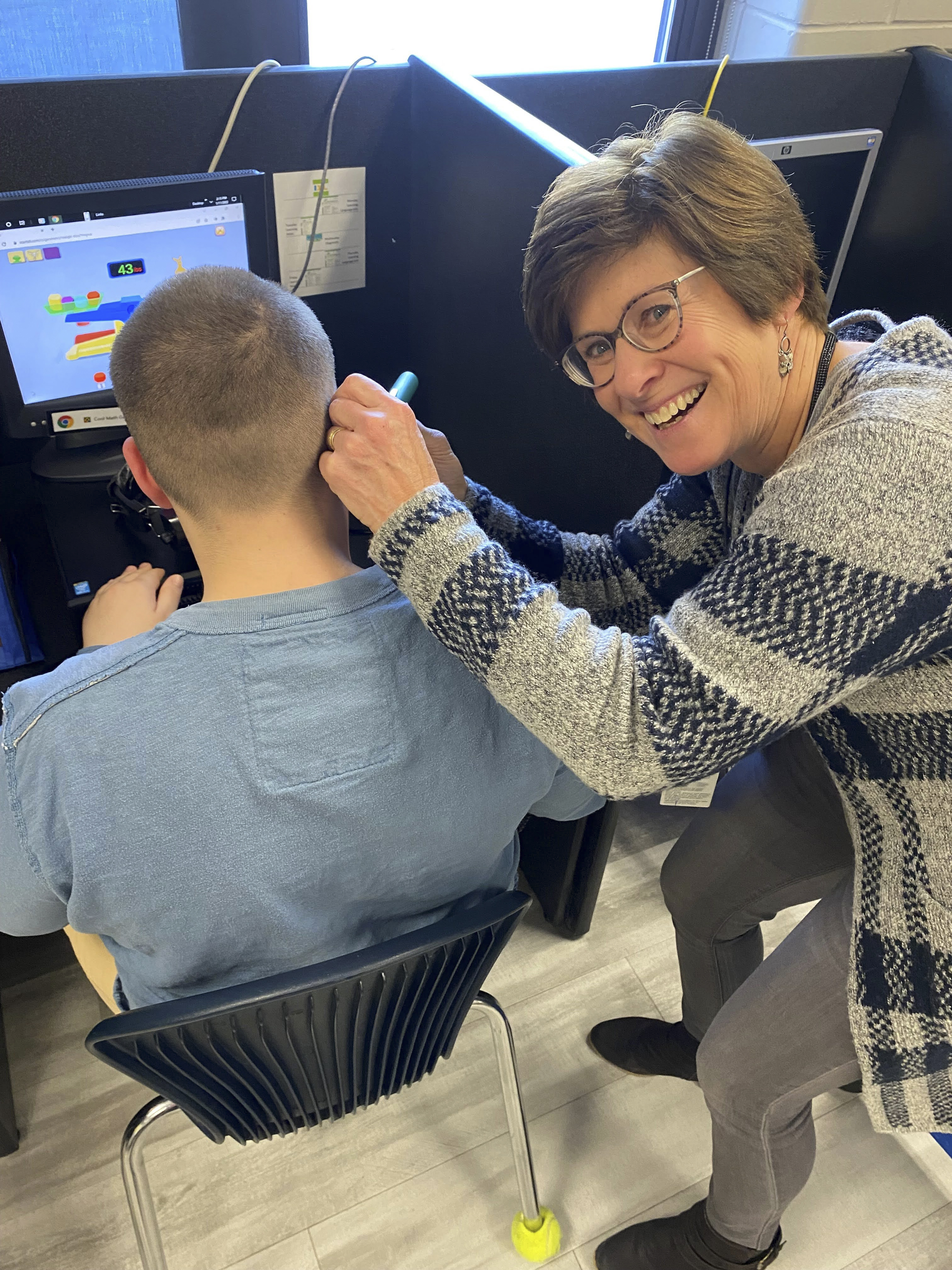

School Nurse: ‘We treat the whole child’

If a student comes to school nurse Phyllis Yoder with a stomachache three days out of the week, the MEA member will consider a number of causes. Perhaps the child is hungry because of food insecurity in his life. Possibly a medical condition is at the root of the problem.

If a student comes to school nurse Phyllis Yoder with a stomachache three days out of the week, the MEA member will consider a number of causes. Perhaps the child is hungry because of food insecurity in his life. Possibly a medical condition is at the root of the problem.

Or maybe there’s a behavioral health cause: anxiety, bullying, violence?

“School nurses treat the whole child,” Yoder said. “That child has interacting dimensions: cognitive, physical, mental, social-emotional. Those all work together, and we address them all.”

In addition to the typical role of a school nurse—advocating for students who are well-nourished, healthy, and ready to learn—Yoder coordinates her school’s medical response team and guides parents of young children through the process of determining if their child has special needs.

For the past 20 years, she has worked at Huron Intermediate School District in Bad Axe in a center-based special education school and preschool, serving students from birth to 26. She dispenses medications, directs care for medically fragile students, and coordinates wellness activities.

Nurses work in a vital capacity—especially given the fact that 1 in 4 students has a chronic illness such as asthma or diabetes—but a shortage of school nurses nationally means just 40% of schools have a full-time registered nurse on staff.

That leaves school employees such as secretaries and paraeducators to handle medical needs—for example, inhalers and insulin pumps—with the potential for problems or reactions they’re not trained to assess or address, Yoder said.

In Michigan numbers of school nurses are not well-tracked, so no official student-nurse ratio is tallied. In addition, no certification requirements or universal standards exist in Michigan governing a nurse who works in a school setting, which some are working to tighten.

In Michigan numbers of school nurses are not well-tracked, so no official student-nurse ratio is tallied. In addition, no certification requirements or universal standards exist in Michigan governing a nurse who works in a school setting, which some are working to tighten.

The COVID pandemic and associated health requirements have brought the need for and importance of school nurses into the light, Yoder said. “It’s Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs. If students don’t have basic needs met, if they aren’t feeling secure, they’re not going to be able to learn.”

Meanwhile, an already serious nursing shortage is about to explode, she said. Baby boomers are ready to retire, and the demands of contact tracing and other pandemic workloads have burned out many others, Yoder said. “Who can replace these retiring and burnt-out nurses? We don’t have adequate sources of nurses in general to be able to staff our schools.”

Part of the problem is a pipeline issue seen across the U.S.: Too few nursing instructors limits the number of slots available in college and university nursing programs. However, another issue is that many school districts overlook school nurses for other types of health professionals.

“Nurses are trained to spot the physical issues, the mental health issues, the behavioral issues,” Yoder said. “We need teams of professionals to treat the whole child and give every student the greatest chance at success.”

Read more about mental health needs and solutions from the experts on the ground:

Meeting the Mental Health Challenge

School Counselors Confront Crisis