Educators Engage in Racial Justice Movement: ‘I feel this moment very deeply’

By Brenda Ortega

MEA Voice Editor

For MEA member Lisa Watkins, the ongoing Black Lives Matter movement speaks to important and personal issues for her as a mother, grandmother, and associate preschool teacher in Ypsilanti—concerns that she believes every educator should seek to know and address.

“Educators are helping raise black lives,” said the mother of four and grandmother of nine. “We want our children to succeed and be able to make it in life, and some of that comes from us. We need to be educated about the issues, so we can help protect our babies.”

Yet Watkins has been unable to attend any local Black Lives Matter marches, rallies, or protests in recent weeks, because the 56-year-old is caught between two crises.

She wants to protest our nation’s long history of police brutality and racial bias. But she worries about her susceptibility to the deadly COVID-19 virus amid a global pandemic that also has disproportionately affected black Americans and other people of color.

“I have underlying health issues, and I really don’t go out of the house,” she said. “I follow the protests. I post them on my Facebook. I’m just concerned about my health; otherwise I’d probably be doing more.”

Black Lives Matter marches have been organized in cities large and small across Michigan in the past four weeks, following the horrific videotaped police killing of George Floyd in Minneapolis last month. Thousands of educators nationwide have joined in the current wave of activism.

Floyd’s murder at the hands of four officers recalls painful memories for Watkins of her children’s father being beaten by police before he died several years ago. She worries about the future for her grandchildren and students. “I love my babies,” the 24-year veteran educator says.

But Watkins also needs to care for herself. Her health took a turn for the worse in recent years as rising out-of-pocket costs forced her to drop health insurance, which meant she stopped taking medications and seeking care, which led to a series of damaging “silent” heart attacks.

As president of her local support staff union, Watkins helped negotiate recent contract changes that once again made health insurance affordable for her and others. She’s back on her medications, seeing a cardiologist, and feeling hopeful. “I love my MEA family,” she said.

Standing United

For 30 years MEA member Prasad Venugopal has been involved in peace, labor, and racial justice activism, but something feels different about this moment in the Black Lives Matter movement, he says.

“I feel hopeful about it, seeing how many young people are out there, how they are self-organizing, and how diverse that crowd is – particularly the number of white youth,” the 22-year associate professor of physics at University of Detroit Mercy said.

An immigrant to the U.S. from India three decades ago, Venugopal attended a rally in his community of Ferndale on May 31 and returned for another with his wife and two children on June 6.

“Young people see this contradiction between how much violence we’re inflicting on one side and at the same time how we’re neglecting the kind of social uplift programs that we need, such as health care and education. The system is broken down, and so they go on the streets.”

In 2011, Venugopal initiated a course at UDM on the intersection of science, technology, and race in America. The course examines how science recreates and reconstructs the concept of race, and how race and racial categories color research and practice in science and medicine.

Several days ago a former student emailed to say the class gave her confidence to sustain difficult conversations with friends and family during this period of national dialogue about over-policing of communities of color.

Venugopal’s first reaction was to cry; then he shared it with his wife. “These are emotional days, and I feel this moment very deeply,” he said.

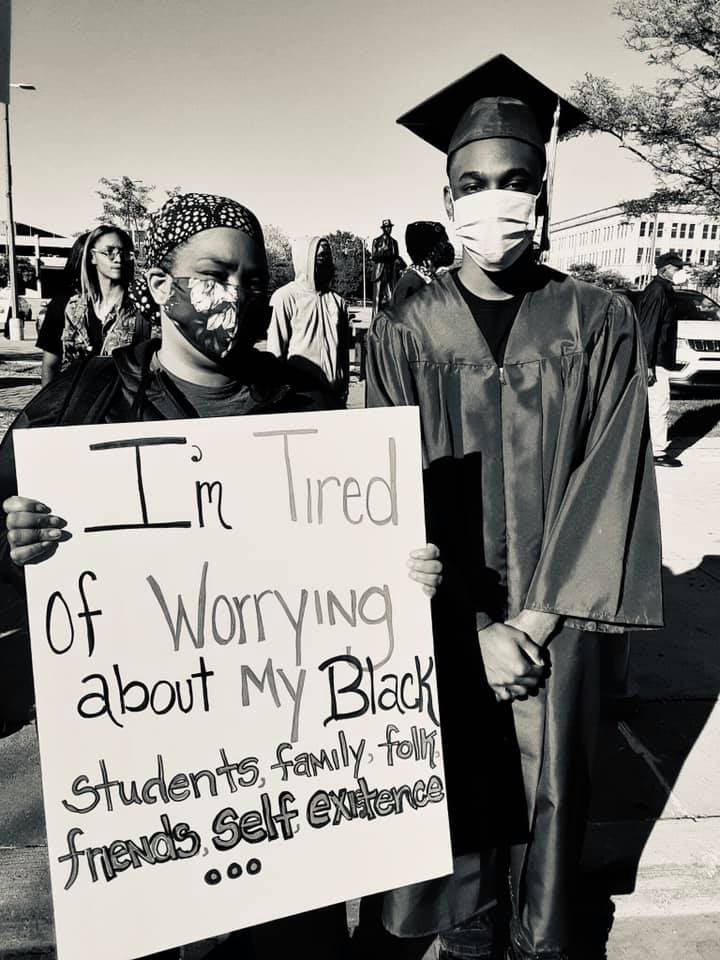

It’s important for students to see educators engaging around issues of racial injustice, says MEA member Aretha Bradley. As a black woman, she had been aware of the Black Lives Matter movement for many years, but recent events compelled her to learn more and take action.

A speech and language pathologist in Southfield Public Schools, Bradley attended a rally in Flint this month and connected more deeply with the Black Lives Matter message. “I think we all witnessed what happened in Minnesota, and it has awakened us as humans,” she said.

“We’re not only talking about law enforcement. It’s opened up racial dialogue that we are so hesitant to have but that has to happen. It has to happen. And hopefully that will lead to some positive outcomes across the whole diaspora of us as human beings.”

Of course all lives matter, Bradley says, but shining a light on ways in which black Americans suffer disparate treatment is meant to reveal how black lives historically haven’t mattered as much as others. “It’s time for the good people to stand up and say, ‘Enough is enough.’”

MEA member Mandy Clearwaters gave several of her elementary art students in Kalamazoo a chance to be heard after downtown business owners boarded up store fronts. The children made art on the plywood to communicate their ideas about racial equality, fairness and togetherness – and CBS News showed up to cover it.

One 11-year-old artist painted a scene of a black man enjoying a walk in nature with the message “We matter” alongside. Darek J. Roberts told CBS News that he wanted people to see “the beauty of black people and nature and how we can share it peacefully.”

Another young artist painted a half white and half black canvas over his spot on the plywood to center a black-white yin-yang with his messages straddling both colors: “Stand United” and “Can’t have white without black.”

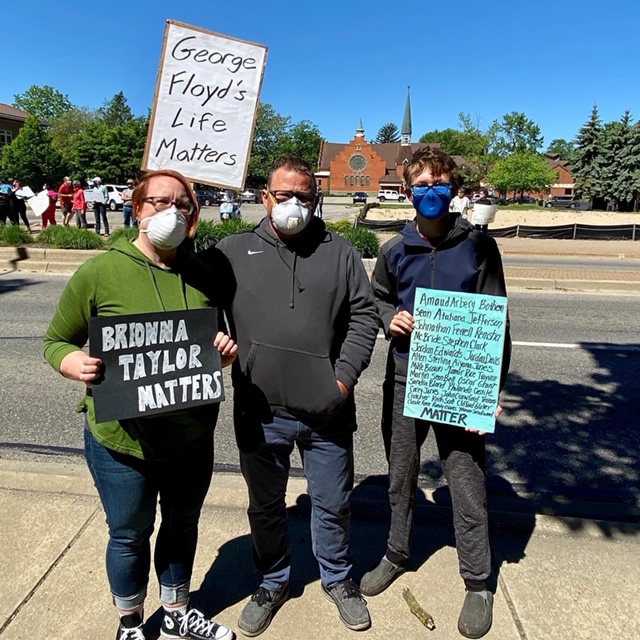

In Holland, another art teacher took a public stand for black lives. MEA member Dani Suhy, who teaches in Allendale, recently participated in her first protest of any kind – and went back for a second one – because she felt black people should not have to stand alone against injustice.

The protests were peaceful, diverse, unified, and integrated with faith leaders from the Holland community, she said: “It gave me hope to see so many show up and to have cars going by honking in support and pushing their fists out of windows in solidarity.”

For MEA member Jessyca Mathews, the participation of white educators in racial justice activism is crucial. An English teacher at Flint’s Carman Ainsworth High School, Mathews issued social media appeals for white colleagues to speak out for the sake of black students.

“They see and are processing your silence,” Mathews posted on Facebook. “They know what it translates to when you hide while black folks die… Step up. They need to know you are an ally.”

Mathews earned national recognition in 2017 for her innovative work to lift student voices in the aftermath of the Flint Water Crisis – a state governing scandal that the Michigan Civil Rights Commission blamed in part on “deeply embedded institutional, systemic, and historical racism.”

Mathews’ senior class on social justice activism teaches students how to research solutions to intransigent social problems and advocate for action. That’s why she was especially proud to participate in a June 12 march organized by recent Carman Ainsworth graduates, she said.

The Flint Youth Protest featured a downtown march and rally that drew about 300 people – including many local educators – and a list of demands which included the teaching of more black history in schools and the hiring of more black teachers and police officers.

“My children will change the world; I’m just here to love and guide them on their path,” Mathews said after she and others spoke at the rally. “Building my students’ voices and understanding that they matter in this world is what I’ve been put here to do.”

White Educators and Black Lives

White educators shouldn’t feel it’s their job to step in and save the day, said Vikki Kasperek, a special education teacher in Van Buren Public Schools who attended Black Lives Matter marches in Detroit and Romulus.

“The most important thing I have learned about this issue is that as a white person, it is my duty to support and to listen,” Kasperek said. “This is not my time to try to fix things but to wait for my marching orders – to do the work that needs to be done.”

Kasperek teaches elementary-age children with autism. “I worry police might kill my mostly non-verbal, mostly male, mostly of color students with autism due to their lack of training with people with neurological differences and their history of bias and use of force,” she said.

Kasperek has been approaching mayors in municipalities where she serves as a teacher to encourage them to sign the Mayors’ Pledge for police reform – sponsored by the My Brother’s Keeper Alliance, a nationwide initiative of the Obama Foundation.

“I am available to help however I am deployed,” Kasperek said.

Educators are “essential workers” in the fight against racism because of their unique role in society, says MEA member Robert Lurie, whose nearly 40-year career in Lansing’s Waverly Community Schools has focused on engaging and empowering students as involved global citizens.

In early June, Lurie organized a large contingent of educators from across mid-Michigan who joined a NAACP-sponsored Black Lives Matter march to the Capitol, where a rally was held. Our black and brown students need to see educators standing up on this issue, he said.

“We are calling on other actors in our society to do better, and we should. But we must do better, too, and this starts through listening, learning, changing and acting,” Lurie said.

MEA member Dana Blank is a white teacher who responded to Lurie’s call for action by showing up for the Lansing march and rally, because she wants to be one among many spurring society to do better.

“It was a call for change and a call for peace and a call to right things in the world,” she said. “I believe change will come when large numbers of people of different colors and ethnicities and orientations and body types and backgrounds come together to say we want to see change.”

Blank is also doing reading and viewing to better understand systemic racism so she can guide students in her English, writing, and speech classes in Ovid-Elsie Area Schools, a rural and predominantly white district.

Another action she plans to take in pursuit of racial justice is to work on political campaigns for candidates at the local and national levels, including presumptive Democratic nominee for president Joe Biden.

“I believe that, as president, Biden will do a much better job of working toward equality for all,” she said.

Three years ago, Blank and Lurie (among others) began an exchange program between her school district and the more diverse Waverly schools, where students speak numerous languages, represent different cultures, and come from many racial and ethnic backgrounds.

Engaging with and learning about big societal problems is a lifelong pursuit, Blank says: “It makes me want to do more, be better, teach what matters, and be a part of what’s going on.”

Beyond the Marches

Educators should understand and teach historical factors that contribute to institutional racism which still exists today, said Maurice Telesford, a chemistry and physics teacher at Ferndale High School and president of his local education association.

But educators can’t tackle such huge societal problems without training and resources, he added. “I’m a black man, and I’m not trained to work in this space. It’s a very sensitive, uncomfortable space, so I think it needs to be pinned more on the education system.”

Recruiting more educators of color would bring a wider array of voices to the table and encourage more diverse perspectives to be represented. As of now, “The pipeline just doesn’t exist, and I think that change has to come from the state or federal level,” Telesford said.

Other big problems – such as under-representation of students of color in Honors and Advanced Placement classes – can be tackled at the building level as is happening at his school, he said.

In Ferndale, more than 85 percent of students in Honors and AP classes are white, although the student body is 60 percent black. The district brought in an outside firm to guide discussions about how to address the problem, Telesford said.

The narrow goal of the equity work has been to increase participation in those courses by students of color, but ancillary goals of encouraging and improving the conversation about race have also been addressed, he said.

“I’ve been teaching at the school for 11 years, and we’ve never in my time there had some of the conversations we’re having now about white privilege, about inclusivity, about reasons students choose to take more challenging classes that have nothing to do with their ability, about the role of parents and culture.”

MEA member Wendy Winston is spending time this summer reading, learning, and reflecting on those same types of issues. The middle school math teacher in Grand Rapids is not able to participate in marches out of concern for family members with underlying health issues.

Right now, she’s reading Rethinking Mathematics: Teaching Social Justice by the Numbers, a book she picked up at last summer’s NEA Conference on Racial and Social Justice.

Last summer, she read These Kids are Out of Control: Why We Must Reimagine ‘Classroom Management’ for Equity. In February, she attended a Grand Rapids NAACP screening of the documentary, Pushout: The Criminalization of Black Girls in Schools.

“These are hard times,” Winston said. “I find it especially difficult because I can’t rally or advocate the way I normally would!”

In addition to continuing to read and learn, Winston has posted messages on social media in support of the Black Lives Matter movement. One post in particular received some special attention.

When Winston shared a picture of herself wearing a t-shirt emblazoned with the words “THIS TEACHER HAS HAD #ENOUGH,” a former student shared the photo and tagged Winston with a tribute to say, “This lady changed my life for the better.”

“She’s one of the big reasons why I am an engineer and she’s one of the big reasons why I’m successful,” wrote Shalah Dean Thomas. “I HATED math. I struggled, staying up all night with my mommy trying to understand it.

“In 7th grade, Mrs. Winston promised me if I take her Math 101 class instead of art, gym, music etc. with my friends, I would understand math and love it. Maybe a week in her class, I understood math and loved it. I had the highest scores in my math classes and I was the only African American to earn the mathematician award at our 8th grade graduation.”

Thomas now holds a Bachelor of Science degree in Computer Engineering, a Master of Science in Engineering Management, and she’s pursuing a PhD in Industrial Engineering. She works as a systems engineer at Lockheed Martin in Orlando.

“Thank you so much Mrs. Winston, you changed my life for the better and I’m forever grateful,” Thomas concluded.

MEA as a Social Justice Advocate

For other MEA members who would like to learn more by reading and discussing a book on racial justice, a digital summer book study with SCECH credits is in the works through MEA’s Center for Leadership and Learning.

Members interested in the book study, slated to start in the beginning of August, should email Director Kia Hagens at khagens@mea.org. Members can also join the MEA Center for Leadership & Learning Facebook group to keep up on the latest professional development offerings.

MEA’s leadership is committed to exploring and addressing systemic racism, including how it has existed in unionism and public schools, said MEA President Paula Herbart, who participated in a recent MEA webinar on the subject organized by Aspiring Educators of Michigan (AEM).

“We are committed to working hard and to asking people of color what they need from us and how they can best lead our organization in this work,” Herbart told attendees at the virtual “Educators for Racial Justice” gathering, held via Zoom and livestreamed on YouTube.

AEM member questions guided the discussion, which was led by two MEA member teachers – Anthony Barnes from Kalamazoo and Dr. Kecia Waddell from Utica.

The one-hour session covered a broad array of topics related to racial justice, such as white privilege and how to use it to benefit others, the differences between systemic and personal racism, and the difference between being a non-racist and an anti-racist.

“The difference between not racist and anti-racist is action,” said Barnes, a Kalamazoo special education teacher and early career educator. “It’s about using your privilege to make a difference for someone else.”

Barnes said he believes it’s important to live his ideals at all times – not just when he’s within the walls of his school. And he incorporates lessons about diversity, inclusion, and social justice for all in the curriculum but also as it arises in current events and in the community.

“Use teachable moments, but first you have to check your own bias,” Barnes said. “And if you think you don’t have any bias, you’re lying to yourself. Let’s be honest—everyone has their own biases.”

Classroom conversations about race can be difficult, but they are essential in building respect and understanding once students feel comfortable sharing their views, said Waddell, a longtime high school English teacher and the only black teacher in her building.

People are going to be uncomfortable talking about race, because the issue is so big and goes beyond the individuals having the conversation. People have to understand – it’s not personal; it’s systemic, Waddell said.

“I don’t know where we imagine there is this comfortable space in life,” Waddell said. “Where there is struggle, on the other side of that there is triumph. There’s no testimony without the test.”

The conversation also included classroom tips on how to diversify curriculum, how to be more inclusive, how to lead classroom discussions, and more. Watch the webinar.

Making Your Voice Heard

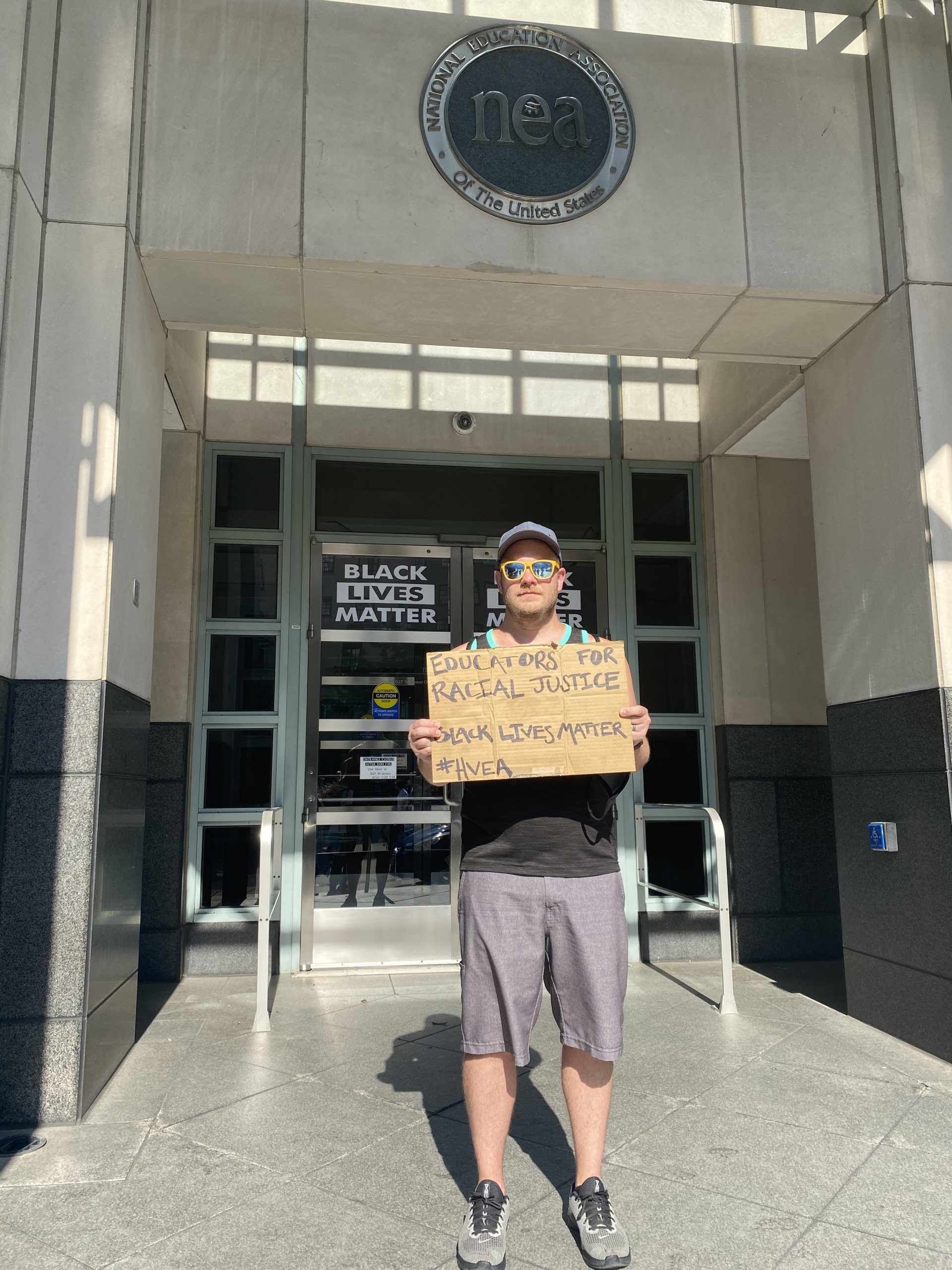

MEA member Nick Peruski didn’t always think of himself as “the protesting type,” but increasingly he’s found himself moved to “make my voice heard and fight for the rights of others” over the past few years, he said.

On an impulse, he and a friend drove to Washington, D.C., earlier this month for a Black Lives Matter march and rally involving an estimated 200,000 people, which he described as “one of the most inspiring events that I have ever attended.”

“Almost every single protester wore a mask, even in the 90-degree heat, which showed their care for each other,” he said. “It was refreshing to be in such a large group of people but feel like we all had each other’s backs.”

The vice-president of the Huron Valley Education Association, Peruski was honored with a prestigious national Milken Award in December. “As an educator of our youth and a marginalized gay male, I see standing up to social injustice as my moral obligation,” he said.

“Everyone deserves equal access to opportunity and respect, and I will fight to ensure that happens however I am able to do so. We are all humans, deserving of love, and we need to remember that there is more that unites us than divides us.”

I think it’s great to stand up for black lives (all lives) all the time, not just when it’s popular. I think it’s also important to mention there is a difference between peaceful protest, and rioting. BLM movement has been drawn into riots and is a part of the destruction of property. Also as an educator, and the wife of a police officer, I am saddened to see the hate being spewed toward the great men and women of police departments around the country. The police are not the enemy. The real enemy is the political forces using black people and this movement to get votes. For them, this is not just about black lives. It’s about political power.

Well said! Amen🙏.