Teachers Describe Responses to Harrowing Attack: ‘This will not be what defines Oxford’

![]()

By Brenda Ortega, MEA Voice Editor

Michigan Education Association

MEA member Jake Trotter says he’s the type of person who likes having structure to his days teaching mostly upper-level world history classes and the second-year history course in the Diploma Programme (DP) at Oxford High School, an International Baccalaureate (IB) School.

Trotter’s sense of order was shattered on Nov. 30 when a student opened fire with a semiautomatic 9mm handgun in the hallway near his classroom at 12:51, shortly after the 15-year veteran finished lunch and one minute from the bell to start fifth hour.

Trotter was standing in the hallway, thinking about coaching his middle school boys basketball game that night, planning how he would get his school work done in the evening’s time crunch, and greeting students entering his room as he tries to do with every one every day.

“From the right, down around the corner, I heard the first five to seven pops,” Trotter said. “Out of the left corner of my eye, down the other end of the hallway, I see kids just sprinting. There’s a girl walking near my doorway to my right as this happens, and I take my right hand and just stop her. I literally grab her sweater and throw her into my room. I think I almost ripped her sweater.”

Harrowing stories of confusion, terror, heroism and sorrow emerged in MEA Voice interviews with several Oxford teachers and the local union president in the weeks since the deadly attack killed four students and injured seven, including a teacher.

Like all of those interviewed, Trotter followed protocols from school-wide ALICE training by pulling students into his room, directing them to take cover in a corner out of view, then quickly closing his door and securing it from outside entry by engaging the Nightlock security door stopper the district installed throughout the building four years ago.

Ever since the horrific events of that day, Trotter has suffered effects that are common after a major trauma: difficulty concentrating, lack of motivation, grief and depression. For three weeks, he felt “physically awful,” he said. “I think the physical aspects were the hardest on me. I didn’t sleep well. I’m still not sleeping great, but we’re getting back to it.”

Six weeks after the tragedy, students and teachers came together again for the first time in a school setting. At first they shared the middle school, alternating days in the building and remote learning. They returned two weeks later to the refurbished high school with 91% of students in attendance.

When they first arrived at the renovated high school building on Jan. 24, students were greeted with new carpet, paint, wall graphics, and notes of love and encouragement from their elementary and middle school counterparts, written on paper hearts and snowflakes that were taped to lockers.

Trotter had expected one of the toughest days would be the first half-day back at the middle school. In days leading up, he felt both excited and nervous to meet with his tight-knit DP history class, a cohort of 20 students who’d been together for years in classes that lead to college credit.

One student would be missing from the group, Justin Shilling, 17, who died one day later from injuries sustained in the attack. Dozens of students, parents, and community members had gathered outside of the hospital where Justin was treated to be part of a traditional “honor walk” before his organs were donated to save others.

“There are no words for the feeling you have as a teacher to lose a student in this way, more so when you just saw him earlier that day and you remember the conversations you had with him, and he was just the nicest kid with the best sense of humor.”

In the early days of December, immediately after the rampage, hundreds more people gathered at separate funeral services to mourn Justin and three others who died, Hana St. Juliana, 14, Tate Myre, 16, and Madisyn Baldwin, 17.

The first half-day back at school was more joyful than expected, Trotter said. For that he credited extra time over an extended holiday break to grieve, gather informally, and process events; plus thoughtful preparation by the school district, including bringing in Dr. James Henry from the Western Michigan University (WMU) Children’s Trauma Assessment Center to work with both staff and students.

Despite Trotter’s nerves, along with sadness that day, “there was laughter and smiles and kids reconnecting,” he said.

‘We have each other’

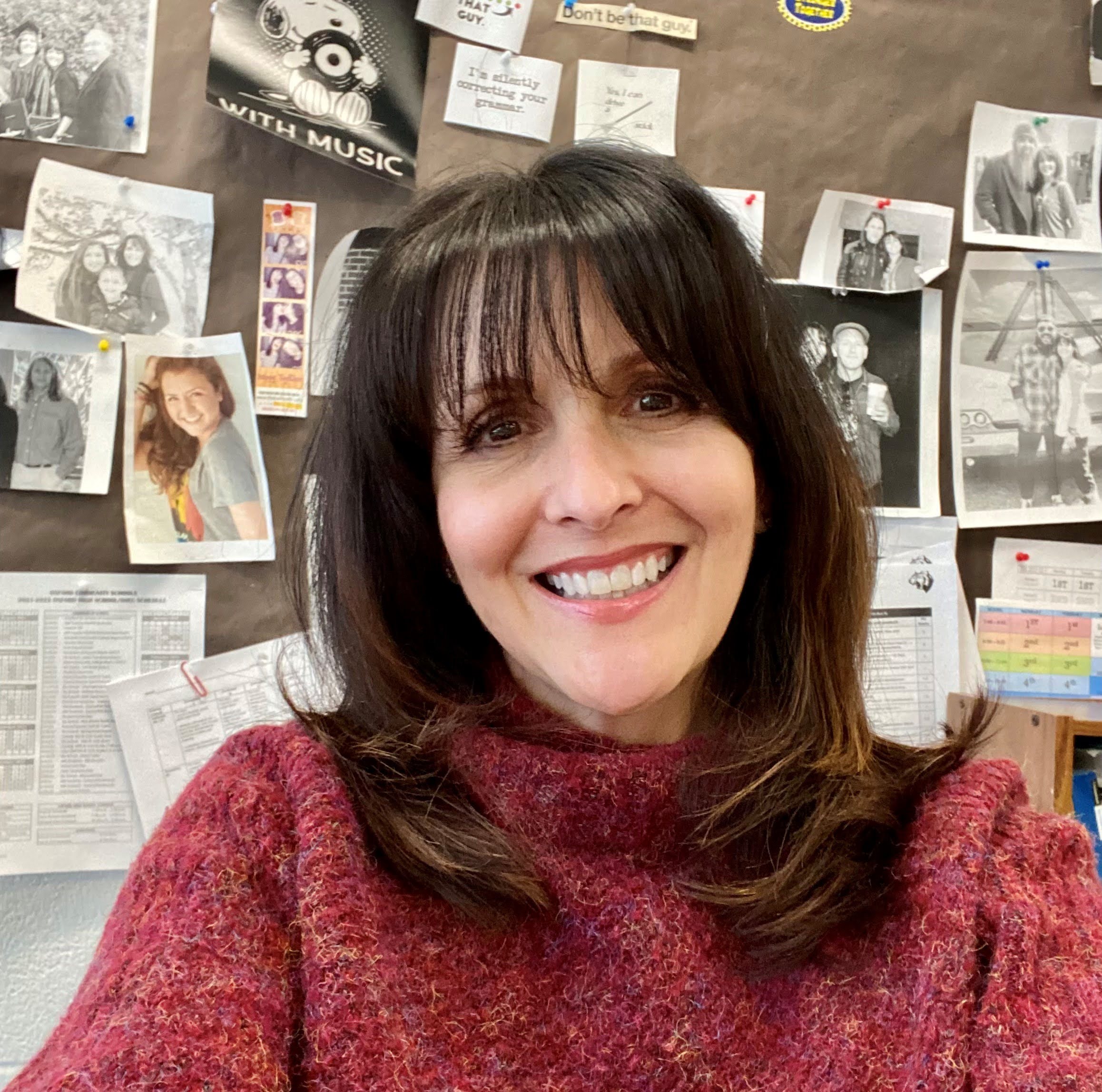

Language arts teacher Gina Sambuchi-Black agreed. Everyone was nervous going back, and she wondered if she would say the right things. As a 30-year educator, she knew how to pivot when a lesson didn’t go as planned, but in this case each person was experiencing effects from the trauma in different ways.

Sambuchi-Black decided to share her own vulnerability with students because she knows they value honesty. She talked about one day when she was headed to a faculty meeting with Dr. Henry from WMU and forgot where she had just been driving for several minutes.

“I explained about disjointed thinking, because I wanted them to know in a very real way—yes, I’m this adult, but I’m going through things. You’re going through things. And there’s not a script or a game plan or a right and wrong way to do it. There’s going to be good and bad days, but ultimately the fact that we have each other is going to be one of the best things.”

In discussions, she asked students to cite one word to describe their feelings about returning to school, and the most frequent word chosen was “relieved. The kids were happy to see each other and really happy to see us,” she said. “A lot of kids said to me, ‘I need to be back with people who understand me, who went through this with me. Everybody else means well, but they weren’t there; they don’t know.’

“It’s almost like this cohesive group of people who are all hurt in so many different ways, yet there’s some kind of commonality in that,” Sambuchi-Black concluded.

A teacher in Oxford since 2001, she also had a student missing from one of her classes that first day back, Tate Myre, a star football player she called “a phenomenal kid, just beautiful” and “the kindest.”

“I think all of us (educators) have had to go to a funeral service for a kid—whether there had been an accident or illness—and it’s crushing because they’re so young and have so much promise,” she said. “But we never expect to attend a service because our kid was lost in a school shooting. Isn’t that something we watch on TV when it happens in other places?”

Living through the attack had an unreal quality because time moved slowly, Sambuchi-Black said. She’d been standing in her classroom doorway when she heard “the strangest sound, like a cacophony off of lockers, but I knew it wasn’t right, if that makes any sense.”

She remembered in the room across the hall, a substitute teacher was filling in. When some students ran past her, Sambuchi-Black heard one yell “Gun!” She shouted for the sub to lock down, pulled her own door closed, and secured the Nightlock.

For 50 minutes, waiting for a law enforcement signal that it was safe to come out, her students huddled wide-eyed in the corner, becoming more frightened and upset when they heard that a girl from their class who didn’t make it to the room had been shot in the neck.

“The kids were getting reports from their friends in other parts of the building in real time. I’m trying to keep them calm, saying ‘She’s going to be OK; we’re going to be OK.’ I mean, that’s what you do in the moment. And the kids were so amazingly supportive and loving to each other, holding hands, giving words of comfort to each other.”

‘I will never forget’

Students also displayed acts of bravery amid the chaos and destruction, according to sixth-year social studies teacher Joe Fedorinchik, an Oxford High School alum and junior varsity boys basketball coach who said every student in his room had eyes on him and followed directions without questioning.

“The resiliency I saw that day is something I will never forget,” he said.

Fedorinchik had just returned to his classroom from eating lunch with two fellow social studies teachers a few doors down when the attack started not far from the room where he’d just been. “I was walking toward my door, I believe going out to the hallway, when I heard pop-pop-pop-pop-pop.

“I believe a student right near my door was coming in and I grabbed him—it’s kind of fuzzy—but I think I pulled him in, slammed my door shut and grabbed my Nightlock.”

Fedorinchik and four boys barricaded the door with desks before joining others crouched in a corner. They heard all of the shots, he said. Five or six at at time, then a lull. Then five or six more. Time dragged as he crawled around to comfort a girl who was shaking and others who were quietly crying.

Most of the teachers, including Fedorinchik, identified a moment when the gravity of events broke through their shock. For him it came during lock down when he learned a student missing from his class had escaped the building and was driving a basketball player who had been shot to the hospital.

“That was the moment where it really set in that kids had been shot. I remember putting my head to the ground, and it was probably the one time where I kind of lost it for a brief moment.”

A student who had received a text about the news reassured Fedorinchik the injured student was OK. “He just had a lot of blood. The kid who drove him—who was supposed to be in my class—took his shirt off, wrapped it around his leg and drove him to the hospital.”

Later Fedorinchik would learn of a girl from a different class—someone he cares about deeply through close friendship with her family—who likely saved the life of another girl who was shot.

“She was in the initial hallway and somehow didn’t get shot but helped drag the injured student into an empty classroom, applied pressure to her wound, called her mother and prayed with her. This girl is all of maybe five-foot-one, 100 pounds.”

And a story of another basketball player who fled the building and was running to his car when he spotted a girl holding a wound in her neck and rushed her to a local clinic. “Just so many stories that are a testament to how awesome our kids are.”

Administrators in the building also risked their own safety to help others who were injured, even as bullets were still being fired nearby, he said. “Our admin literally ran into it. It’s truly amazing, and I’m so grateful for them.”

Later that day Fedorinchik and other family members gathered at his parents’ home where he grew up, including seven nieces and nephews who attend the high school and escaped injury. There his nieces learned of the death of their friend Hana, a freshman multi-sport athlete known for her kind heart.

Another victim, Madisyn, was an artist and senior who transferred to the school this year. Soon Tate’s death was also confirmed. As a longtime baseball umpire in the region, Fedorinchik has known Tate’s family for a long time but just got to know the junior well when he had him in class this year, he said.

“I can’t remember if I had talked with him the day it happened or the day before, but he was telling me about his (college) visit that he had just made to Toledo. There’s no doubt in my mind he would’ve played Division I football. He loved Michigan State, and I love Michigan State, so we talked about that quite a bit. His energy was contagious.”

Returning to that third hour was especially hard because several of Tate’s friends were also in the class, including his best friend. Fedorinchik addressed the loss directly.

“I wasn’t sure what would be the right thing to say, so I told them that. Then I talked about what type of kid he was and about the legacy he leaves and the impression he made on me and in the community. His friends were embracing each other while I was talking.

“Basically I wanted to make myself available and let any of these kids know I’m always available to you, whether it’s after school today, or whether it’s next week, next year or 10 years from now.”

‘This is what we do’

Like many in Oxford, language arts teacher Melissa Gibbons wears dual hats as both a parent and teacher in the district. In addition, husband Jim is the high school band director and local union president, “so this is what we do. We teach. We have our kids. We’re in the community. Pretty much our whole life revolves around Oxford and Oxford kids.”

That meant on the day of the shooting, she was simultaneously following lock down protocols and worrying about her senior twin daughters.

While Jim and the couple’s youngest daughter Sarah were out of the building that day, the couple’s twin daughters were located in a classroom at the epicenter of the shooting. Their teacher did not make it into the room, so the girls—Hannah and Emma—at first texted they weren’t locked down.

Melissa had directed her students to hide in the corner, and she forwarded her daughter’s text to the principal. Next she received another message saying a student had applied the Nightlock to their door. “Then I went back to trying to reassure my students,” she said.

Later a bullet hole would be discovered in the classroom where her daughters were hiding. But meanwhile, Melissa was keeping an eye on windows behind her desk, because the blinds weren’t drawn and she wanted to anticipate if the shooter would suddenly appear.

Eventually, when a knock came at the door identifying law enforcement, she crept forward to get an angle where she could look through the door’s window for a badge or uniform. Once she confirmed it was safe, she opened the door. The students began moving, and the deputies were calm, she said.

A student flagged her attention toward an autistic classmate who was curled up on the floor and not moving, “so I talked him through. I said, ‘They’re here to get us out safely. I need you to get up. It’s OK.’ And he did.”

It was a somber walk through a gauntlet of first responders directing movements. Students were told to leave backpacks and walk out with arms raised. Melissa heard from a friend who had picked up her daughters, so she made her way to the evacuation site, a Meijer store one mile from the school, where she connected with Jim.

A sense of shock would help her continue to function until she got home, saw her daughters were safe and watched news reports. Then the tears came.

‘Everyone is tight-knit’

Social studies teacher Al Poynter spent lockdown in the classroom next door to Melissa and Jim’s daughters. He and good friend Pat Crowe had spent lunch together with Fedorinchik and the two were standing in the hallway together as they often would, urging students, “Hey, yo, guys! Get to class!”

The one-minute reminder music had started to play, warning students of the impending tardy bell, and when the first shots rang out the shooter was so close that Crowe couldn’t get to his classroom. Following their training protocol, which says the first priority is to eliminate targets from the hallways as quickly as possible, they both took refuge in Poynter’s room.

Crowe put in the Nightlock door stopper. In his classroom next door, where the Gibbons’ daughters hid with others from his fifth-hour class, he would later learn a student engaged the security device. Poynter signaled for students to stay very quiet. Some cried silently with tears coming down their faces.

Every couple of minutes more shots sounded, closer than before. “We heard some shots maybe right outside our room or a room down,” Poynter said. A couple of times in the first five minutes, the doorknob jiggled and he believed it might have been the shooter.

“I give the students an A+ for doing such a fantastic job of staying calm,” Poynter said.

Crowe said it was unbelievable how quickly the lockdown happened and cleared the halls. In the weeks since the ordeal, an even more impressive outpouring of support from the Oxford community has helped to bring students and staff back into a sense of safety and connection, he said.

“Oxford is a huge school of 1,800 students, but it feels like a small community,” Crowe said. “Everyone is tight-knit and they really support Oxford schools.”

In every interview, teachers spoke of the importance of support and love they felt from business owners and residents in the community sharing food and donations and posting signs and blue-and-gold ribbons all over town.

In addition, the outpouring of love and concern was unreal from other MEA members and units across the state and people all over the country—including cards, messages of well wishes, and more than 500 packages sent from an Amazon wish list the music department posted for students, Jim Gibbons said.

“It’s going to be impossible for us to thank all of these people directly who reached out to us in such a difficult time, but it meant more than they will ever know,” the 18-year union president added.

Legacy 925, an indoor fun center became an especially meaningful community gathering place and safe space for students and staff in the weeks after the tragedy—mostly informally but school leaders also organized a fun event there with bus transportation for those who needed it.

“It was important to pull some joy back into the community,” Gibbons said.

The Oakland County Sheriff’s office provided immediate trauma counseling, and MEA offered several weeks of daily on-demand grief counseling for school employees, staffed by licensed clinicians at the field office in Lake Orion.

‘What makes all teachers heroic…’

Educators in Oxford don’t want to be hailed as heroes for protecting students they love, said Gina Sambuchi-Black, the longtime language arts teacher, but it would help for people to understand how many extra layers of work and expectation they have seen added to their jobs over the past two decades.

“What makes all teachers heroic is having these broad shoulders where more gets put on there, yet people are still willing to keep going,” Sambuchi-Black said.

She similarly described the community as having a culture of grit when it comes to tackling big challenges, and this one is no different. “The parents and the kids and the educators in this community are bound and determined,” she said. “This will not be what defines Oxford.”

You can send a message of support to educators in Oxford, and MEA will pass it along.

RELATED STORIES:

After Oxford: ‘Normal is not a thing right now’

God bless you for all that you do for the students in Oxford. Although I graduated from OHS in 1972 and moved from the area in 1976, Oxford continues to be home to family and holds a special place in my heart. As a retired educator, I know how special a school community can be and I know that Oxford can, and will, continue to move forward in their recovery. “Oxford Strong”

Thank God for all of you

This is such an important story to tell. The love and support is amazing. I live in Oxford and am an educator in a neighboring school district. I can say without a doubt this is every parent and educator’s worst, worst nightmare!

I agree with Gina S when she said, “ but it would help for people to understand how many extra layers of work and expectation they have seen added to their jobs over the past two decades.”

There is still so much to do to heal in this community. I want to continue to stress kindness and the phrase that I have seen posted so many times “love always wins”!