New Standards Transform Science Instruction

By Brenda Ortega

MEA Voice Editor

MEA member Holly Hereau teaches science in a suburban Detroit setting, but she grew up in the wild.

The 15-year veteran of South Redford School District fondly recalls a childhood in the Upper Peninsula’s Escanaba area playing outside with her friends—mostly in the woods, discovering nature by following her curiosity wherever it took her.

“Nobody had a cell phone back then; we’d be exploring and checking stuff out and always asking questions,” Hereau says. “I think that’s what spurred me on to be a biologist in the first place.”

Hereau was studying entomology in graduate school at Michigan State University when she first became interested in teaching—drawn in by her work as a teaching assistant doing hands-on project-based learning with undergraduate students.

But her early experience teaching at Thurston High School was disappointing. She found herself delivering the same content in the same way every year. The kids who were good at memorizing facts got good grades but were bored. The kids who weren’t good at memorizing hated class.

“And nobody was good at figuring anything out,” she said.

That has all changed.

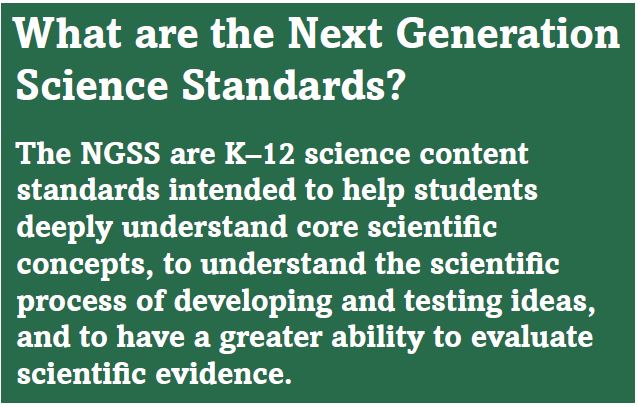

Several years ago, Hereau began following her curiosity about a new approach to teaching science, which eventually became known as the Next Generation Science Standards (NGSS). Today every K-12 science teacher in Michigan is required to follow suit.

Many educators across the state have been test driving NGSS for three years since the Michigan Board of Education adopted them as the Michigan Science Standards in late 2015. Next spring the rubber hits the road: students will take NGSS-aligned standardized science tests in grades 5, 8, and 11 for public release.

Developed by scientists and educators from across the country over several years, the NGSS grew out of frustration that science standards and curricula nationwide focused too narrowly on facts and recall, instead of exploration, discovery, and problem-solving—the cornerstones of science and engineering.

Developed by scientists and educators from across the country over several years, the NGSS grew out of frustration that science standards and curricula nationwide focused too narrowly on facts and recall, instead of exploration, discovery, and problem-solving—the cornerstones of science and engineering.

Now adopted by 20 states, the standards represent a dramatic paradigm shift. Instead of learning about scientific topics, students are asked to use scientific thinking and practices to figure out natural phenomena that are not easily explained.

“So they’re asking questions and getting ideas of investigations that could answer those questions, and then they put all the pieces together to explain it at the end,” Hereau said.

Everyone agrees the change is important for improving scientific literacy in the U.S. and attracting more students into STEM-related studies and careers, but it’s described as complex and time-consuming for educators. For Hereau, it’s also exciting.

“This shift has really made me excited to teach again,” she said. “It’s so much fun, because it gets the kids to think. I spend my time asking questions and discussing instead of telling them stuff they need to memorize.”

Hereau is spreading the love. As an early adopter who attended lots of professional development, she has become an expert on the new standards, training teachers at conferences in Michigan and across the U.S. in addition to writing and reviewing open-source curriculum and assessments.

Last December, Hereau was named the 2019 high school Michigan Science Teacher of the Year.

“Prior to the release of the NGSS, I was pretty overworked, burnt out and ready for a career shift,” she said after receiving the honor. “I’m still overworked, but seeing the progress my students are making has given me a second wind.”

The NGSS call for a “three-dimensional” approach to K-12 science instruction that marries content and process.

Those three dimensions weave together core ideas specific to each scientific discipline (life, physical, earth and space, engineering and technology) with scientific and engineering practices (investigation into answers, designing solutions and constructing model-based explanations) and crosscutting concepts that are common to all areas of science (cause and effect, stability and change, etc.).

Vicksburg High School science teacher Liz Ratashak agrees the standards are strong, but making the change requires training, time, and work.

“In my experience, people are excited about it because it feels really authentic,” the 28-year veteran said. “We’re in the business of educating people, so when we see a way that works, it’s exciting even if it’s difficult.”

Ratashak served as lead teacher in a three-year MEA collaboration with a Michigan State University project called Carbon TIME (Transformations in Matter and Energy). Funded with a grant from the National Science Foundation, the program provided MEA-member middle and high school biology teachers with six NGSS-aligned teaching units.

Two cohorts of MEA-member teachers (including Holly Hereau) received training at MEA headquarters, went back to their schools and field tested at least three of the Carbon TIME units, provided feedback to MSU, and acted as a resource to other educators in their school district and region.

“Anybody who’s going to survive in this job needs to work together and not try to do it alone,” Ratashak said. “If people in your district aren’t there to help, join MSTA, Michigan Science Teachers Association. Go to conferences. Seek it out yourself.”

Now MEA and the Ann Arbor Education Association, working cooperatively with the school district administration, have helped to bring the Carbon TIME training to members’ doorsteps.

Science teachers in Ann Arbor are participating in local professional development workshops and other forms of ongoing support that will connect educators together in helpful professional learning networks going forward.

More locals are expected to launch similar initiatives in coming months.

Educators need coherent and continuous professional development on the standards, because the learning goals and classroom practice expectations are much more ambitious than in the past, said Christie Morrison Thomas, the MEA Carbon TIME network leader and an MSU graduate student in Curriculum, Instruction, and Teacher Education.

“The kind of classroom discourse that’s required for students to be figuring out a natural phenomenon instead of learning about scientific topics is hugely different than teachers generally have practiced before,” Morrison Thomas said. “It’s required a lot of time and experiences with colleagues and professional learning experts in a planned course of study—not just one or two days in a workshop.”

Educators across Michigan are at widely varying stages of progress in making the switch to the new standards, with some still at a beginning phase and others farther along the path.

Carbon TIME is available for free online at carbontime.bscs.org. More and more freely accessible material is coming available as time passes—much of it the result of grant-funded collaborations between university researchers and educators in the field.

The hope is that school district administrators who understand the magnitude of the change in standards will redirect money from buying textbooks to supplying teachers with quality professional development.

One virtual resource for exploring the standards—stemteachingtools.org—also includes open-source professional development modules for educators and clear but distilled “practice briefs” for learning more about opportunities and challenges of teaching the NGSS, according to Morrison Thomas.

A widely recommended curricular resource—Next Gen Science Storylines—is praised for its engaging approach at nextgenstorylines.org. A related full-year biology course curriculum (which Hereau contributed to) and middle school magnetism unit is also open source, including assessments, at colorado.edu/program/inquiryhub/.

Check out this list of high-quality NGSS teaching resources.

MEA member Beth Lehner was one of many elementary teachers in several west Michigan districts who piloted an NGSS-aligned open-source curriculum developed through a partnership between three universities, including University of Michigan and MSU, called Multiple Literacies in Project Based Learning.

“The kids are way more engaged and excited about science than ever before,” the third-grade teacher at Sparta’s Appleview Elementary School said.

However, as with many educators learning the new standards, Lehner found the time required to complete a unit is the biggest challenge. “We didn’t get to everything last year, because that time is split between science and social studies. The people that did finish all the science didn’t get to the social studies.”

Lehner liked that the curriculum targeted reading and writing skills along with the science. Students were reading to explore answers to their questions and writing summaries and reflections that made connections.

“It’s a lot less teacher-driven and a lot more hands-on with kids figuring things out and drawing conclusions,” she said. “It brings science alive and gives students the thought process of how to work through questions about a phenomenon.”

In Zeeland, middle school science teachers are using a curriculum developed at Michigan Technological University, known as Mi-STAR. MEA member Lara Minnear volunteered to be a lead teacher for the district and helped phase in implementation over three years in grades 6-8.

Educators wishing to use Mi‑STAR must complete professional development before getting access to the courses.

“Now that we’re in year three, we’re starting to see the benefit of having our students utilize these standards in the classroom,” Minnear said. “And we’re seeing our teaching come around to the point where we can understand how best to teach them. We see that our students are learning how to think about science rather than just the what of science.”

Mi-STAR is not a perfect resource, but few things are, the Creekside Middle School seventh-grade teacher said. “What we’ve loved about working with the people at Michigan Tech is they are continually looking for teacher feedback and then revising and tweaking the units.”

The NGSS represent a major change in practice for every science teacher in the state, she said. The lessons and units are time-consuming. Not as much content is covered, which can be hard for educators, she added.

But the benefit is that students get to explore their own curiosity and understand the application of what they’re learning.

“I have seen students making more real-world connections than I’ve ever seen before with them being able to see, OK, we’re learning science concepts in class but then this is how they’re used in the world,” Minnear said. “That has given real validity to what we do in class.”

What will NGSS-aligned assessments look like?

How to assess student learning is one of the challenges of making the shift to the Next Generation Science standards.

- The Next Generation Science Assessment (NGSA) group is a multi-institutional collaborative that is designing classroom-ready formative assessments for teachers to gain insights into their students’ progress on achieving the NGSS performance expectations at nextgenscience.org.

- The Michigan Department of Education released sample science assessment items to help teachers and students prepare for the science M-STEP test for grades 5, 8, and 11 at tinyurl.com/MISampleSci.