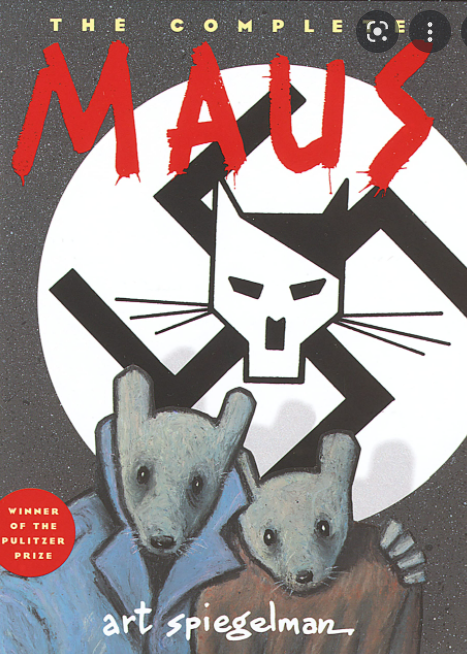

A troubling rise in book challenges was making national news as 2022 began. Then in February Hicks heard a local school board in Tennessee voted to ban Art Spiegelman’s acclaimed graphic novel Maus, which had been an anchor text in a Holocaust unit as part of the eighth-grade curriculum.

Published in 1986, Maus tells the story of Spiegelman’s parents’ imprisonment in Auschwitz – depicting Jews as mice, Germans as cats, and Poles as pigs. It became the first graphic novel to win a Pulitzer Prize and is widely hailed as a masterpiece.

The Wall Street Journal called it “the most affecting and successful narrative ever done about the Holocaust.” The McKinn County School Board banned Maus from the curriculum for use of swear words and depictions of nudity in the drawings of mice.

“That was definitely the moment where I said, OK, I’ve got to try to do something,” said Hicks, who also directs the Chippewa River Writing Project, a CMU site of the National Writing Project, a summer writing institute for teachers.

Attempts to ban books have dramatically increased across the country over the past year to the highest levels marked by the American Library Association (ALA) since record keeping began in the 1990s. Most of the targeted books feature content related to race, gender and social justice.

Attempts to ban books have dramatically increased across the country over the past year to the highest levels marked by the American Library Association (ALA) since record keeping began in the 1990s. Most of the targeted books feature content related to race, gender and social justice.

In Michigan, among dozens of titles sought for removal from school library shelves: The Bluest Eye by Toni Morrison, Half of a Yellow Sun by Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie, All Boys Aren’t Blue by George M. Johnson, and Stamped: Racism, Anti-Racism and You by Jason Reynolds and Ibram X. Kendi.

Hicks decided to put his skills to use in a couple of ways.

First he co-facilitated a session at the Michigan Reading Association’s (MRA) annual conference in March, “Standing Up and Pushing Back: A Conversation Around Book Bans and Censorship,” aimed at exploring what is happening and gathering resources in a crowd-sourced Google doc.

And from that dialogue came the idea to produce a joint position statement from the MRA, the Michigan Association for Media in Education (MAME), and the Michigan Council of Teachers of English (MCTE).

Along with three colleagues, Hicks co-produced the three-page statement outlining the rights and principles underlying the ALA’s fundamental belief to which their organizations also ascribe: “The freedom to read is essential to our democracy.”

Book challenges are not new, though the reasons behind them may shift, the statement notes: “today we see how those who wish to ban books still fear ‘obscenity,’ and also fear that their own children may feel ‘guilt’ or ‘shame’ about themselves.

“No matter the reason, these challenges persist and need to be addressed in a direct, clear, and swift manner.”

The statement underscores the need for school districts to have policies and procedures for responding to book challenges, for students to have a voice in decisions, and for books to be removed “only if absolutely necessary.”

It affirms the rights of students to read, of parents and caregivers to guide their students’ choices, and of teachers, librarians, administrators and school board members to offer books inclusive of the diversity found nationwide.

In that spirit of partnership, the statement concludes, “we stand firm in our belief that choice reading leads to stronger readers, critical thinkers, lifelong learners, and empathetic citizens essential to our democracy.”

Finally Hicks co-wrote an article for the spring issue of the Michigan Reading Journal – the publication of the MRA he co-edits – detailing the growing threat of book bans, the joint statement by the three organizations, and the crowd-sourced list of resources for responding to challenges.

The issue concerns Hicks as both a parent and educator. Caregivers absolutely have a right to make choices for their own students, but not for all, he said: “The right to free speech as well as the right to access all kinds of educational materials is essential to civic participation, democracy, and intellectual pursuit.”

With many state and national professional organizations joining together to lift up arguments against book banning, Hicks hopes to encourage civil dialogue going forward. In many places, school and library board meetings have devolved into shouting and name-calling.

“That is the larger conversation we need to have: How do we discuss important issues related to our democracy, while doing so in a respectful, courteous manner, where we may not ultimately agree but we can come to understand one another’s perspectives?”

MEA member Kathy Lester, a certified media specialist in Plymouth-Canton schools who is advocacy co-chair at MAME and incoming president of the American Association of School Librarians, said she worked on the statement with Hicks so librarians and educators know they’re not alone when facing challenges and angry rhetoric at school board meetings.

“The book challenges seem to be led by strongly organized and vocal groups,” Lester said. “Many surveys show that the majority of parents do not support book banning, so we need to come together and speak up in support of our students’ rights to read.”

Above all Lester remains concerned about students affected by the loss of access to books they wish to read. “The recently challenged books all have authors and/or characters from marginalized groups, and I want to stand firm in supporting our students’ First Amendment rights,” she said.

“I want to make sure that all students have access to diverse literature not only to see themselves but to see others in order to build empathy skills.”

One of the authors whose books are under threat in Michigan, Jason Reynolds, is an award-winning novelist for young adult readers now serving as the Library of Congress’ National Ambassador for Young People’s Literature. He is also working hard to call attention to the issue.

Reynolds has two books on the ALA’s top 10 Most Challenged Books list, both of which are critically acclaimed bestsellers centered on Black experience in America. He abhors the message that book bans send to young people—that there are things kids shouldn’t ask about, he says.

“The one thing [young people] hear every day is that there’s no such thing as a stupid question,” he told KidsPost, a section of The Washington Post written for young people. “The reason we tell people this is we want them to engage . . . with their own curiosity.

“It doesn’t mean that everything in these books has to be agreed upon. But your question deserves to live in the world.”

For all of those reasons, the Michigan Library Association (MLA) earlier this month launched a coalition-building effort known as MI Right to Read, which drew 250 sign-ups within a few days of its announcement, said Debbie Mikula, MLA executive director.

As soon as the coalition’s website went live, five requests for support quickly came in from libraries around the state, including a school district where protesters are demanding removal of 200 books based off of a list circulating on the internet.

The goal of MI Right to Read is to bring together people who wish to be allies in the effort to protect books from censorship with information and opportunities to get involved.

“We have to have language to talk about why all types of books belong in our libraries, and we need people in those communities to help send that message,” Mikula said. “It’s hard to be a librarian in these situations without having others that are going to stand next to you.”

COMING WEDNESDAY > Watch for part five in our Freedom to Read series: “Freedom to Read Advocates, Please Stand Up: ‘We need positive voices in the conversation’”