Tavia Redmond: ‘Let me tell you about tired’

Love ultimately led MEA member Tavia Redmond to don her teacher’s cape 28 years ago.

Since then, she’s faced tough challenges with grit and patience—mostly in her hometown of Romulus, the Downriver suburb that is home to Detroit Metropolitan Airport. But nothing compares to this year’s struggles, she says. “This right here is a whole new ballgame.”

Redmond never envisioned being asked to teach a split class in which half of her third graders are physically present in the room—masked and unable to share supplies or mingle with friends—and half are watching from home through a computer screen.

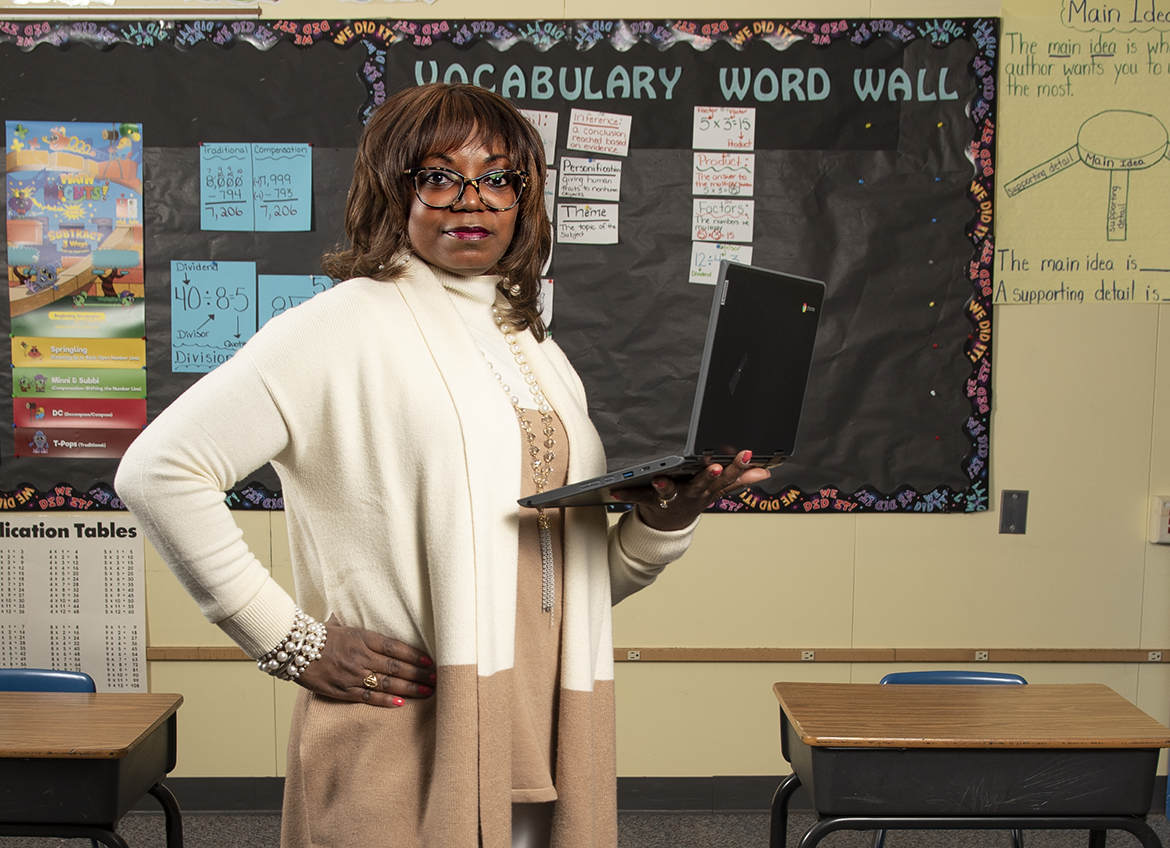

It’s hard to know even where to stand so both in-person and remote kids can see and hear her speaking through the mask. She’s taken to carrying the Chromebook with her. “It is very difficult, and I don’t think people who are not in the classroom see what we’re going through.”

Until March 10—the one-year anniversary of Michigan’s first confirmed COVID-19 case—all district students had been learning remotely since last spring. When some returned to the building for the first time that day, Redmond entered a new phase of teaching—hybrid—and discovered new levels of exhaustion.

“Let me tell you about tired. I came home from work and went to bed, woke and ate something at 6:30, took a shower and went back to bed, and woke at 6 in the morning.”

It’s a big task to get the 12 youngsters in the room to understand why they can’t do so many simple things they used to enjoy, like sharing a box of markers or holding hands with a friend.

“They get that they have to wear a mask, but they want to do those things they’ve always done in school, and I have to say ‘No, you can’t do that. You can’t share your markers. No, you can’t sit together and color. You can’t give her your yogurt that you don’t want.’

“I snapped at a girl yesterday because she had some grapes and another student said, ‘Oh let me have one,’ and she went to give her a grape, and I said ‘No!’ And then I was like, ‘I am so sorry. Please forgive me.’ And with all the kids on virtual saying, ‘What’s going on?’ I said, ‘Honey, you can’t. Please, just don’t.’”

It breaks Redmond’s heart, she says. “Those things we were taught about cooperative learning, working together in groups, sharing, it’s gone. Out the window.”

All who returned to in-person learning look forward to recess time, including Redmond. “When we went out on the playground for the first time, and the weather was so nice, it brought me joy to see them getting fresh air, running around, chasing, playing tag and shouting, ‘Who’s it?’”

For many reasons, this year has felt “discombobulated” to a veteran educator who still remembers in sixth grade devouring a Scholastic News story of Marva Collins, a celebrated Chicago educator who became the subject of a TV movie starring Cicely Tyson.

Everything about virtual teaching last fall was unfamiliar—from digital strategies to scanning documents, navigating Google classroom, and mastering a learning platform all at once. “You spend hours trying to figure out every little thing, and you finally start to get in the groove and the next thing pops up,” she said. “I can’t keep up with everything.”

One big issue for Redmond, like other K-3 teachers, has been completing all of the mandated testing while her 31 students were attending online for much of the year.

Under Michigan’s third-grade reading law, K-3 educators must gauge students’ reading levels three times a year and use scores to develop an Individualized Reading Improvement Plan (IRIP) with interventions—which must be tracked and reported—for any who don’t meet a benchmark.

Her district uses an online tool—the NWEA—and a labor-intensive one-on-one assessment known as the DRA, Developmental Reading Assessment. Some results have been inconsistent.

She tried to have the students remain on-screen while taking the online test, but computer glitches and internet issues forced her to let them leave to complete it. Some students she noted reading far below grade level on the DRA somehow scored high on the NWEA.

The discrepancies made it hard to design interventions for the IRIPs and to communicate a plan for parents to work on at home, as required under the law. “I could use information from last year to help me gauge where they were going to go, but it was a tough call,” she said.

One good that came from parents sitting by their children to start remote learning last fall was having some see firsthand their child’s reading struggles. For example, when she asked students to find a word on the screen, some parents were surprised their child couldn’t find it.

“I was able to see some changes in some of the kids whose parents started working with them, because they realized, ‘Whoa, my daughter can’t read like I thought she could.’”

Redmond found a rhythm with all-virtual teaching as she discovered students’ digital attention span. She added breaks and GoNoodle movement and kept her video on at lunch for social time. She started optional Fun Friday to let kids talk or play games such as Simon Says. It was amazing to just watch and listen, she said.

“At times they weren’t talking, but they stayed for the fact they could see one of their classmates coloring and they could color, too. They would go, ‘Look at this picture—look what I did!’ Or they would play and say, ‘Did you see me?’ Or ‘Watch me make this shot!’ Then a girl would maybe start playing with her dolls, and the boys would shout, ‘Lemme go get my game!’”

As students returned, she also discovered the limits of in-person school when a melancholy girl shared a sad story about her puppy. “My instinct is to put my arm around the child, and I had to catch myself and remember I can’t. I can’t hug. It’s sad, really sad.”

Redmond is able to keep going by tapping wellsprings of strength. “I have been praying, and I have been walking. When my thoughts keep going left and right, that is my outlet—just praying and walking, writing in a journal, enjoying nature, because it helps me to get away for a while.”

Read more stories from the series, “What it’s Like: COVID Vignettes”:

Karen Moore: secretary with a purpose

Karen Christian: COVID ICU survivor

Jacob Oaster: leader, teacher, innovator

Amy Quiñones: Charting New Waters

Union Presidents Lead through Unprecendented Crisis

Jill Wheeler: On Books, Kids, and ESP

Gary Mishica: His Work is Hobby, Joy, Passion

Demetrius Wilson: ‘We’ve made it work’

Shana Barnum: ‘It’s heart-wrenching’

Claudia Rodgers: Committed to her Work

Danya Stump: Building Preschool Potential

Rachel Neiwiada: Honored on National TV

Gillian Lafrate: Student Teaching With a Twist (or two)

Jaycob Yang: Finding a Way in the First Year

Julie Ingison: Bus Driver Weaves Love into Job

Chris DeFraia: Sharing a Rich Resource