Union Presidents Lead through Unprecedented Crisis

What’s it like to be a local union president in the age of COVID?

In this story, we talk with three local leaders in Macomb County—an urban hotspot in northern metro Detroit—who have employed every tool at their disposal to unite members and guide collective action through the most challenging circumstances in living memory.

As in districts across the state, local decision-making processes require MEA locals to determine and advocate for what’s best for their

members and their community.

By Brenda Ortega

MEA Voice Editor

From what she’s seen, L’Anse Creuse Education Association President Kathy Parmentier says every local union leader like her has faced daunting challenges this school year unlike anything before. “It’s one thing after another,” she says.

“We solve one problem and another one comes up, and then we solve that problem and something else happens. It’s just a never-ending list of issues and concerns that we’re trying to get addressed.”

Parmentier teaches biology in the 10,000-student district which began the school year with five-days-a-week full face-to-face learning with a virtual option chosen by about 30 percent of families.

At various times in this tumultuous school year, communities across most every Michigan county have watched COVID-19 infections, hospitalizations, and deaths make a steep ascent—and with them the fears, illnesses, and troubles of school employees.

“There was a time when I would get constant phone calls from teachers saying, ‘I’m crying every day,’” Parmentier said. “They’re concerned about their own safety. Some have immune-compromised children or older family members, and they’re afraid of being that carrier who transmits something. They’re concerned about their students’ safety. And they have this huge extra workload to keep up with. It has been very, very challenging for all of my teachers.”

The biggest issue for classroom educators in her district—class sizes—has also been hardest to solve, despite ongoing communication between the union and administration. Talks led to the hiring of a dozen additional teachers to keep class sizes down around 20. That allowed for some physical distancing, though not the recommended six feet.

Repeated surveys of the LCEA membership revealed 60 percent were OK with 20 kids per room, but 75 percent feared overcrowding if virtual-only students returned to classrooms at the start of a new semester in the middle of a high-virus-transmission winter.

To pull together members of differing viewpoints, a crisis team was formed to build consensus around safety priorities to focus on ways to publicly demonstrate solidarity.

Regular building meetings and general membership meetings have been held to keep people apprised of what the leadership is doing, “because I’m always talking with the district and working to solve problems, but they don’t always know what’s happening.”

Many members have stepped up to email school board members and speak at school board meetings. Tensions have formed as some board members and parents have pressed for buildings to reopen without addressing the needs of the adults who staff them, Parmentier said.

Pushing for face-to-face instruction at times of high community spread of the virus means pinging back and forth between in-person and virtual for students and staff who either contract it or must quarantine because of exposure—raising stress levels and interfering with learning.

“And not just teachers—we had one day that a building had no food service workers because everyone had gotten either sick or exposed. Secretaries, administrators, custodians, tons of people… at one point, we had 300 staff members out.”

Heading into the holiday break, nearly 85 percent of her members surveyed said they felt unsupported by the school board.

“On a positive note, the board did approve a $500 thank you payment to all staff. But people feel that’s a Band-Aid when they see board members who aren’t paying attention, who are talking to their neighbor when someone is in front of them expressing concerns, literally in tears.”

A ‘Family’ Divided

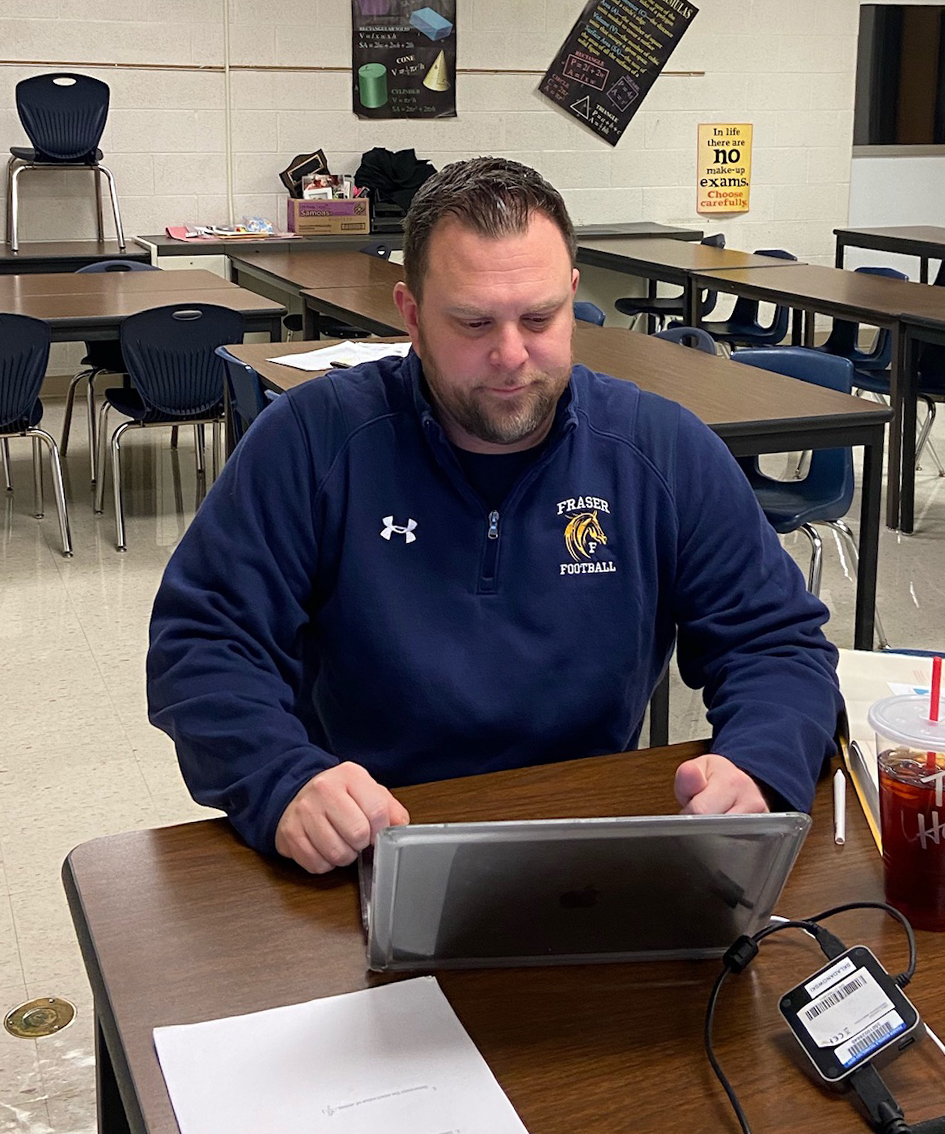

The disagreements have also divided folks in nearby Fraser, where union president Jon Skladanowski grew up and returned to more than 20 years ago to spend his career teaching math and coaching football because of its tight-knit small-town feel.

The vast majority of members in the FEA want to run a hybrid system that rotates smaller groups of students into buildings at a time, but the school board has been determined to operate a full-time face-to-face schedule.

“We don’t feel like the Fraser family whatsoever,” he said. “I was interviewed by Channel 4, and I said, ‘You can believe whatever you want. You don’t want to listen to facts, don’t listen to facts. But can’t you err on the side of caution for your fellow people?’”

Last summer the district approved a plan to operate remotely through Jan. 25, after which small groups of students would return. However, under community pressure the board abruptly reopened K-8 buildings to all comers on Dec. 9— amid dramatically rising winter case numbers that prompted a statewide “pause” for high schools where virus transmission rates were higher.

After four days, sick students had exposed dozens of teachers and classmates, a principal, and secretary, all of whom went into quarantine Skladanowski said. Heading into the holiday break, his preschool daughter was forced to isolate from exposure to a COVID-positive teacher.

Yawning statewide shortages of substitute teachers hamper efforts to fill absences. “It’s unsustainable,” he said. “Our custodians, our administration, our teachers are working their tails off to make this work.”

The divide has been difficult to bridge, because discussions inevitably break down, he added.

“I’ve always had a great relationship with the board and with central administration, but it’s to the point where we can’t even discuss this because there’s no changing their mind. It doesn’t seem to matter if everyone gets (COVID)— they would still try and open up the school.”

An increasingly unhappy membership began crisis activities in December to apply pressure on the board—wearing red, walking in together, walking out together, pushing their message on social media and in public comment periods at board meetings.

A general membership meeting was held around the same time to explore options with the requested help of MEA UniServ, Legal, and Executive staff, including President Paula Herbart, who spent her career teaching vocal music at Fraser. “It’s easy for me to say what’s best to do, but that has to come from you, knowing all the factors,” Herbart told those assembled in the virtual space. “We’ll back you up whatever you do, but are you willing to possibly lose your jobs? You have to think about that, and it’s hard. You should never have to be in this position.”

The group took a job action vote, but for now members are documenting safety concerns.

“We’re not against face-to-face instruction, and we’re trying to make it work,” Skladanowski said. “But at some point when there’s too much virus going around, we have to admit that it’s just not going to work.”

Meanwhile, Skladanowski expects to see more staff members retire, quit, or escape to more employee-friendly districts as some already have done.

“I’ve stayed in Fraser my whole life because it’s a community that always looks out for each other—or that’s the way we used to be,” he said.

Listening to Lead

One problem in navigating such an epic crisis is that school board members generally do not understand the intricacies of how schools and teachers operate, said Jamie Pietron, president of the union in Anchor Bay School District, which straddles southern St. Clair and northeastern Macomb counties.

“They don’t understand how disruptive the back-and-forth is to staff and kids and learning. You’re virtual, you’re not. You’re quarantined, you’re back. Teach these students, now those students. Do this, now that. Everyone is working harder than ever, and it’s exhausting and frustrating.”

After the district announced plans to start the school year in full face-to-face mode, about 30 teachers requested leaves of absence for medical concerns and issues, Pietron said. About 20 percent of the district’s 5,900 students indicated an interest in virtual learning.

She and local leaders shared concerns about a lack of thorough protocols and protective equipment with area news media.

Eventually district officials relented and began the year remotely for one month to prepare safety plans and gather supplies, she said. The public backlash was swift for Pietron, a special education teacher who says the nastiness she experienced was “very difficult” even though she’s a “tough girl.”

“I’ve given 20 years of my life to this district and to these kids, and it’s disheartening,” she said.

Educators are grieving the loss of normalcy and connection with kids at the same time they’re having to learn all-new ways of delivering instruction and even documenting attendance. Pietron conducts nearly weekly surveys that include open-ended questions to keep in touch with needs.

The crisis has unified her membership, and a greater number of them now step forward to email and speak to board members to be heard and press for change. The five-year president has tried to show them she will always be there to help.

“People want to know we’re in this together and someone is listening and advocating,” she added. “It’s that group mentality. It’s nice to know these are your people.”

Local leaders and MEA staff are using every tool in their toolkit during this crisis, including strategies old (job action/school board pressure) and new (Michigan Occupational Safety and Health Administration complaints). Last month, South Lake Public Schools in Macomb County was cited and fined $9,800 by the state for COVID-19 safety violations.

Where districts are not adequately addressing safety issues related to spread of the novel coronavirus, MEA is working with members to file complaints with MIOSHA—either individually or on behalf of groups of employees. For assistance, contact your local UniServ office (mea.org/uniserv) or visit MIOSHA’s COVID Workplace Safety page at michigan.gov/covidworkplacesafety.

Read more stories from the series, “What it’s Like: COVID Vignettes”:

Karen Moore: secretary with a purpose

Karen Christian: COVID ICU survivor

Jacob Oaster: leader, teacher, innovator

Amy Quiñones: Charting New Waters

COVID-19 Q&A with Paula Herbart

Jill Wheeler: On Books, Kids, and ESP

Gary Mishica: His Work is Hobby, Joy, Passion

Demetrius Wilson: ‘We’ve made it work’

Shana Barnum: ‘It’s heart-wrenching’

Claudia Rodgers: Committed to her Work

Danya Stump: Building Preschool Potential

Rachel Neiwiada: Honored on National TV

Tavia Redmond: ‘Let me tell you about tired’

Gillian Lafrate: Student Teaching With a Twist (or two)

Jaycob Yang: Finding a Way in the First Year

Julie Ingison: Bus Driver Weaves Love into Job

Chris DeFraia: Sharing a Rich Resource

Eric Hudson: Playing a Part to Beat the Virus

Sally Purchase: ‘Art is a little bit like a relief’