Breaking the Silence

New programs help schools address mental health, suicide crisis

By Brenda Ortega

MEA Voice Editor

Right down to the buzz haircut, MEA member Keith Garrison looks every bit the part he plays at West Bloomfield High School.

A 25-year physical education and health teacher in the district, Garrison tries to list all of the sports he has coached, but then gives up: “I’ve been a football coach, wrestling coach, track with shot and disc, and—I’ve pretty much coached everything in my lifetime.”

Now he has taken on one of the most important assignments of his career, teaching a new freshman health curriculum that asks him to do the opposite of what comes naturally—be quiet at times and let ninth graders sit in discomfort without him giving advice or drawing conclusions.

“As a coach, you always want to direct, ‘This is how we do the play,’” he said. “That was the hardest part of doing this; I will not lie. It was the hardest thing to sit there and allow uncomfortable silence. But I’m telling you… It. Is. Incredible.”

Garrison is in the second year of teaching Prepare U, an experiential 15-lesson mental health curriculum adopted after the district tragically experienced four student suicides in four years.

West Bloomfield High School Principal Patrick Watson is a forceful advocate for the program and speaks bluntly about the need for school districts everywhere to address student mental health as a priority that is “literally a matter of life or death.”

“If you look at the suicide rates, the number of students who have anxiety or depression, it’s off the charts,” he said. “I consider this the most important work I’ve done in my 25 years in education.”

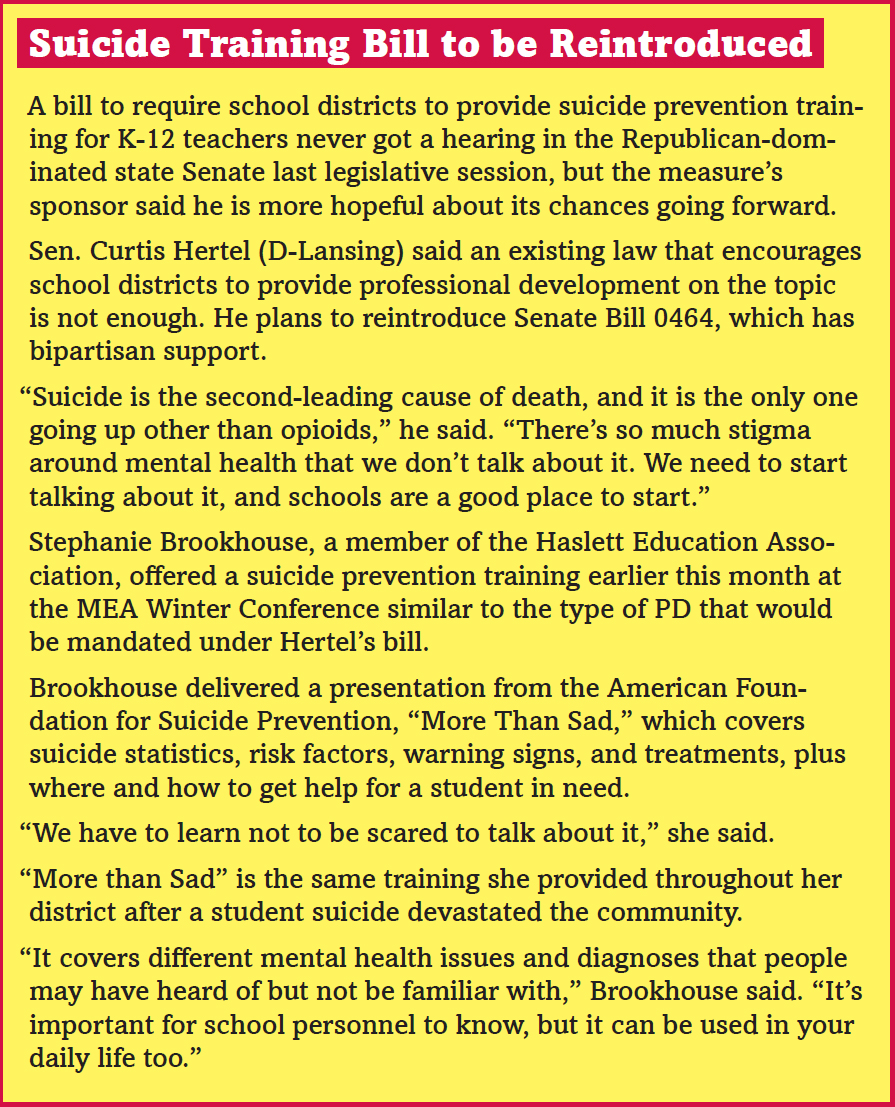

In Michigan, 217 people under the age of 25 died by suicide in 2017, compared to 122 deaths by suicide in the same age group one decade earlier.

Similarly across the U.S., suicide rates jumped 56 percent among children 10-17 between 2007 and 2016, according to the federal Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Suicide is now the second leading cause of death among young people 10-24.

“It’s a national crisis,” Watson said.

Prepare U is not a suicide prevention curriculum. Instead, it focuses on teaching students about mental health and mental illness, including suicide causes and prevention, in addition to giving kids tools to cope with common mental issues that affect most Americans at one time or another.

“As a society and culture we’re very good at understanding our neck down, but we’ve never been good at understanding the neck up,” said Ryan Beale, the founder of Prepare U, a licensed clinical psychotherapist and West Bloomfield High School alum who lost his older brother to suicide in 2009.

The multi-modal curriculum helps students understand mental and emotional risks ranging from suicide to family systems and grief, bullying, and social media use, and teens learn about and practice using evidence-based strategies for confronting and managing their own perceptions and behaviors, Beale said.

For more information, visit prepareu.live.

Now implemented in 23 schools in five states, Prepare U combines learning about mental and emotional health with facilitated group experiences in which students relate the content to their own lives with open conversations about difficult events and feelings.

No one is required to talk in group circles, and students begin by placing phones in a box and pledging confidentiality. “I’m a facilitator at that point and just kind of guide the way it goes,” Garrison said. “And what I’ve seen is a lot of kids get rid of a lot of baggage in that setting.”

A big goal for him is to build empathy among students at the school, so he focuses on it. “Kids need to get better at that skill on a day-to-day basis. We don’t know what everyone else is going through, but we can surely treat each other as if we do.”

He often shares the analogy that anytime a kid twists his ankle in gym class, people run to help. “But when a kid is sitting at lunch by himself, there’s nobody running up to him. When a kid is struggling in the hallway with his head down and clearly distraught, who goes up to him and says, ‘Are you all right?’”

Students say the class was “eye-opening.” Hearing others share experiences, reading anonymous essays from classmates about depression and anxiety, interviewing relatives about family history—all revealed that most people have difficulties they don’t show to the outside world, they said.

“It shows we’re not alone,” said sophomore Logan Lewis, who completed the class last year. “It’s not really a comfortable topic, but this class really showed me that I’m not the only one. Everybody goes through this.”

Sophomore Keyaira Wallace said she learned coping strategies—such as writing her thoughts to slow them down—and better understood the importance of talking and checking in with friends and family to make sure they’re OK.

“People come to school every day and put smiles on their faces, and you never know what they’re going through behind closed doors,” Wallace said.

Over the course of the 15 lessons, students learn, practice, and reflect on strategies for coping with anxiety, depression, and other mental health issues, using workbooks and journals they keep once the class is over. “It’s about filling their toolbox,” Garrison said.

West Bloomfield is hardly alone in seeking ways to help students cope with daily stressors and mental health issues and disorders.

Schools across the state report increasing need, especially escalating rates of anxiety and depression among students, at the same time that counselors, social workers, and psychologists have been dramatically scaled back from state education funding cuts over the past 10 years.

Michigan has the third highest student-to-counselor ratio in the nation at 729 to 1, far above the 250 to 1 ratio recommended by the American School Counselor Association. School psychologists and social workers are listed on the state’s Critical Shortage Disciplines again this year.

“The burden on them is tremendous,” said Dr. Elizabeth Koschmann, program director for the University of Michigan Depression Center’s TRAILS program (Transforming Research Into Action to Improve the Lives of Students).

In late January, Rep. Leslie Love (D-Oak Park) introduced House Bill 4054 to require public schools to employ at least one counselor for every 450 students. The bill has 27 legislators who signed on as co-sponsors.

“I think that no one would be surprised to learn that school social workers, counselors, psychologists, nurses, specialized teachers—not to mention instructional staff—are experiencing huge rates of burnout,” she said.

To help fill the gap, Koschmann’s TRAILS program has been building a statewide system of coaches who will train school staff in strategies that have been shown to reduce symptoms of anxiety and depression, including Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) and mindfulness.

The TRAILS program focuses on teaching evidence-based skills and practices, appropriate for every student, to slow down teenagers’ impulsivity, Koschmann said.

“If we look at what causes suicide and what causes homicide and what causes behavior that results in a disciplinary action among students, it’s impulsivity,” she said. “It is the inability to take something that’s hard in the moment and pause before reacting.”

Through TRAILS students learn about a pattern that drives human reactions, starting with a situation which causes thoughts, which trigger feelings, which lead to behaviors. For a teen with depression or anxiety, who hasn’t learned awareness of that pattern or strategies to slow it down, the behavioral consequences can be dire, Koschmann said.

With grants from the National Institutes of Health, local foundations, and Michigan Medicaid, TRAILS has trained community mental health professionals in 66 of 83 Michigan counties over the past two years to work directly with school personnel in area school districts.

For more information about TRAILS and to view the program’s CBT and mindfulness curriculum for at-risk student skills groups, visit trailstowellness.org.

One of the districts benefiting from TRAILS is Chelsea Community Schools. Like so many others, the community has been deeply affected by recent student suicides—two in the summer of 2016 and a third in the winter of 2018.

“We started seeing an increasing number of students struggling with anxiety, depression, and self-injurious behaviors about five years ago, prior to the three student suicides,” said MEA member Ellen Kent, school psychologist at Chelsea High School.

“It appears that what we were seeing in our school followed state and national trends, which is little comfort when you are working with students who are in pain and need help.”

The district has launched several initiatives to provide more support for students, Kent said, including implementing a mindfulness curriculum for all freshmen as part of their required fitness and health class.

The school’s most at-risk teens can participate in a Dialectical Behavior Therapy group that runs year-round, and a successful millage increased the number of school counselors, social workers, and psychologists in the district.

In addition, the high school was selected last spring to be part of the TRAILS program which offered training and ongoing direct mentoring for staff to deliver CBT and mindfulness education to students through eight-week group sessions and one-on-one interactions.

“This work can be heartbreaking, exhausting, and is never-ending,” Kent said. “But without a doubt, our students are worth it.”

One in five school-age children will be impacted by mental illness, but only 20 percent will receive help and of those, 8 in 10 will receive services only at school.

School mental health advocates have long pushed for additional resources in Michigan, so many cheered in December when Gov. Rick Snyder signed a supplemental spending bill to add more than $30 million for school mental health services.

The money will be designated for hiring additional mental health care providers in existing School-Based Health Centers and for intermediate school districts (ISDs) across the state to work with local schools to provide mental health services.

For West Bloomfield’s Garrison, it’s important to keep shining a spotlight on the issue and to keep asking the question—what more can be done?

In just three semesters, the burly football coach has already stepped out of his comfort zone to move 700 freshmen through the Prepare U curriculum—and sparked new fire in his teaching. He’s shown students how to be vulnerable and been willing to scrape off a bit of his shiny teacher veneer in the process, he said.

He’s celebrated when students sat in uncomfortable silence, grappling with a difficult question, until a ripple of talk became a wave of honest conversation. He’s been grateful to see kids more willing to approach him with problems they’re experiencing.

And he’s marveled at the “breakthrough” moments when kids suddenly realize they’re not alone in having troubles that they never knew their classmates were struggling with too.

“Holy mackerel, it’s like scoring the game-winning touchdown,” he said.

[dt_divider style=”thick” /]

RELATED STORIES:

Above and Beyond – An MEA member in Brighton has spent 10 years developing a first-in-the-nation program to bring service dogs to every building in the district, helping to address students’ social-emotional needs. What’s more, the program is completely funded by the community.

Members Bring Mindfulness to Schools – MEA members are in the vanguard of a movement that is bringing a practice known as mindfulness to schools across Michigan and the U.S. More than a fun extra, mindfulness initiatives aim to help address growing concerns about youth mental health as teen suicide rates are increasing and studies show more than one-third of American young people suffer from anxiety.