Educator-to-be: ‘We need minority teachers’

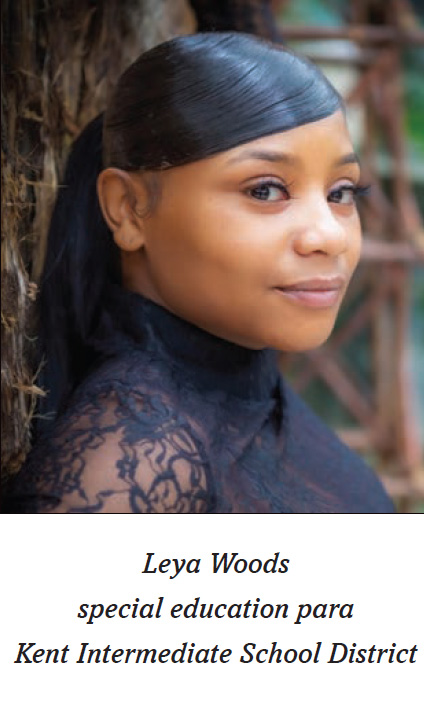

MEA member Leya Woods is concerned about the lack of teachers and administrators who come from minority populations across many school districts in Michigan and the message it sends to students of color sitting in all of those classrooms.

MEA member Leya Woods is concerned about the lack of teachers and administrators who come from minority populations across many school districts in Michigan and the message it sends to students of color sitting in all of those classrooms.

The problem is especially striking when comparing the number of support staff who are people of color working in lesser-paid roles – as she does – to the disproportionately low numbers in better-paid classroom and school leader positions with more authority, she says.

“Being a minority myself, I feel that students need to see more people who look like us in those jobs – who come from the same areas that we do and can relate to us – to see it can be done. We can achieve that.”

The 26-year-old is bucking the trend in a way that spotlights the potential of so-called Grow Your Own programs and scholarships that create pathways for Education Support Professionals (ESP) to transition into certificated roles such as teaching, counseling and social work.

Woods is one of thousands of educators who participated in MEA’s recent educator survey, which documented widespread concerns over the state’s critical educator shortage.

While working full-time over the last four years as a special education para at Kent Intermediate School District, Woods has made it two years into pursuit of a Master’s degree in Teaching in Special Education with an endorsement in Autism Spectrum Disorder through an online program at Eastern Michigan University.

“Now I’m realizing how expensive it is to get a master’s and a teaching certificate, and at times I’m like, Wow – I don’t even know if this will be worth it. Teachers don’t get paid well to be able to pay back loans like that.”

Despite the challenges of working and attending school full-time, Woods plans to persevere—especially since she recently became a mother when her son was born in March. “It’s motivation to get done so that I can better myself professionally and achieve more things in my life.”

Woods earned her bachelor’s degree in psychology at University of Michigan in 2017 not knowing exactly what kind of work she would pursue in the future. After graduation she enjoyed working with youngsters with special needs in a young 5s classroom at a charter school.

When she switched to Grand Rapids Public Schools and then Kent ISD, Woods found her niche in special education for adults. She works as a para with students who have emotional impairments and autism.

“I just love the job, being able to have an impact on their life. Getting to know them and relate to their problems. Eventually I knew this is the job for me—this is what I want to get my master’s in. So starting at this job – being in this job – helped me to see things clearly.”

A disciplined and strong student, Woods attended Creston High School in Grand Rapids – a majority Black school that had no Black teachers when she graduated in 2013, two years before the 90-year-old historic building was shuttered in a cost-saving reorganization of the district.

She used scholarships to get through her four-year undergraduate degree at UM while keeping her student loan debt around $30,000. But more is racking up quickly. It explains why capable students she knew in high school turned away from teaching, she says.

“People in high school were saying, ‘I don’t want to be a teacher; I know I could do it, but they don’t get paid that much.’ So a lot of people go different routes.”

In addition to raising pay, she believes the state should restore pensions for educators. “That would draw people in and make it easier to retain people, so maybe we wouldn’t have such a shortage.”

Related Stories:

MEA Survey Points to Educator Concerns