Union Caucus in Ann Arbor Targets Special Education Issues

Engagement * Bargaining * Advocacy * Justice * Empowerment * Support

by Brenda Ortega

MEA Voice Editor

Four years ago, MEA member Dr. Tracy Loveland joined with a fellow Ann Arbor school psychologist to bring the union’s strength to bear on frustrations within the district’s special education department, which were contributing to high staff turnover.

“We were struggling to have a voice,” Loveland said. “We didn’t know how to express our concerns or make changes or implement things differently. We were just kind of silently muddling through.”

The two school psychologists approached local union leaders, and a special education caucus of the Ann Arbor Education Association was born. But it was too late to save Loveland’s colleague, who quit shortly afterward.

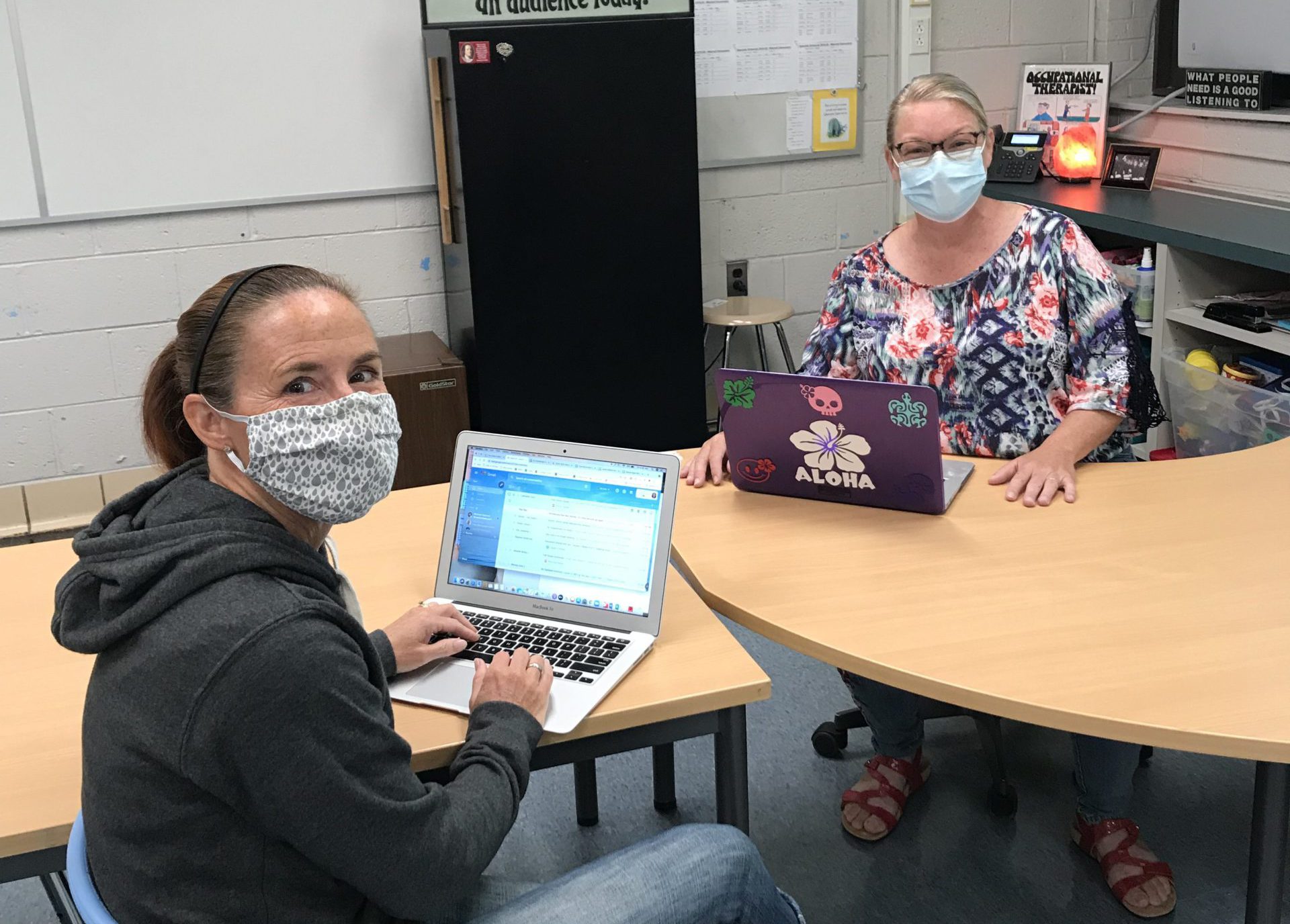

That was when Christy Yee, a 19-year occupational therapist (OT) in the district, got a phone call. “I worked with the other school psychologist, and she said, ‘I’m taking a different position—I can’t do this anymore. Would you take over as co-chair of the caucus?’ Of course I jumped on it, but we’ve lost a lot of really good staff.”

Issues that have plagued the special education department are not necessarily unique to Ann Arbor, says Yee, the district’s lead OT. Layers of bureaucracy governing services for students with disabilities—from the federal, state and district levels—challenge teaching and ancillary staff everywhere.

What is unique is the targeted approach to solving problems in Ann Arbor ever since the special ed caucus was made within the union, Yee said: “The benefits of what I can do and be and advocate for kids and for my services is just so much greater with having the union behind me.”

The caucus has helped to address high-priority problems in the department that contribute to dysfunction and employee dissatisfaction, including inconsistent procedures across district buildings, poor communication, lack of access to resources, and workload issues, Loveland and Yee said.

They are the kinds of struggles making the special educator shortage an even worse crisis than the overall educator shortage nationwide. According to the latest data from the U.S. Department of Education, 49 states and the District of Columbia are reporting special educator shortages.

The lack of candidates to fill special education openings affects 98 percent of school districts nationwide at a time when the population of children in need of services continues to grow, the Education Department data show.

“One thing that the leadership of the AAEA did was they started coming to our monthly meetings, and once they realized all of the stuff that was plaguing us they said, ‘Wow. We need a special ed person on the bargaining team,’” Yee said. “We never had that before, but it’s a necessary thing.

“As they’re learning what people’s lived realities are, it’s had an influence on our contract. To have a seat at the table is huge.”

Members of the caucus now meet monthly with the district’s executive director for special education with the opportunity for any member to submit questions via Google doc. In just three years that the caucus has operated, multiple administrators have moved through the role, and the turnover creates uncertainty.

“This gives us a way to respectfully push back when needed,” Loveland said. “We are the ground troops, so to speak, and we have experience that we can give voice to—whether it’s the issues affecting us or ideas for how to do things more effectively.”

The caucus has been so successful that another was inspired to form, said AAEA President Fred Klein. This year a new caucus of special area teachers is similarly engaging its members within the union to lift their voices and concerns with district leaders.

“Special area” includes music, physical education, art, and library/media at the elementary level and those subjects plus other electives at the secondary level. Like their special education counterparts, special area teachers have unique concerns that sometimes get lost within the larger union of educators.

“We think it’s a really good model that can help resolve more issues that members are having specific to their discipline,” Klein said. “Because these people are more informed, they get the speaking parts when it’s time to speak up. The great thing for me, as president, is it has taken some of the workload off of me.”

Made up of 24 occupational therapists, 13 school psychologists, more than 60 speech and language pathologists, several nurses, plus resource room teachers, self-contained teachers and teacher consultants, the special education caucus has claimed several successes in its first few years.

For one, Klein noted, the caucus succeeded in creating “district leads” among various Non-Certificated Professional Staff (NCPS) roles—which are the non-teaching professional staff in the department—and those new positions include stipends.

“Also, at one time the nurses had some issues that were unique to nurses, so they sort of subcommitteed that through the caucus and got a place at the negotiating table to resolve some of those issues,” Klein said. “It’s just been very well-executed and successful.”

Some protocols have been established to improve communication and clarify procedures and expectations for special educators, Loveland and Yee said. The improved clarity has also helped to reduce tensions between special education and general education staff, because people know where to direct questions.

Communication has similarly been improved with parents now that a caucus representative attends meetings between administration and a parent advocacy group to ensure everyone gets the same information at the same time.

Problems had been occurring with administrative information being shared with parents ahead of staff, so members would be blindsided by questions or comments from community members about situations or changes they knew nothing about.

Among the most important changes has been strengthening the understanding of special education staff about what their rights are, the pair agreed.

For example, when caseloads exceed recommended limits, a grievance can be filed. For NCPS, who had been lumped into the teacher evaluation system even though their jobs look nothing like teaching, evaluation tools have now been changed to reflect their professional roles through their professional organizations.

Many in the caucus were surprised to learn that bargaining prohibitions enacted by Republican lawmakers against teachers in recent years did not apply to NCPS, so placement, layoff and recall, discipline, and discharge can still be negotiated and grieved.

“It has been empowering to learn and inform our special education members about what their rights are and that they have a voice and a place to advocate through the union for their students and for the stability they need,” Yee said.

Read more #UnionStrong stories:

Strength in union takes many forms

Plan Points the Way to Solidarity, Strength, Success

Flint Teachers Unite for Contract Win

Local Unions Report Successful Bargains Across State

Union Members Stand Up in Emotional Board Testimony

Local Actions Combat Bullying Behavior at Board Meetings